Review by Steve Harp ·

In 1975 Martha Rosler exhibited a group of 24 diptychs titled “The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems.” The work juxtaposes banal images (think of Ed Ruscha’s gasoline stations) of rundown facades in New York’s Bowery district with text panels listing euphemisms for inebriated states (“blind drunk,” “dead drunk,” “embalmed,” “buried,” “gone”). The effect of this pairing is to lead the viewer to question what, exactly, documentary photography – even when accompanied by text – communicates or can communicate.

A less overtly didactic example of documentary text-image collaborative projects is James Agee and Walker Evans’ 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Less wry and more earnest than Rosler’s project, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is, in many ways, not about the ostensible subject (“three sharecropper families”) at all, so much as it is about Agee’s response to what he encounters and the impossibility of adequately conveying that encounter. Somewhere between these two approaches lies Cornelia Suhan’s Silent Witness. All three projects explore the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of documenting the world through photography and language.

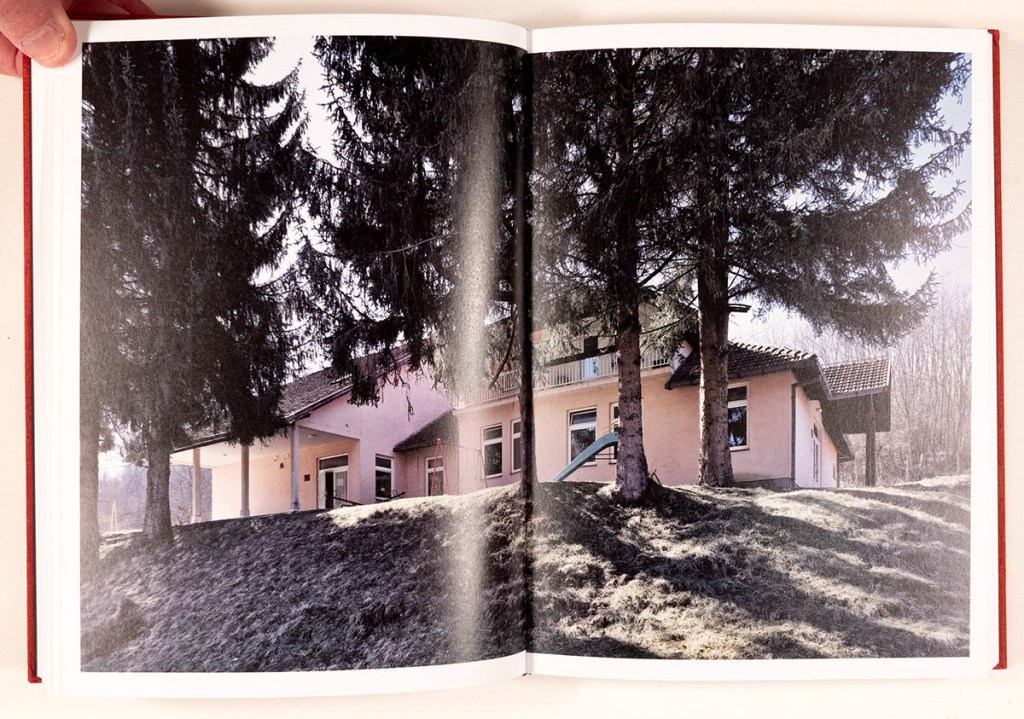

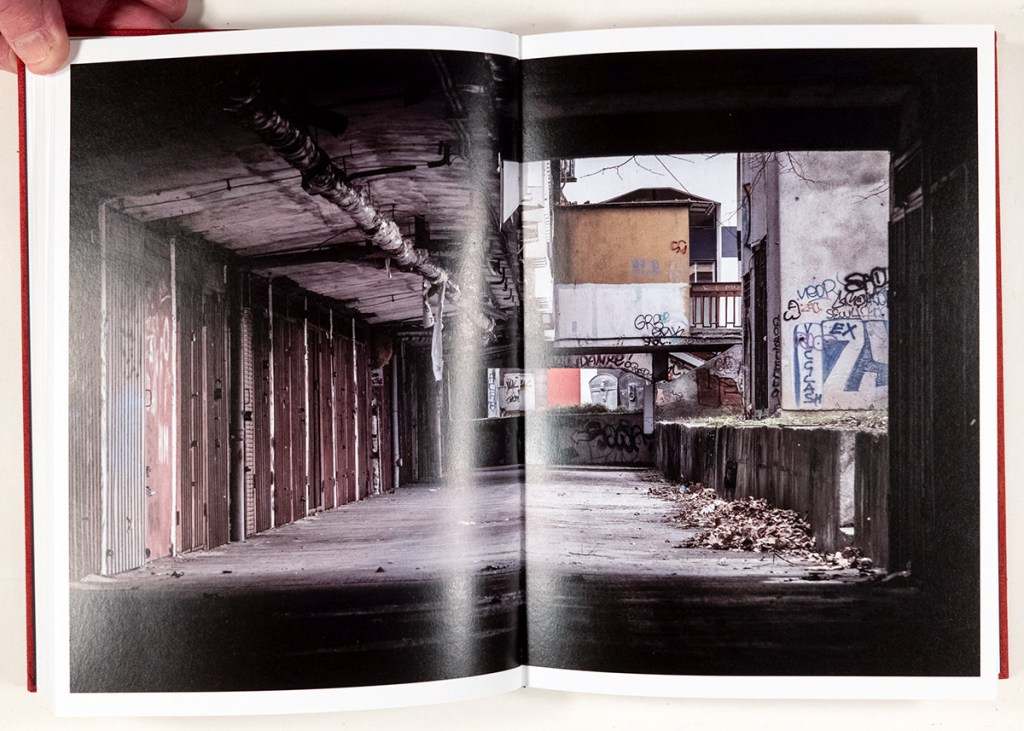

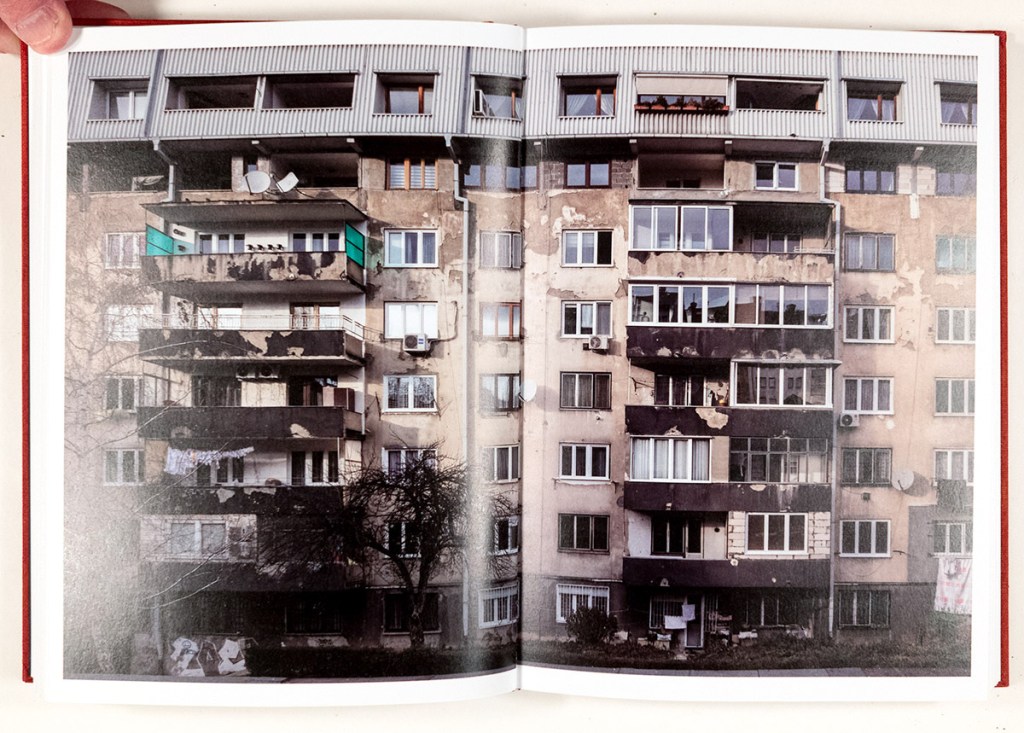

Silent Witness is “about” the history of war crimes – primarily rapes – carried out in the Bosnian War of 1992-1995, the “silent witnesses” being the buildings in which the crimes occurred. Yet the book is anything but silent and the play between speech and silence, revelation and obfuscation renders the book – and its testimony – complex and unsettling.

