Review by Rudy Vega •

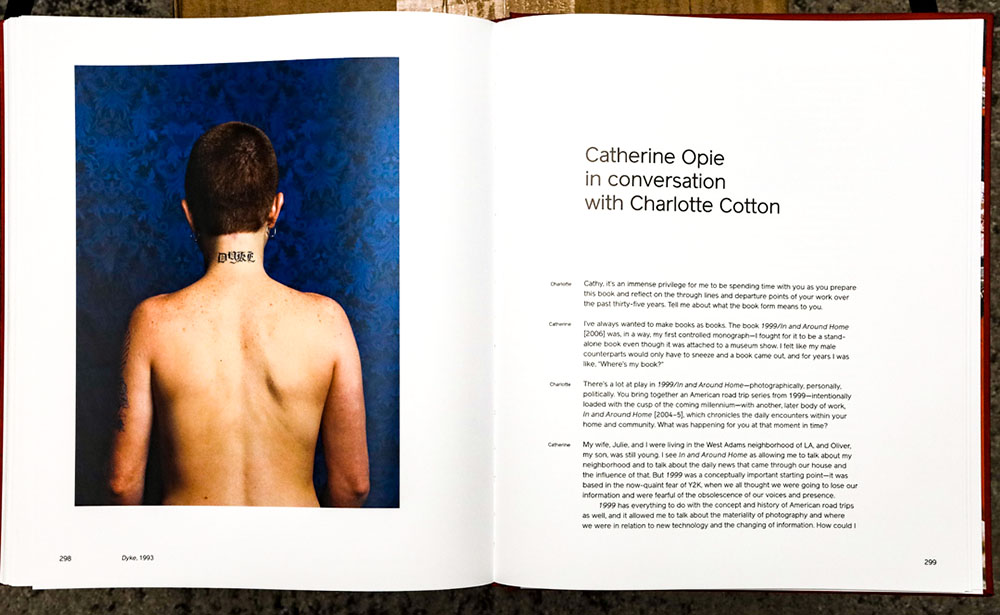

Catherine Opie epitomizes what it means to be a prolific artist as Phaidon’s recent release, Catherine Opie aptly showcases. It is a handsome hardcover book of 338 pages of which 300 are of images, including 6 gatefolds. Additionally, there is an introductory essay, and three additional essays serving as lead-ins to the chapters, and distinguished by their blueish gray color. The book closes with an interview with the artist by Charlotte Cotton. Taken together the material compiled in Catherine Opie, provides the most comprehensive overview of her work to date.

To the uninitiated or the casual follower, Phaidon’s Catherine Opie presents an opportunity to examine, study and admire her personal engagement with photography in one volume. And for those who have followed her career, Catherine Opie is an opportunity to revisit past projects, discover new insights, while also being introduced to previously unseen work.

With such prodigious output, one imagines the challenge to order Opie’s photography to be equal in ambition to the work itself. Opie collaborates in the process of compiling and organizing the collection, eschewing the traditional, if not favored, form of presentation–chronological order. Instead, Catherine Opie is structured around a thematic template consisting of three sections: People, Place and Politics. One notices the arrangement is not strict as images find slippage, occupying the potential for multiple readings while denying easy classification. In doing so, the reader of Catherine Opie, is free to make connections between images among the categories to discover how formal, technical and conceptual concerns inform a given project. The end result invites the viewer to a casual perusal of the book, inviting multiple viewings as the images suggest more than what an initial look provides.

