Review by Steve Harp ·

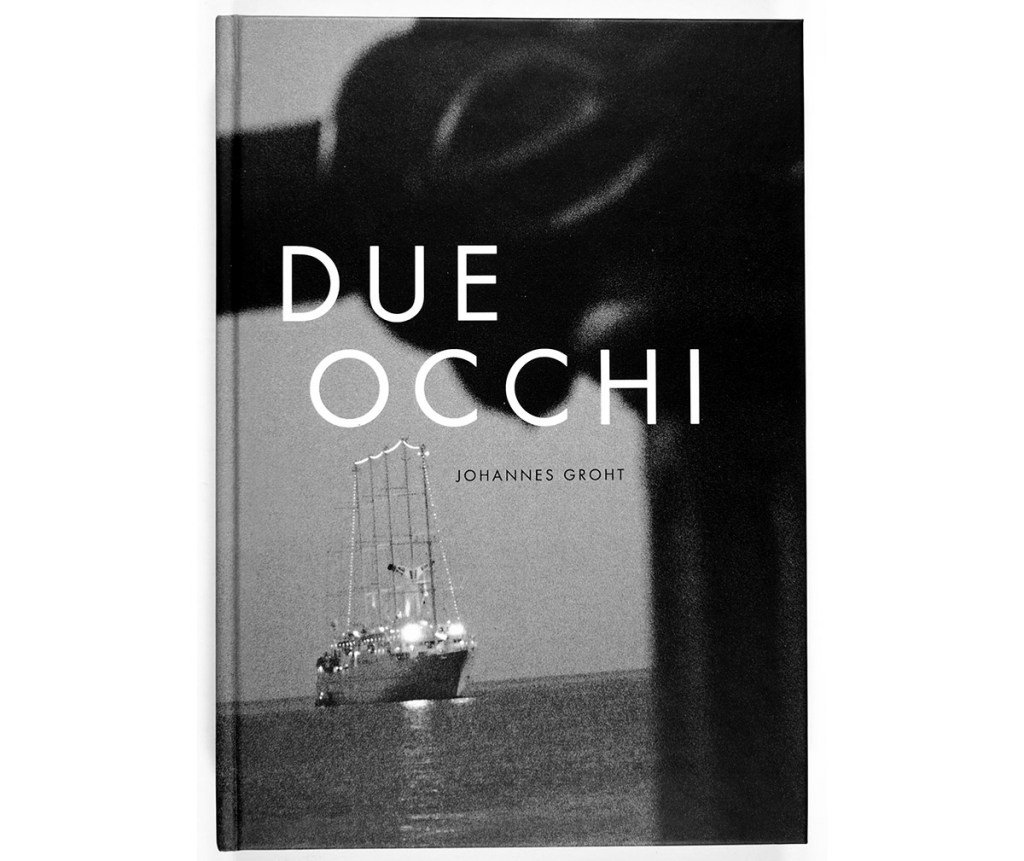

Due Occhi, the title of Johannes Groht’s new monograph, can be translated from Italian as “two eyes.” Before considering some of the associations triggered (to use Groht’s term from the artist’s insert included in the review copy), we might first pause to consider the “newness” of the book. Published in 2020, the book (again quoting Groht) “got lost a bit in the pandemic.” The sense of lostness, of blind wandering, resonates, I’m sure, with many of us in so many ways in connection with that recent, yet seemingly so distant time. And the blindness that we find ourselves only now seemingly climbing out of might be a useful opening for considering this visual exploration of Italy’s southern coast.

The book takes as a central metaphorical figure, Santa Lucia of Syracuse, a Christian martyr who, according to legend, had her eyes gouged out prior to her martyrdom. In his statement, Groht writes, “In depictions of the saint, the martyr holds a bowl with two eyes in her hand that look at the viewer.” A kind of pre-photographic instance, then, of Roland Barthes’ notion (from Camera Lucida) of the “blind field”: “…a kind of subtle beyond…“ that makes the photograph look back at or “animate” the viewer. This sense of looking but not seeing (or understanding) in tandem with the images seeming to look back at us is pronounced throughout the book, suggesting a “blindness” on the part of the viewer.