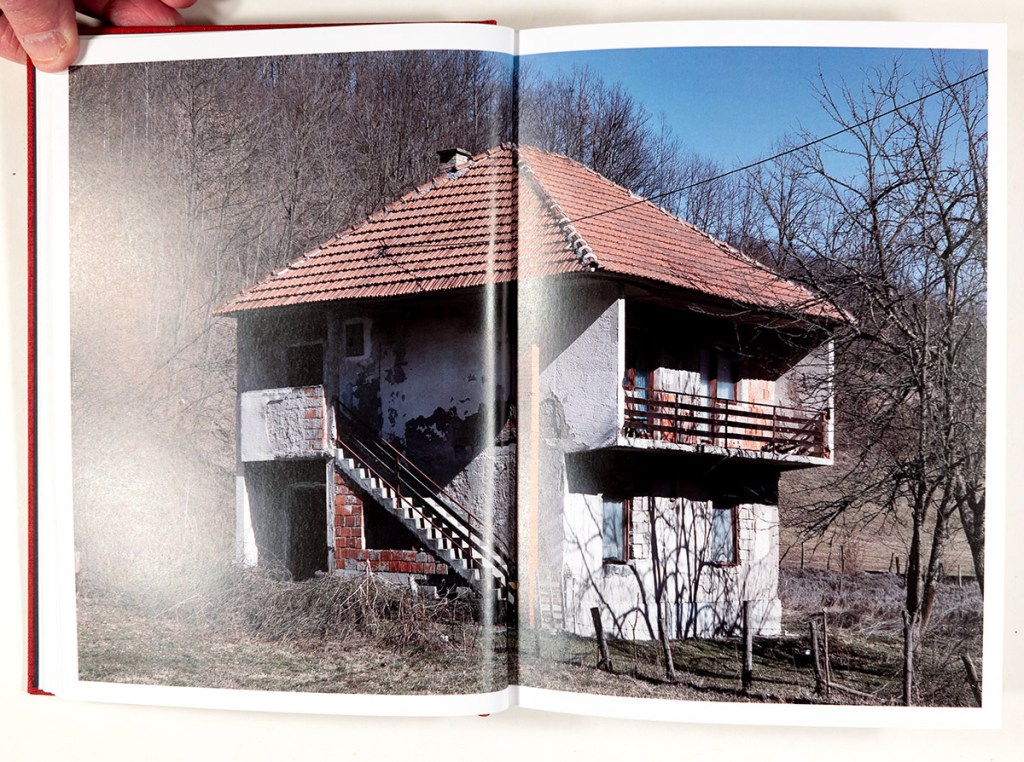

A description of the physicality of the book might be an appropriate starting point. Hardcover, 9.5 x 7 inches and more than an inch thick, this is a solid volume. My initial sense was that it resembles nothing so much as a history or textbook – it does not present as a traditional “photography book.” This impression is further substantiated by the amount of text in the book. Of its 192 pages, nearly half are completely text or contain significant textual material.