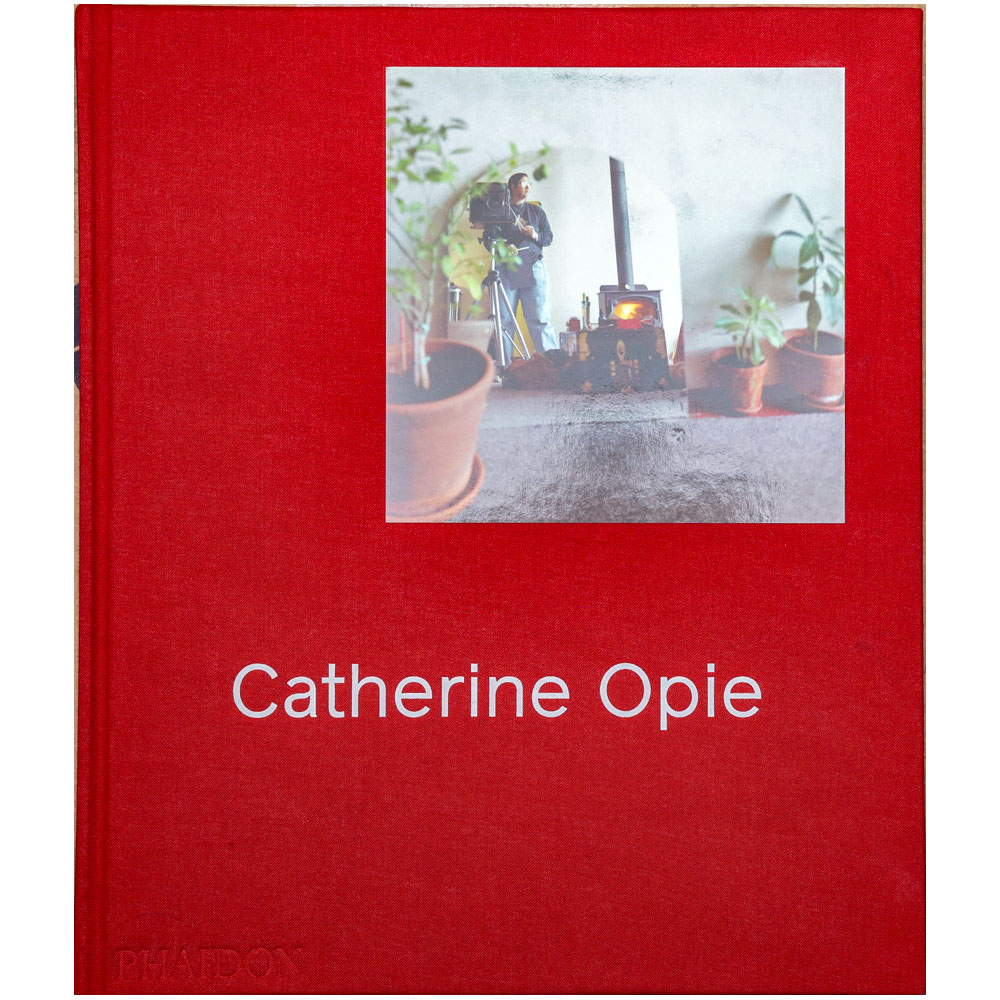

The front cover of Catherine Opie has a self-portrait of the artist at work. The back cover has a similar self-portrait. In the cover image, Opie is holding the darkslide from her 8×10 view camera in one hand and the shutter release in the other while she looks off camera to one side. We know this because the composition is formed within the reflection of a mirror. The photo placed on the back cover, has her redirecting her gaze back at the mirror, and by extension at us, thus acknowledging the self referentiality of the process. The set-up perfectly encapsulates the idea of the artist as maker and subject at the same time. On the surface, it may seem a simple gesture, but it is slyly executed– playful, while opening a dialogue with photography itself. The photographs in between the two covers reveal the dialogues Opie has had with photography for the better part of forty years.

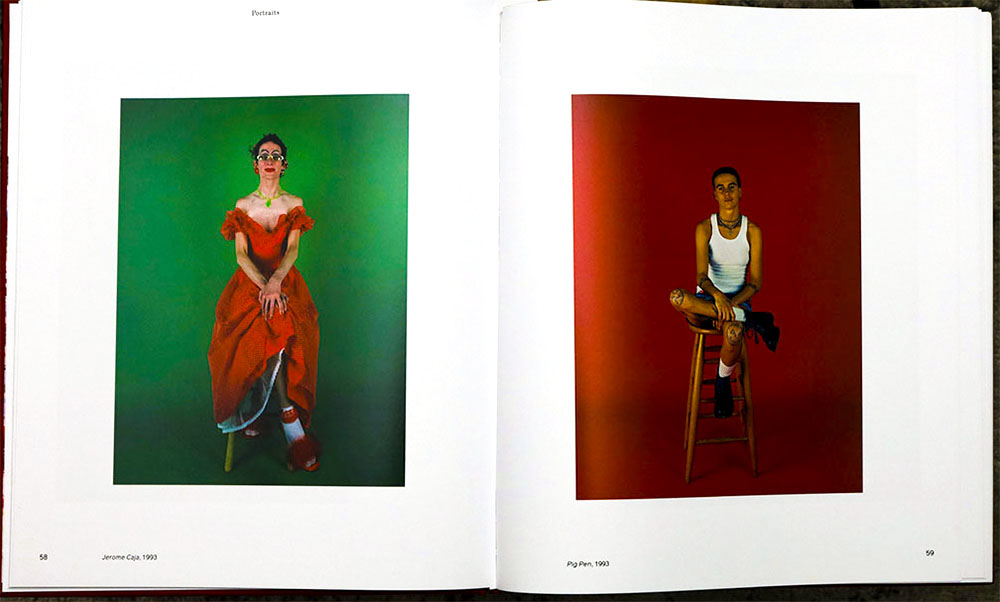

The compilation of photographs begins in earnest on page thirty-one of what is, People. Located top center is a heading citing the project/series from which the photograph belongs to. At the bottom left, there is a caption citing the title and the date the image was produced. This will serve as the template for how the images are notated.