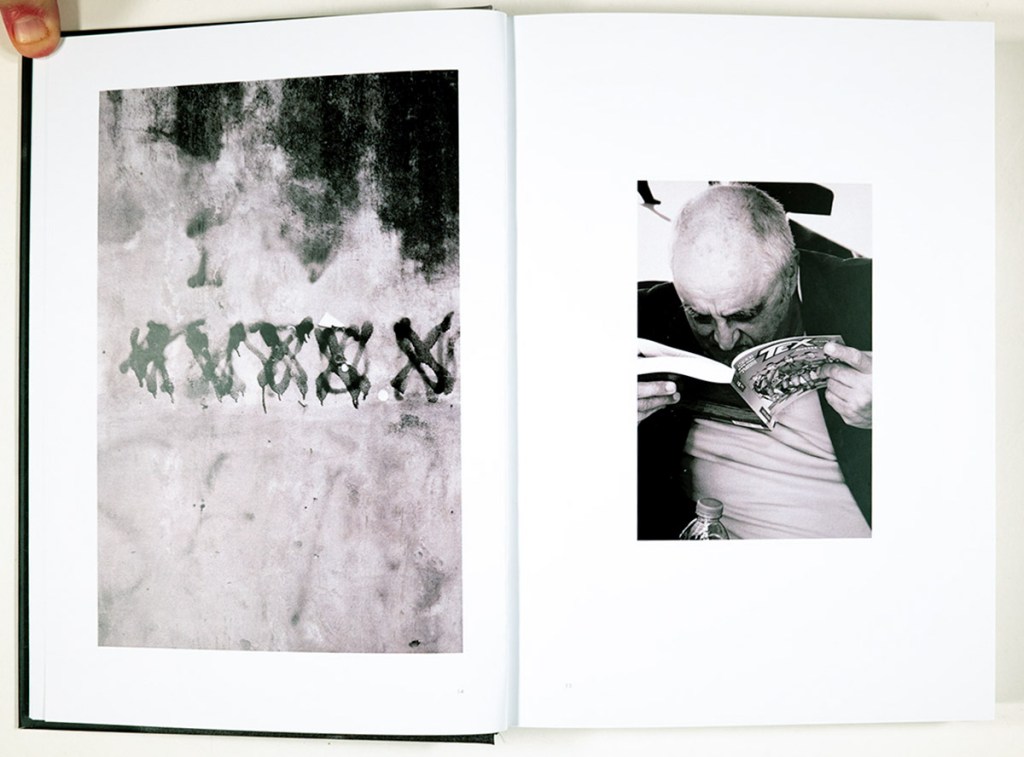

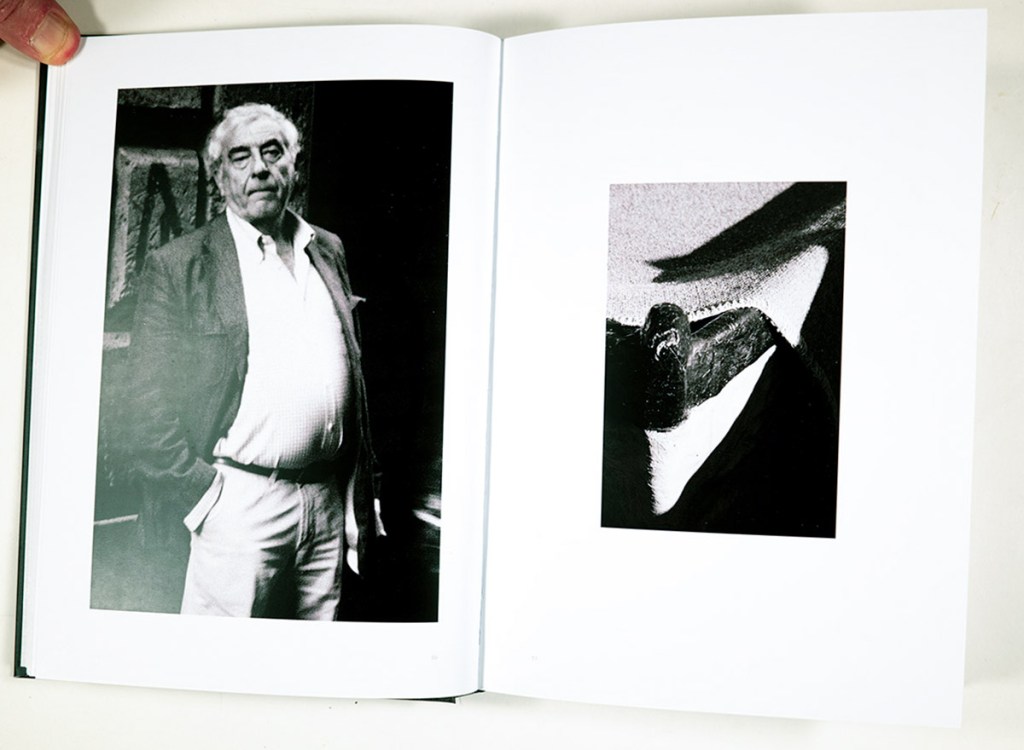

A less metaphorical (as well as less gruesome) association to the occhi (eyes) of the title would be a consideration of the prominence of looking and eyes running through the monograph. As early as p. 15 (of the 232-page volume) we are given an image of a man who seems to have limited vision holding a book nearly to his face, a book which appears to be a graphic novel – a book of images. Consider also the spread on pp. 122 – 123: four sets of eyes, one belonging to a pedestrian in sunglasses, the other three belonging to figures in a religious engraving. All eight eyes are darkened, obscured – hidden from the viewer.