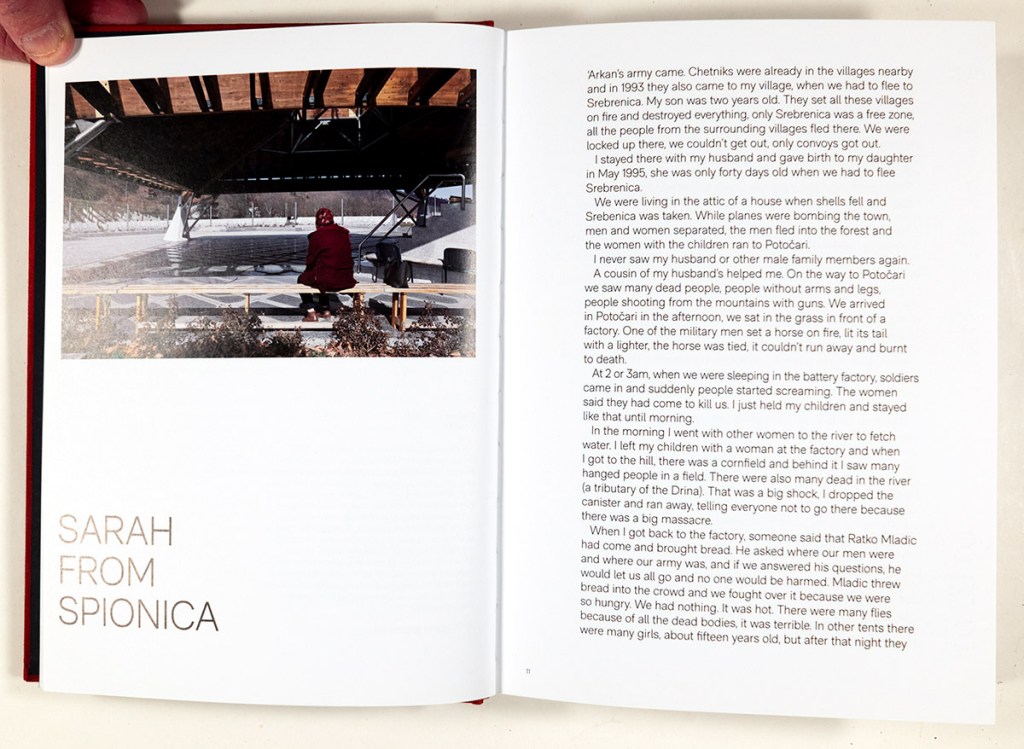

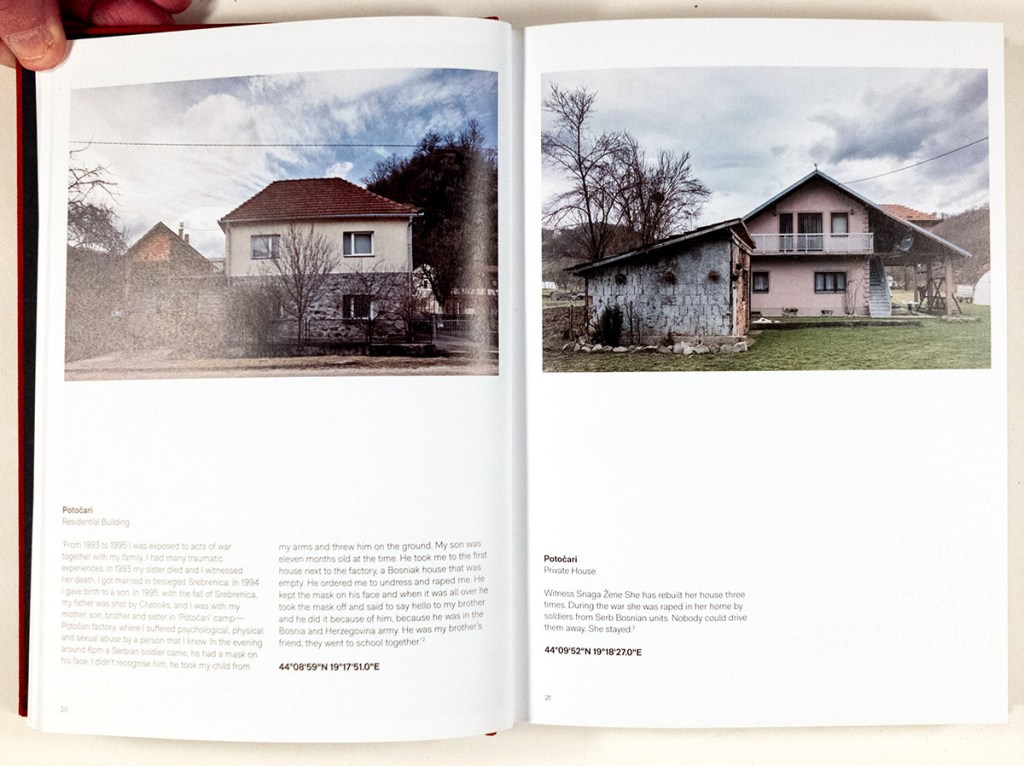

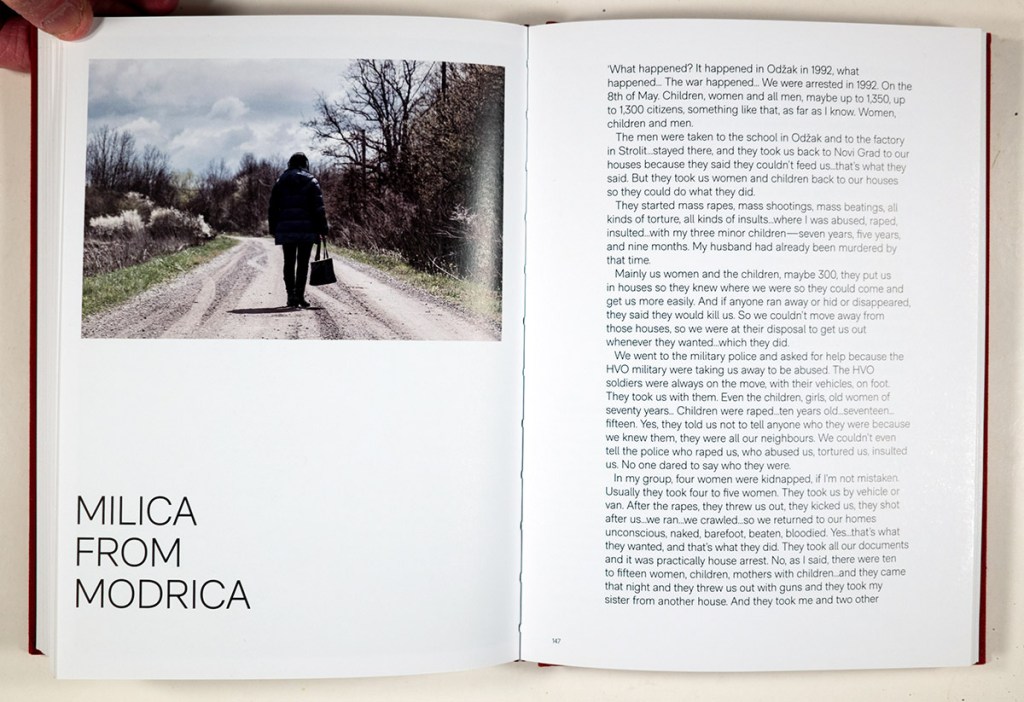

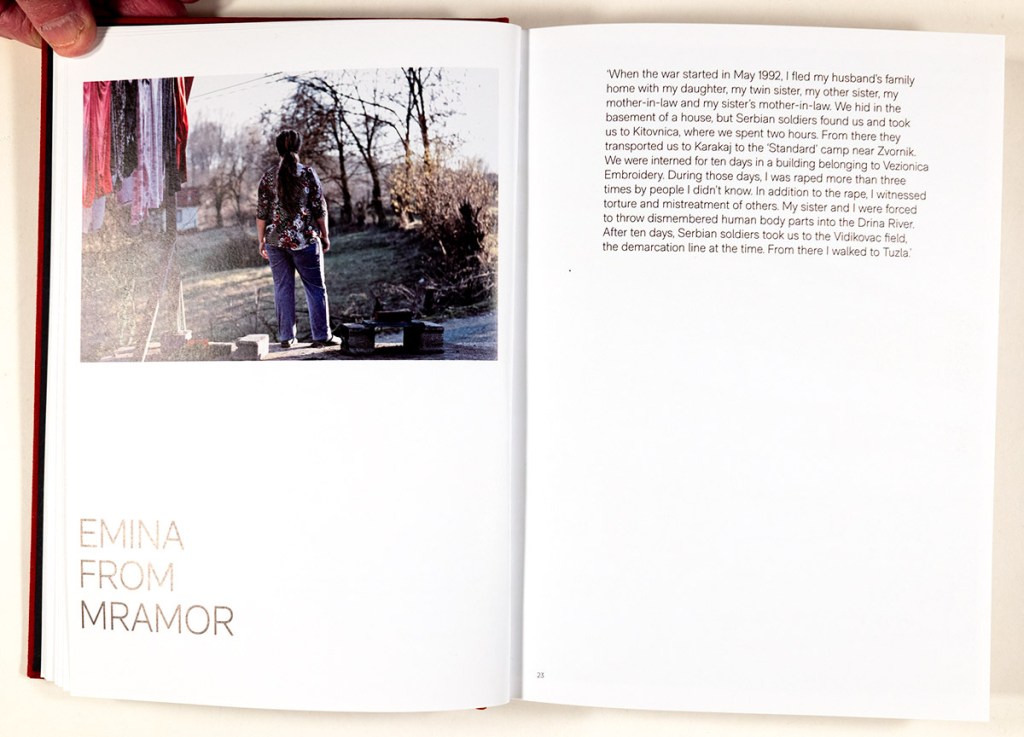

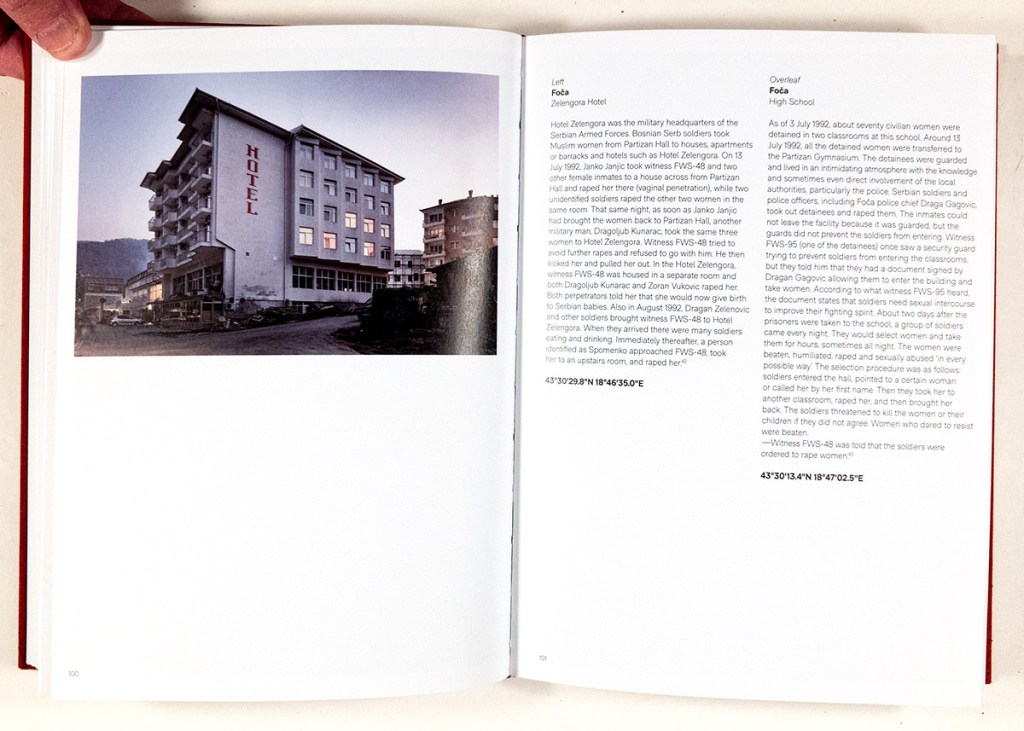

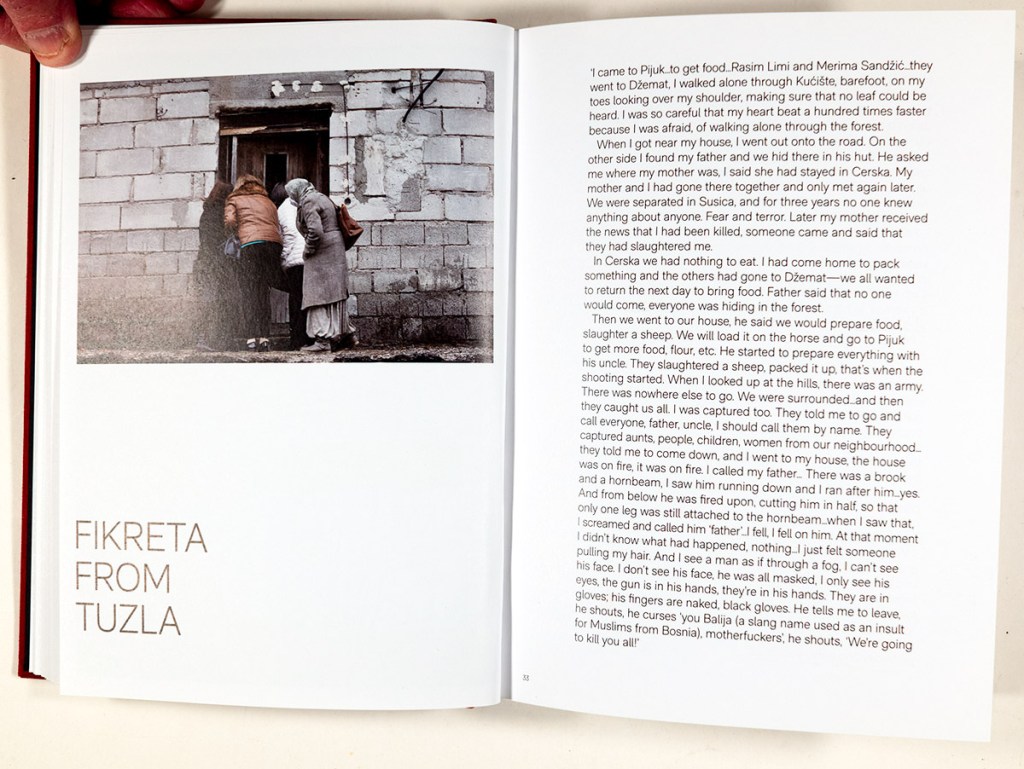

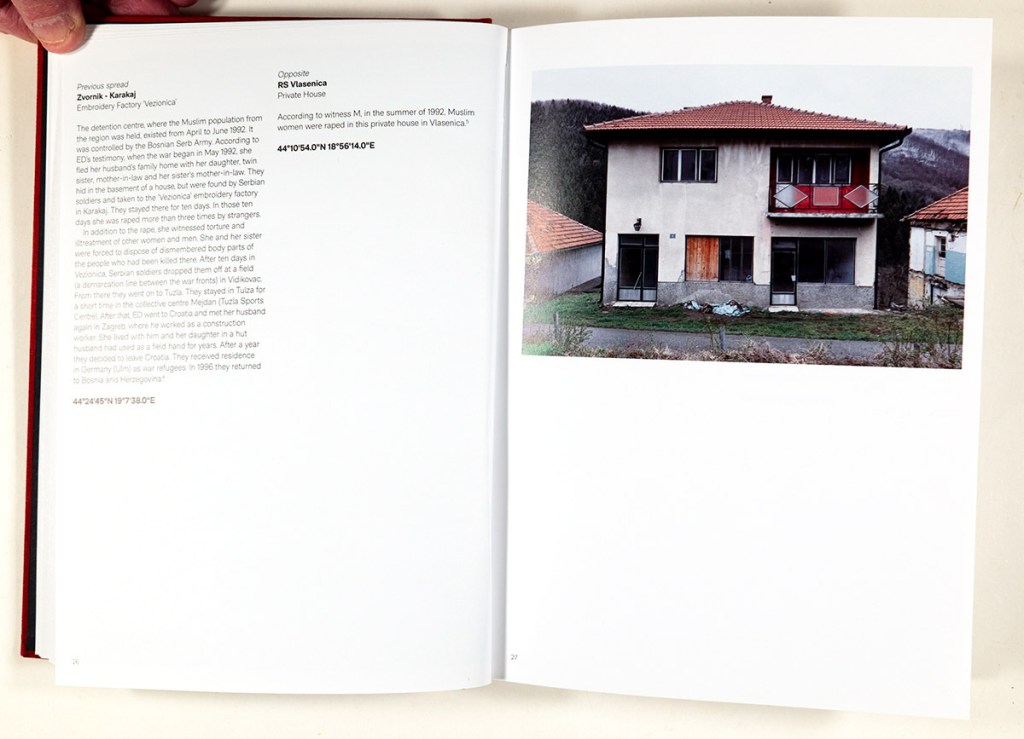

The book opens with an essay by Verena Bruchhagen professor of women’s studies, at the Technische Universitat, Dortmund, considering perspectives on witnessing – remembering and documenting – war crimes after the fact, the “paradoxical simultaneity of making visible and concealing,” followed by the stories of nine women who experienced these crimes. The book, then, offers itself as a body of evidence – images, testimony, documentary descriptions and explanations. Each photographic description is accompanied by a precise geographical co-ordinate of location (ie 44°43’49.1”N 18° 05’05.0”E). The book is inhabited by a variety of voices – victims, witnesses, mysterious voices of authority, history, knowledge that attempt to weave together a story horrendous and unspeakable, voices that desperately try to understand and explain what “happened.” Despite the assertion by Nusreta from Prijedor that “Their story will never be heard,” Mileca from Modrica eloquently pleads , “Shouldn’t I talk?”