The first image is a small black and white self-portrait from 1970 of a young Catherine Opie. In it, she is posing in the yard of her family home while flexing her muscles. It is an apt introduction that soon evinces her journey to a life engaged with photography. The closing image of People is also a self-portrait from 2009, titled self-portrait/red corner. In between the two self-portraits reveal a diverse methodology. This allows her to tailor an approach to meet the objectives of a given portrait(s), while at the same time, experimenting with the very idea of portraiture.

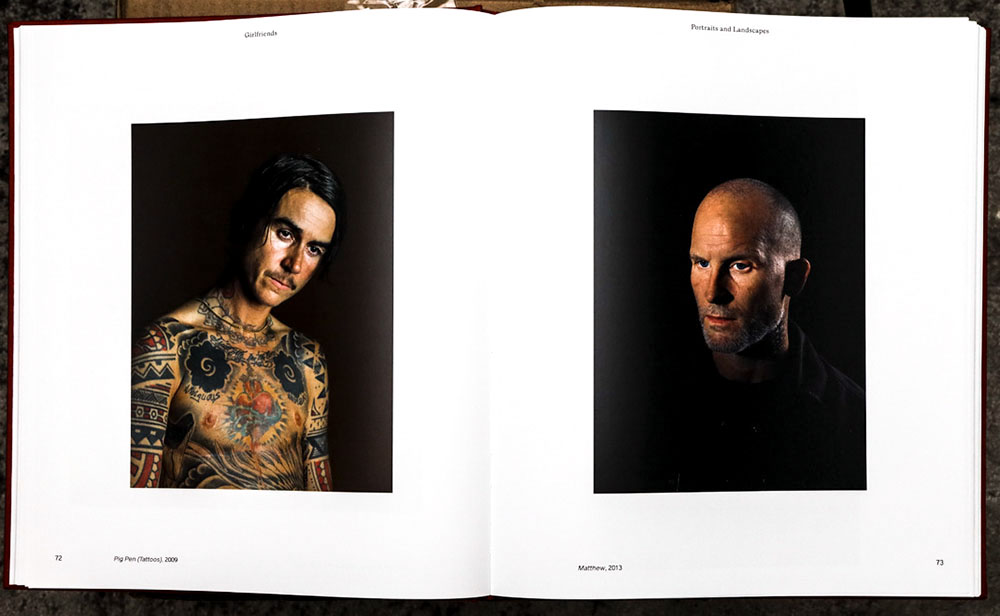

People are presented in black and white and in color. Some are in a studio environment with controlled lighting, others on location with available light. Aspect ratios differ according to the camera’s format. Compositions reside within rectangles, squares or cameos. Some portraits are full length, while others are tightly cropped, and still others are focused on body parts. A few dispense completely with one’s physical likeness to let their personal belongings function as their portrait. One feature of Opie’s portraits clearly in evidence is the rapport she establishes with her subjects. It is uncanny how her portraits evoke calmness, comfort and a willingness to share their personal likeness. It speaks to Opie’s direct participation with the communities portrayed but also to her dedication to the art of portraiture. Opie perfectly blends technical considerations with people skills to produce revealing and compelling portraits.

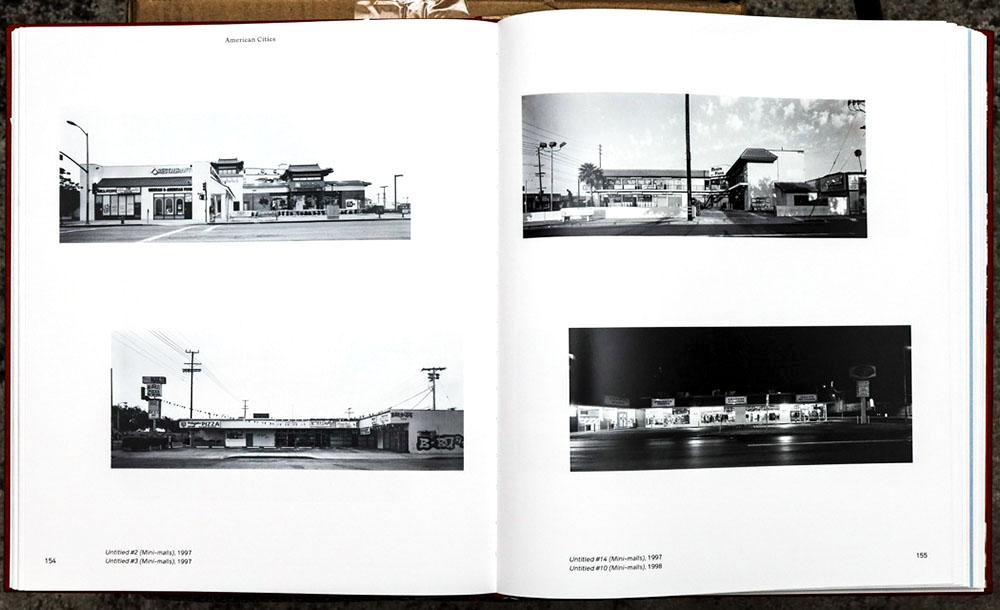

Catherine Opie makes visible an artist who thrives on diversity as the second theme: Placedemonstrates. Rather than organize Place as physical spaces, Opie explores sites as states of mind or as in the case of Icehouses, Surfers and Twelve Miles to the Horizon–the sublime. These projects stay beholden to the idea of communities, but they also explore the interiority of mind. Opie’s camera documents solitude, waiting and patience–hallmarks of the activities taken place in these environments. Whether it’s the ocean and sky demarcating the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean (while transiting via cargo ship from Korea to the US.), the marine layer shrouding the surfers with a blanket of June gloom, or the whiteout conditions on frozen lakes, Opie considers these places for their sublime beauty and mines them for their aesthetic potential.

Place visits Highschool Football Fields, American Cities, Houses, and 1999 among other projects, while reserving two noteworthy gatefolds. One for 700 Nimes Road displaying the contents of Elizabeth Taylor’s closet(s). The other, for a project titled Alaska. For 700 Nimes Road, page 148 sits across from page 153. The gatefold strategy asks readers to open the pages in the opposite direction to act out the big reveal, enabling a view of four images at the same time. Alaska takes the gatefold a step further, showcasing 9 photographs upon expanding. This works brilliantly at illustrating how the work appears during an exhibition. It also provides insight as to how Opie approached Alaska. Each shot photographed as a vertical (or in portrait orientation), knowing full well that as an installation the rendering would be a long panorama, tied together by the shoreline running through the nine frames. Similar strategies are applied during the making of Icehouses and Surfers.

Place finds home to seven images from the Portraits and Landscapes series, all untitled #2,5,9,14,17,15,16 (dates: variable). Mentioned here as they evidence Opie’s malleable approach to the medium. Choosing to produce images out of focus in order to evoke an ethereal sensation of place. Continuing the wide spectrum of photographic possibilities are Somewhere In the Middle (pg. 193,195), which share kinship with color field painting. Freeways, (pg.172-175) on the other hand, are printed as historical documents (irony noted) via the platinum printing process. It’s an instance of her dialogue with the history of photography, specifically with 19th century French photographer Maxime Du Camp and his photographs of the Egyptian pyramids.

Place takes Opie far and wide, imagining an endless road trip. But it does not ignore her home and local environs – finding ample subject matter to explore and document. Her camera is inclusive, even finding its way to swamps to find beauty in unexpected places. Swamps is at once rhetorical and referential at the same time, as Opie notes in her interview with Ms. Cotton. Positing an agenda of ecological preservation as she cites her photography as bearing witness to the inevitable change that lies ahead. A photo from Swamps (pg. 214, untitled #1, 2019) punctuates the Place to segue towards the final theme: Politics. Here, the phrase, draining the swamp takes on new meaning.

Politics opens with a black and white photo of a hand holding a lit candle. It’s a still from her film, The Modernist. It functions to provide possible entry points to the final theme, allowing readers a chance to interpret for themselves. A symbol of hope, a somber vigil, a celebration or an arsonist’s tool–to burn it all down–or still yet– some combination of all four. At the opposite end, closing out Politics is a photograph titled: Self-Portrait, November 2, 2004 imaging the voting booth with unambiguous messaging.

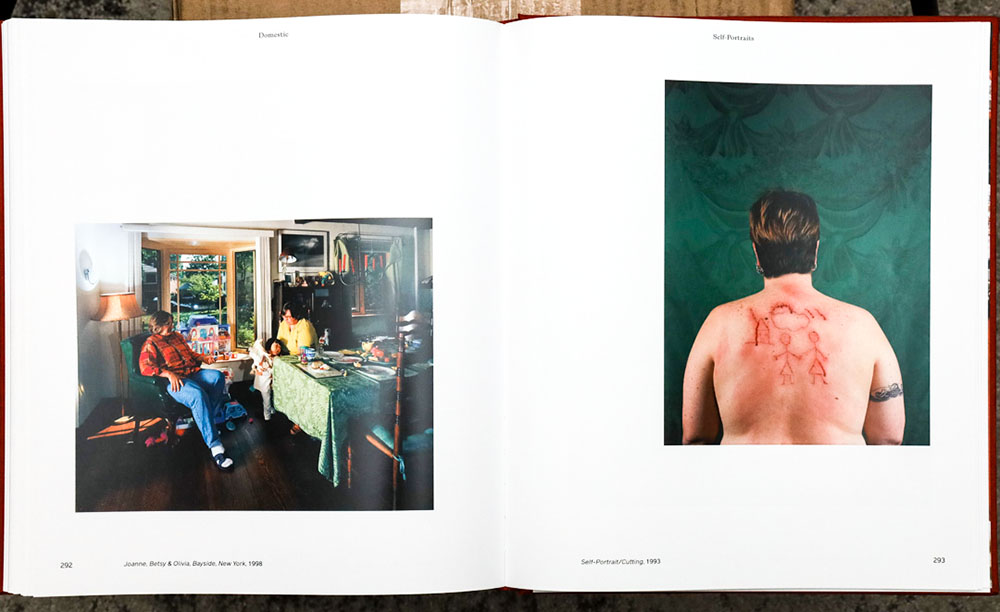

As could be anticipated, Politics makes visible Opie’s affinity for documentary photography. Having cited documentary photographer Lewis Hine as an early influence, she learned, at a young age, of the power to effect change inherent in images. This lends greater efficacy to her practice as a documentarian. Opie continues to emphasize an approach that is first and foremost: varied. No less than sixteen projects are represented among the eighty pages comprising the Politics section. Among these pages one will find two of Opie’s most personal works: Self-Portrait/Pervert, 1994 (pg.258) and Self-Portrait/Cutting,1993 (pg.293). The two photographs are also, arguably the most impactful as well. Opie has spoken at length as to how these two images represented turning points in her life and career.

Tightly cropped, framed and modest in size, against a bright yellow backdrop are six individual portraits from Being and Having 1991. All wearing fake mustaches and directing their gazes back at the viewers. Being and Having was at the forefront of the art world’s engagement with identity politics throughout the nineties. Opie interjects her brand of deadpan humor with the inclusion of name plaques: Pig Pen, Chicken, Whitey, Chief, Oso Bad and her own alter-ego, Bo. The use of the final gatefold displays how one experiences the work in a gallery setting with the eyes of the sitters aligned perfectly on a horizontal plane.

Politics never stray too far from home as In and Around Home shows. Using Polaroids to capture events unfolding in front of her via broadcast television, they suggest a presence, mediated as it is, in need of documenting– to bear witness (again to use her phrase). While also using her camera(s) to document protests occurring just outside her window–figuratively speaking. In Politics, Opie also makes the media covering the demonstrations the subjects, deconstructing the apparatus of news dissemination. With many images from across Opie’s photographic spectrum finding placement in Politics, one can easily apply the quote from guest essayist Helen Molesworth that “All Art is Political”. But as Phaidon’s Catherine Opie exhibits, it’s politics through the eyes of an artist that make all the difference.

All told, Catherine Opie succeeds in providing breath to an exceptional body of work. Closing the back cover, the reader can comfortably conclude they have witnessed the photographic evolution of one of our most important photographers of our time. Catherine Opie also hints at much more to come, because that is what prolific artists do.

_____

Catherine Opie, by Cathy Opie

Editor: Simon Hunegs

Photographer: Catherine Opie, born in Sandusky Ohio, USA; resides Los Angeles, California, USA

Publisher: Phaidon Press Inc. (New York, NY, copyright 2021)

Introduction: Elizabeth A.T. Smith

Contributing essayists: Hilton Als, Douglas Fogle, Helen Molesworth

Interview by: Charlotte Cotton

Text: English

Hardcover book, sewn binding, four-color lithography, 338 pages, 13×11.25 inches, printed in Singapore

Photobook designer: Garrick Gott

_____

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).