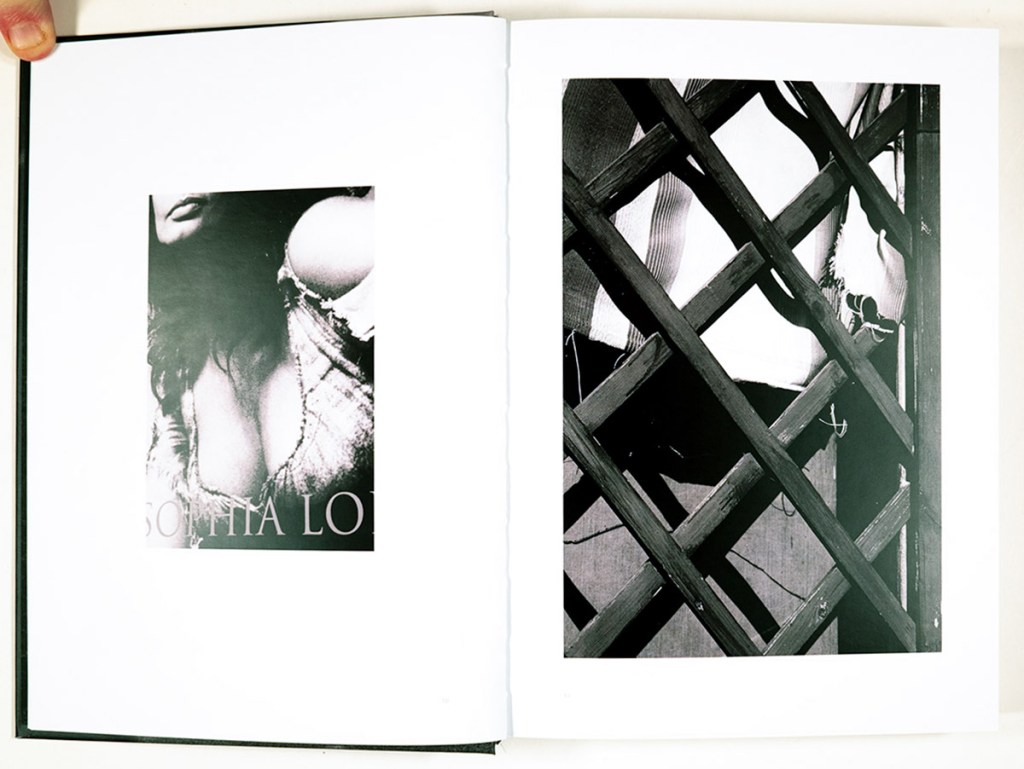

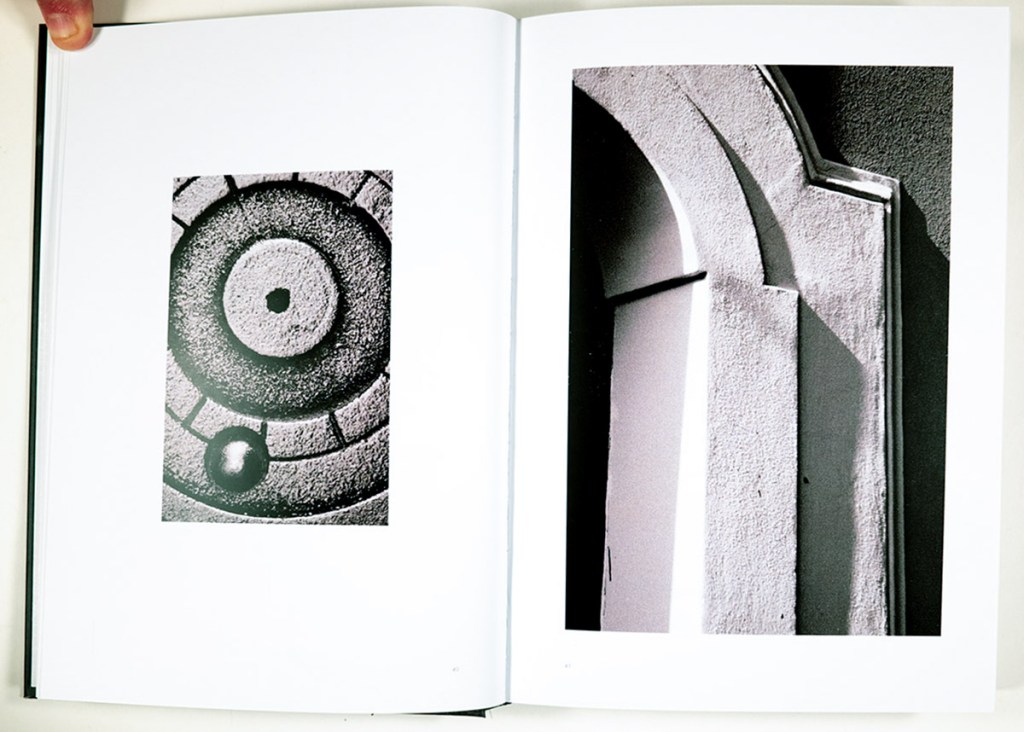

We who look through the images in Due Occhi are thus made aware of the physicality of sight, of looking. Looking as a form of struggle continues throughout the book as we not only see figures seeing (or trying to see) but we also struggle with much of the image world Groht brings us: what are we looking at? Where is it? What is its context? How do these image slivers connect?

There is, of course, an implied geographical connection. As Groht writes:

The pictures were taken at the foot of Vesuvius in Naples, on the Amalfi coast and in Salerno, in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