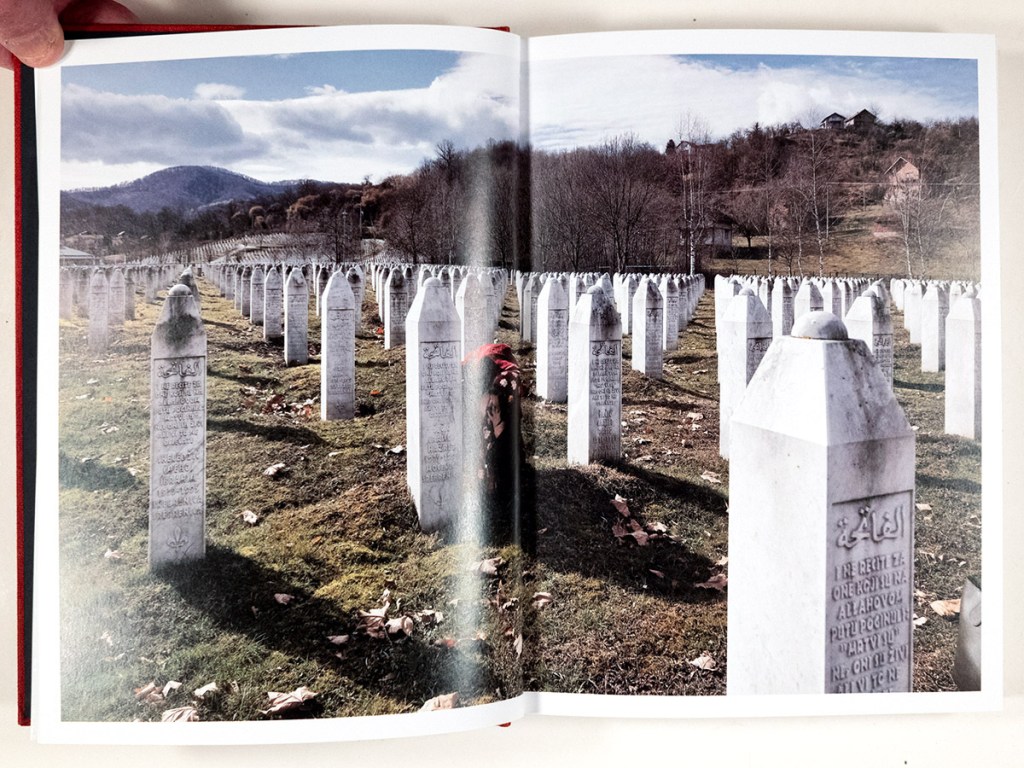

Nusreta, Mileca and the seven other female victims of these crimes voice their stories throughout the book, providing something of a Greek chorus in recounting the tragedy. These are interspersed with a “neutral” voice explaining the significance of each “silent” building and location we see, describing (partially, of course, for a complete view is inherently unattainable) the events that took place within. I was reminded of Roberto Bolano’s last novel 2666 and its fourth (and longest) section: “The Part About the Murders,” in which the reader is given page after page of police report-like descriptions of an unending series of unsolved rapes and murders occurring in the fictional Mexican village of Santa Teresa. The war crimes described throughout Silent Witness are no less unrelenting though factual. And this sense of the unrelenting is what unsettles this book and gives it its haunting power. For, as a reader and viewer I’m overwhelmed by the sheer scope of the atrocities described as well as the impossibility of depicting them.

While the descriptions (as recounted through text) of atrocities are graphic and explicit, the visuals, as mentioned above, are rooted in the hidden and banal. The “silent” images of the locations of the crimes suggest nothing so much as real estate photographs (again, Ed Ruscha’s photographs are called to mind). Some interiors, some aerial views but mostly we’re given exterior views of the buildings in which the crimes were committed. There is a single photograph of each of the nine individual witness/victims. Each is visually depicted either from the back or from a distance or with her face otherwise unseeable or unrecognizable. The images themselves tell us nothing of the crimes that took place – and that exactly accounts for their power. The silences in this book scream.

In the section on “Mirjana from Visegrad” we see an aerial view of the landscape of Potoci. In part, the descriptive text reads “What can no longer be seen . . .” This could as well serve as the title for the book. The book ends with an essay by the photographer, Cornelia Suhan discussing her process in approaching and carrying out this project. In the penultimate paragraph she writes: “I kept asking myself ‘How can I use a visual medium to tell about an event that is no longer visible?’ “

The paradox of photographing what’s not there might be thought of as central to all photography. Despite its claims to freeze time and capture appearance, photography only ever depicts what’s absent, what is no longer there. The tragedy here (as in the case of all crimes) is the absolute necessity of attempting to witness – through image as well as language. We might give the last word to Muska from Tuzla: “We are survivors. I would never want it to happen to anyone again, and it should be heard about, written about and passed on . . . “

____

Steve Harp is a Contributing Editor and Associate Professor The Art School, DePaul University

____

Silent Witness, Cornelia Suhan

Photographer: Cornelia Suhan; born in Duisburg, Germany and currently resides in Dortmund, Germany

Publisher: Gost Books, London; copyright 2024

Texts by Verena Bruchhagen and Cornelia Suhan

Text: English (German edition available)

Book description: Hardback, printed by EBS (Editoriale Bortolazzi-Stei), Verona Italy

Book edited and designed by GOST (RossellaCastello, Katie Clifford, Gemma Gerhard, Justine Hucker, Alion Kaye, Eleanor Macnair, Claudia Paladin, Ana Roche)

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

____

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff sand the photographer(s).

Leave a comment