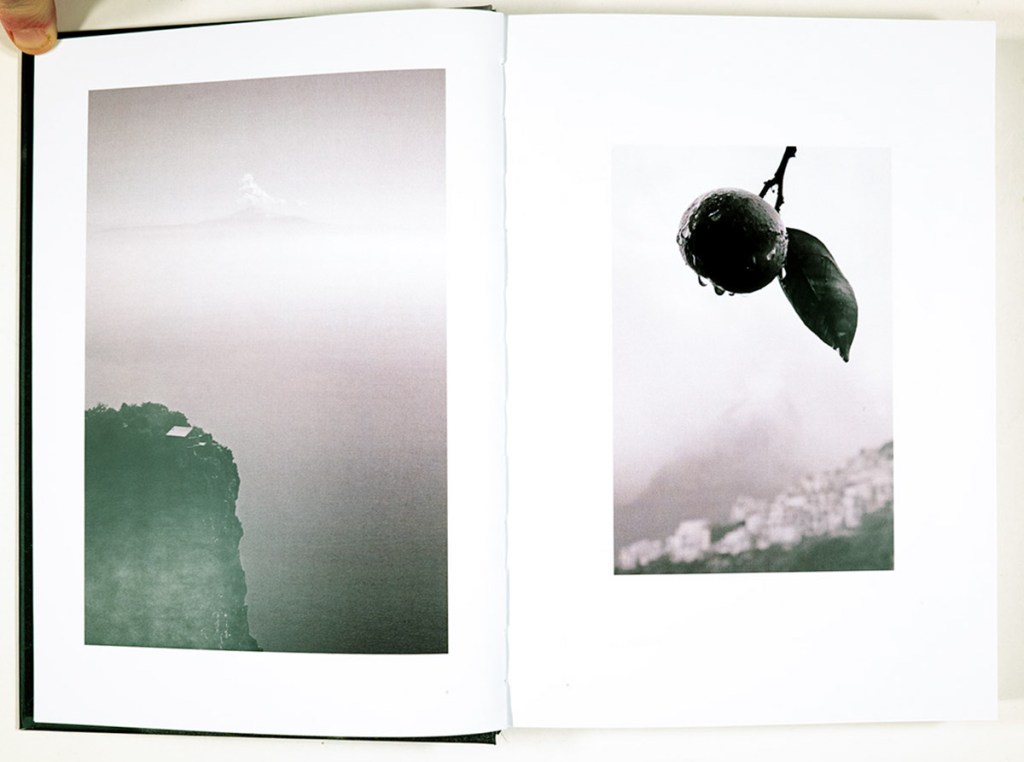

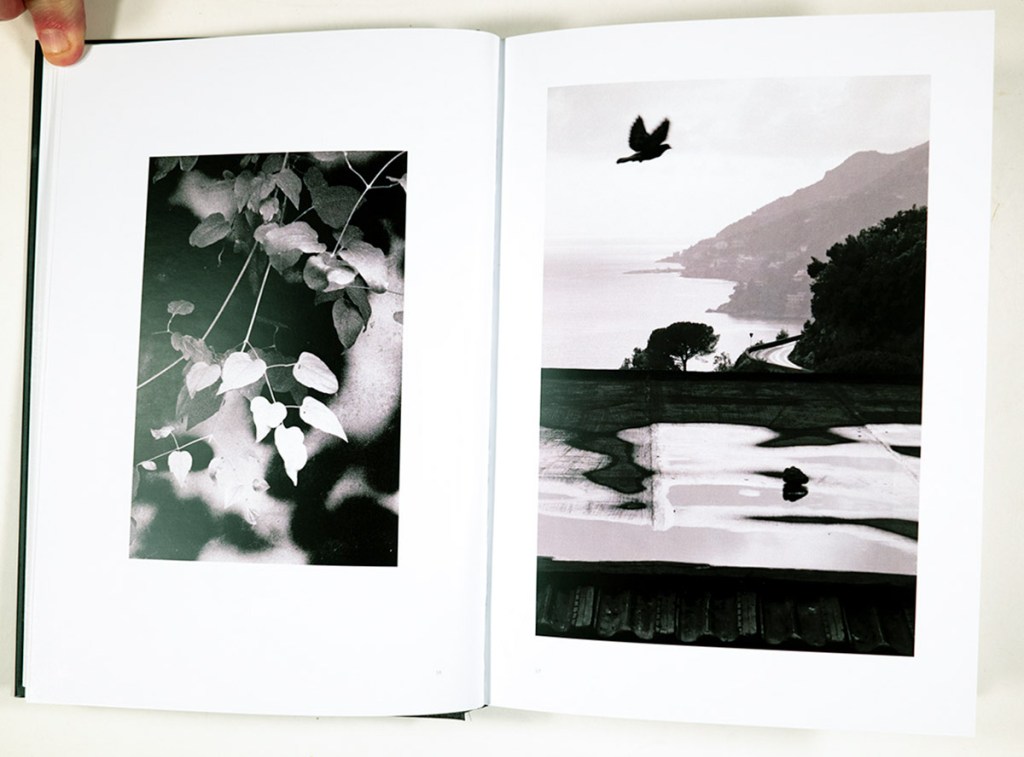

But this is not a conventional “travelogue.” We are given fragments, clues in a mystery. And so, we as viewers of the book look. But what do we see? Many of the images are so visually striking and compelling that the viewer is left simply marveling at the construction of the frame. Groht could, probably, have made our looking (or deciphering of the “mystery”) easier or more direct with fewer images.

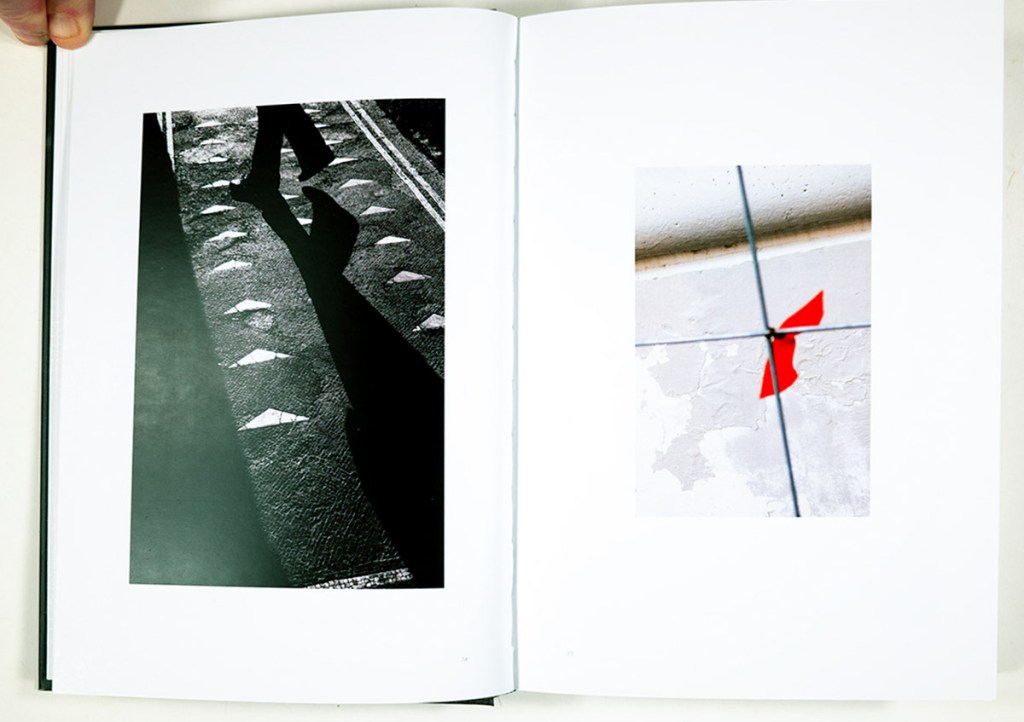

But would that approach have worked counter to what is implicitly being suggested about vision? That an excess of images presented as fragments leads to a kind of blindness? Due Occhi contains 199 images in 13 “chapters” over 232 pages, mostly black and white, but about a quarter of which are in color. Physically, the book object is a substantial hardcover, 7” x 9.5”; 1” thick.

The notion of due or twos runs through the book as well. In considering this aspect I was reminded of the opening section of Walker Evans American Photographs (1938) which, among the motifs introduced in the first 10 photographs, is the theme of pairs or twos. The pair is an organic strategy in Due Occhi as virtually every page spread (other than the opening and closing image of each chapter) is “arranged in pairs on double pages” as Groht tells us in his statement.

Every spread, then, is a diptych to be read, images-pairs to be compared, that talk to each other in ways clear and (mostly) unclear. This sequential approach to organizing photographic books in dipychs was used subtly and masterfully by Nathan Lyons, particularly in Notations in Passing [1974] and Riding First Class on the Titanic [2000]. Again, vision is work on the part of the viewer, a struggle to decipher and a struggle out of blindness, to see and see complexly.

The pairing of images to be considered together not only suggests the diptych as a visual structure but also a basic physiological aspect of human sight – binocular vision. In binocular vision, two different images are combined or merge to create a single image with more depth and complexity than a single image seen alone. In the physiology of human eyesight, each image is subtly different. Here, more distinct differences between images can be thought to combine subtly into a metaphorical single image or concept.

Near the end of Camera Lucida, Barthes remarks on the distinction between looking and seeing:

…how can we look without seeing? One might say the Photograph separates attention from perception, and yields up only the former…

Due Occhi is a book is filled with visual treasures and delights for the eye (or eyes), yet one that demands effort on the part of the looker in order to see and perceive. It is said of Santa Lucia, patron saint of the blind and those with eye illnesses, that when her body was prepared for burial it was discovered that her eyes had been miraculously restored. Groht seems to be implying, that we – like Santa Lucia – can only really see by being willing to be on some level uncomprehending or “blind.”

____

Johannes Groht has been featured previously in PhotoBook Journal: Nice Not Nice

____

Steve Harp is a Contributing Editor and Associate Professor The Art School, DePaul University

____

Due Occhi, Johannes Groht

Photographer: Johannes Groht; born and resides in Hamburg, Germany

Publisher: self-published, Hamburg, Germany, 2020.

Text: German with Statement insert by Johannes Groht in English text.

Book description: Hardcover with thread stitching.

Book designer and editor: Johannes Groht.

____

Articles and photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment