Review by Steve Harp ·

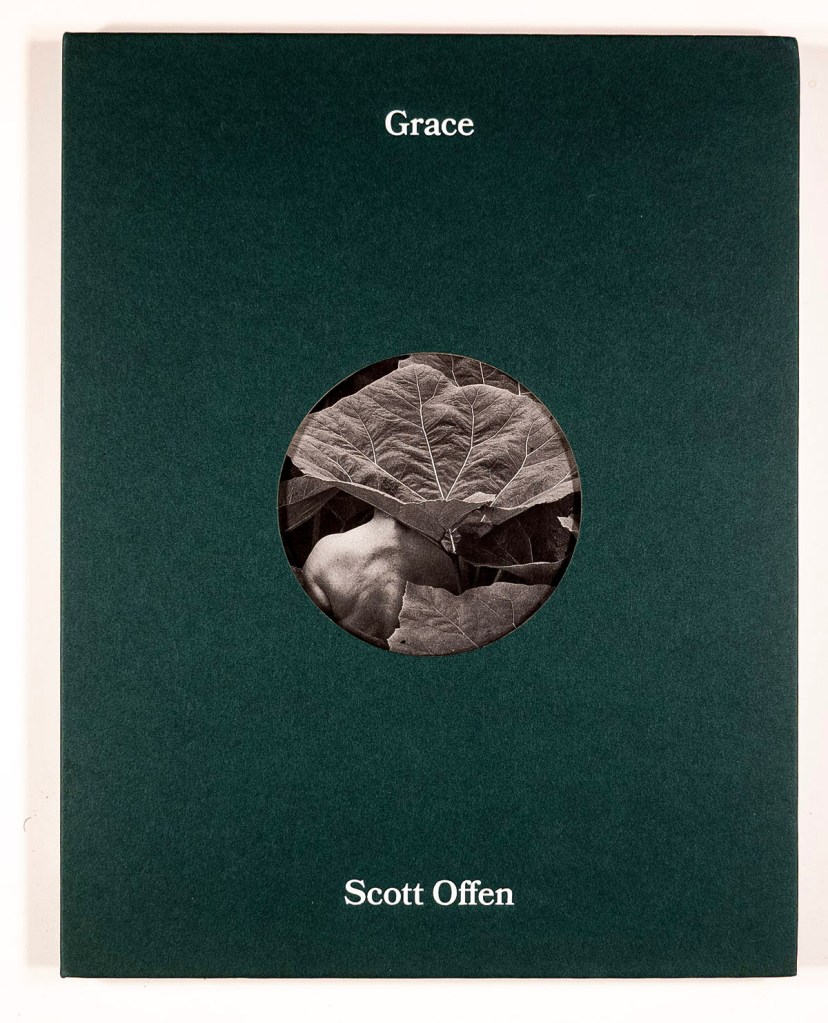

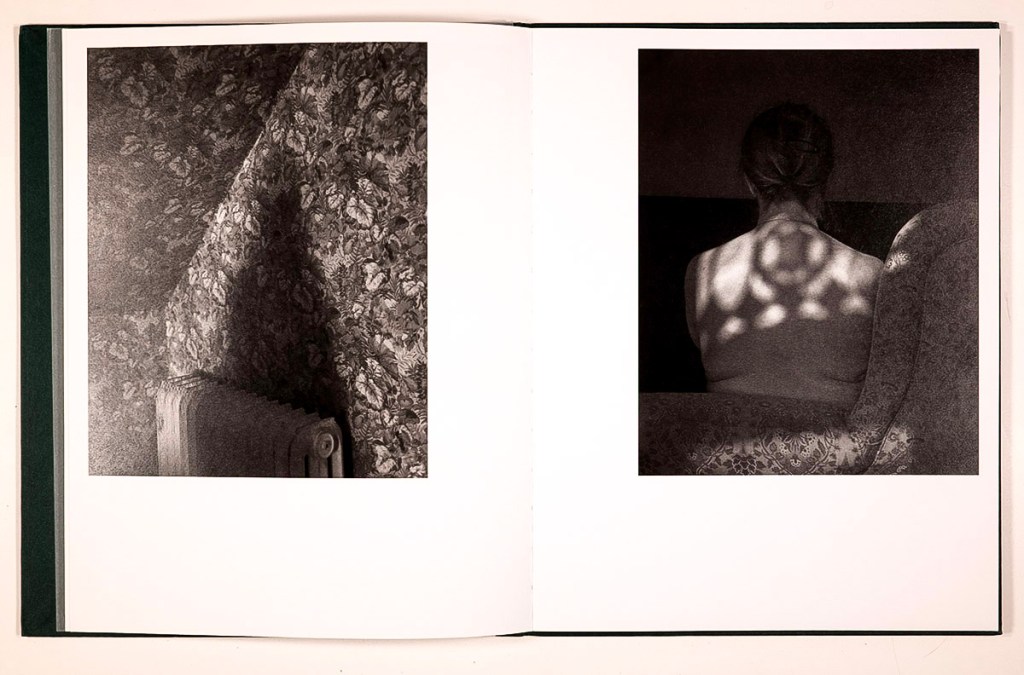

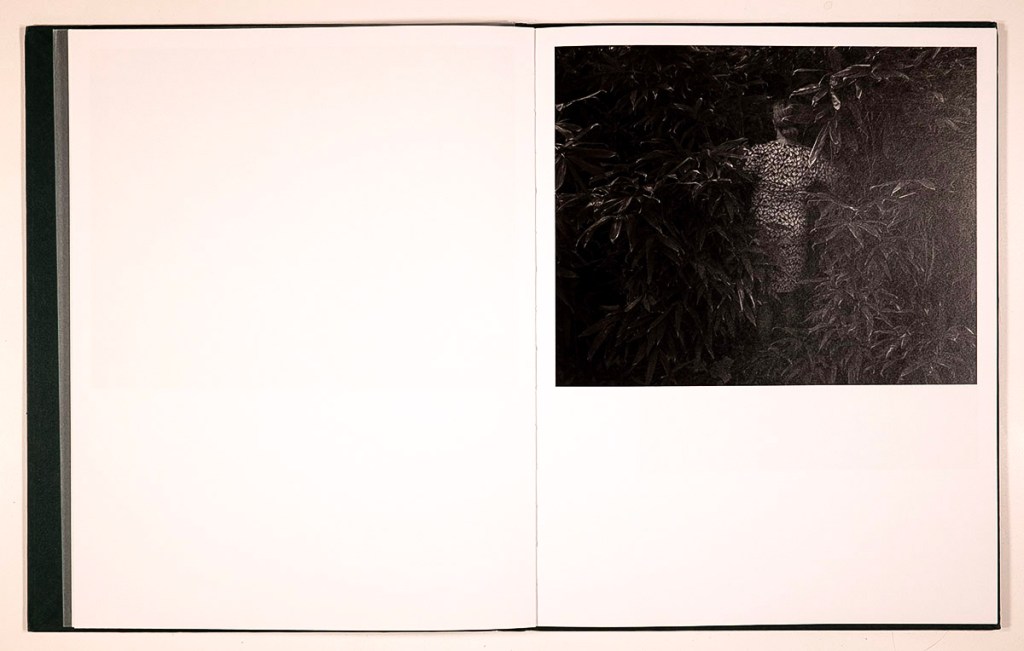

Scott Offen’s 2025 monograph Grace is a lovely book. As an object, its beauty confronts the viewer from the first look – the “porthole” opening cut into the cover gives a view of a tipped-in, beautifully subtle gray-scale image beckoning mysteriously to the viewer. The image, of a large, leafy plant mostly – but not entirely – concealing the flesh of a human figure behind it, is rendered in such subtleties of tone, detail and texture as to give the viewer pause. Upon opening the book, the spine of the cover falls away, exposing the sewn and glued case binding of the signatures, the title page covered by a thick and translucent sheet of vellum.

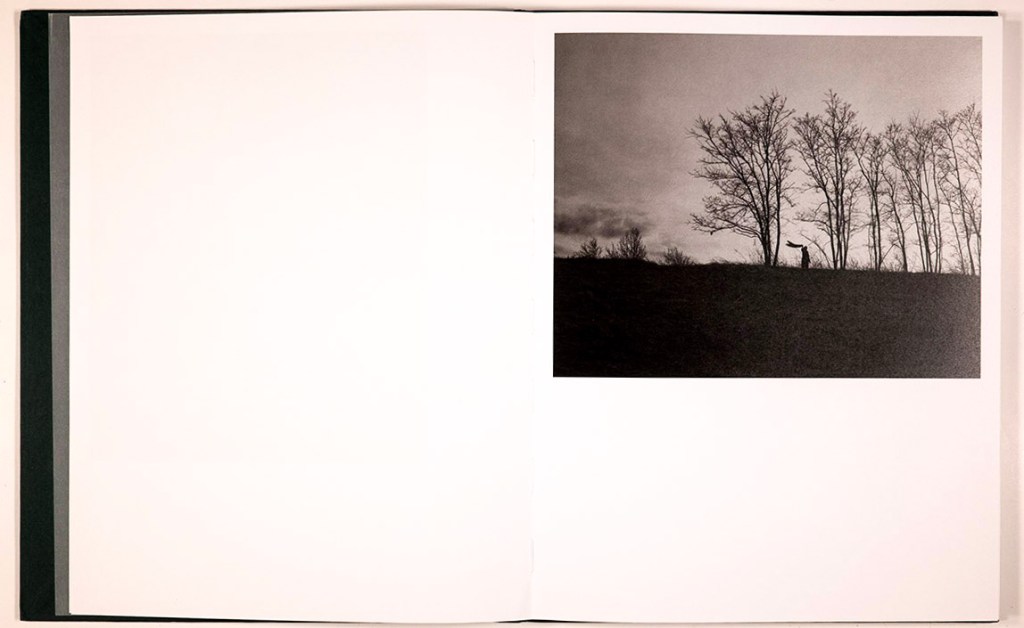

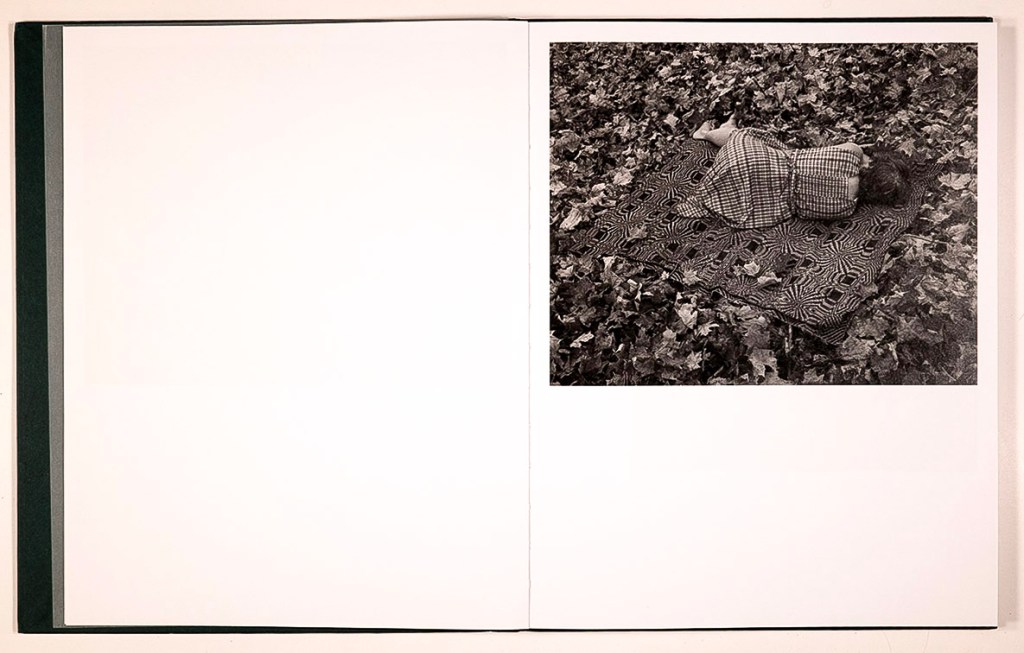

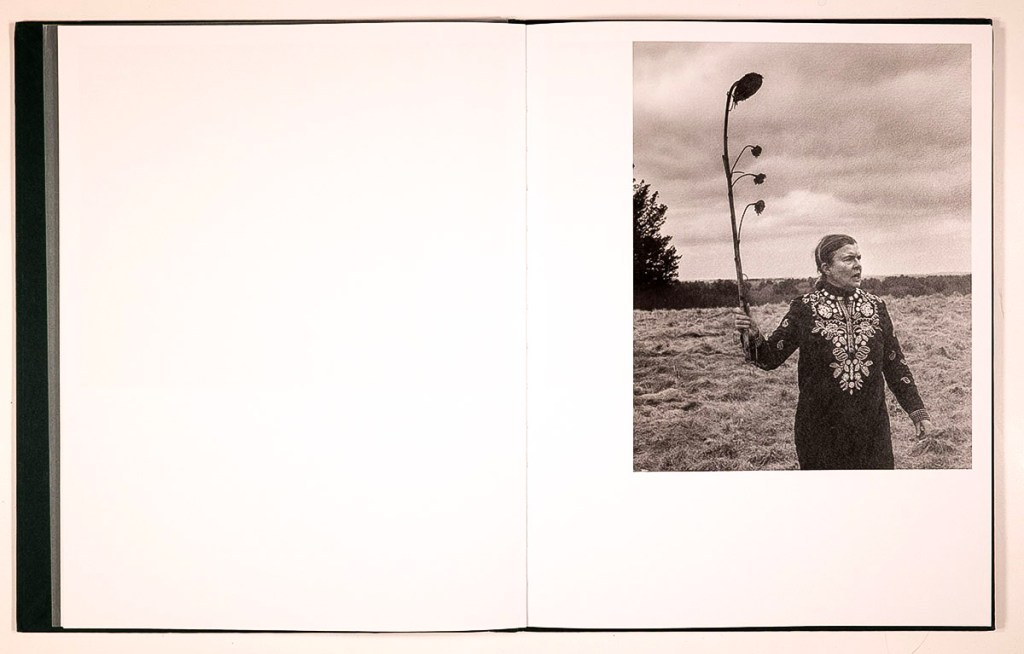

I go into such detail in describing Grace for two reasons. First, to give a sense of engaging with the book as object as being an inherently tactile experience. The tactility of the materials renders the book sculptural. The second reason is to try to communicate a perception of the book as intrinsically mysterious. Who are we looking at? What are we looking at? What is this place? How should we be looking? And who, or what, is Grace? In 30 of the book’s 51 images, we see the figure of Grace – often from a distance or back to the camera or in part or in some other way obscured. I found her presentation most compelling when seen thusly, as a figure of mystery, an indistinct, almost mystical figure. In the end text by Laura McPhee, she is described as “a Nordic goddess preparing for battle, a sylph resting beside a tree, a deity of wilderness.” Grace is a cipher, a figure defined as: “someone or something that is not understood; mystery or enigma” yet at the same time “a person or thing of no influence or importance; nonentity.” Yet this implied figure of myth that Offen conjures is, thankfully, not the perhaps expected female figure of youth and (conventional) beauty but is rather (in McPhee’s phrase) a woman “of a certain age” and in that age, in those markers of age, lies Grace’s beauty and magic. Fewer clear, direct views of Grace I felt might have intensified this impression even further.

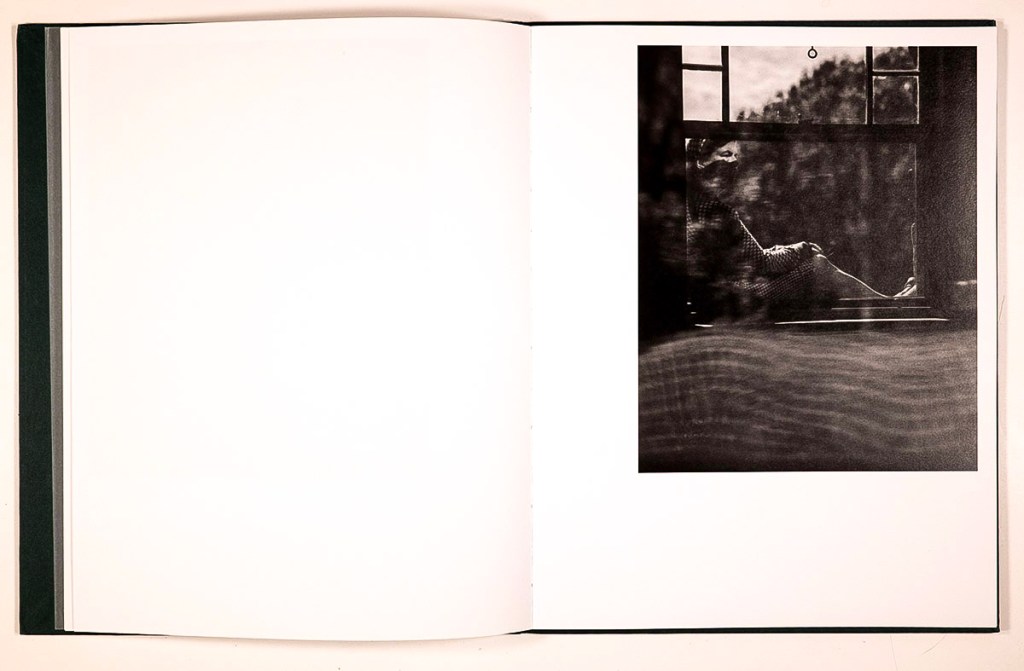

The landscape that Grace moves through in these images, the world the book offers the viewer, the world that Grace is a part (and seemingly the only inhabitant) of, is engaging – indeed captivating – in its nondescript plainness. The predominantly middle gray tonal range Offen presents us, the “fairytale” forest and wilderness and house is subtle and undramatic yet at the same time enchanting in its simplicity. What is this place that is Grace’s realm – simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary, familiar and unfamiliar? The very definition of the uncanny.

I found myself increasingly engaged by this strange portrait of person and place. The more time I spent with the images, the more the sense of inherent dualities spoke to me. Indeed, if we think of grace not (just) as the (presumed) name of the photographed subject, but in the sense of the common noun, grace can be thought, in the theological sense, as “moral strength, a spirit of regeneration or strength, unmerited favor and love” and in a more direct sense as “elegance or beauty of form, manner, motion, or action.” These “splits” are not contradictions so much as (metaphorically speaking) reframings; not visual reframings of camera position or perspective, but of the viewer’s place of comprehension. How should we look at this? How do we see Grace?

Strangely (or perhaps not so strangely) I was reminded of Andre Breton’s surrealist novel Nadja. The Nadja (as character) Breton encounters and presents to the reader is a figure of mystery and desire, one Breton tries to define and frame, limit and control. Breton’s attempts leave the narrator (“Andre”) ultimately helpless and lost. Grace might seem an unlikely photographic project to link to the Surrealists, but I think not really so unlikely. In his writings touching on Surrealist photography, the German cultural critic Walter Benjamin comments on Surrealism being less rooted in the fantastic or the outlandish, but rather the everyday:

“. . . stress on the mysterious side of the mysterious takes us no further; we penetrate the mystery only to the degree we recognize it in the everyday world, by virtue of an . . optic that perceives the everyday as impenetrable, the impenetrable as everyday.”

Photography, Benjamin argues, is a very strange “intervention,” a way of reseeing the familiar. What we are conditioned to see as utterly trivial, what he terms a “profane illumination” is a revelation through the everyday or familiar, what the Surrealists elsewhere refer to as “the Marvelous.” Susan Sontag, in her essay “Melancholy Objects” in On Photography calls photography “the only art that is natively surreal.” Photography renders the mundane extraordinary.

I don’t see Breton’s attempts at controlling and defining Nadja at work in Offen’s images of Grace and Grace’s world. Quite the contrary, in fact. Grace is presented throughout as a figure of mystery and, indeed, freedom, as she moves through and possesses these spaces. We, the viewers, are visitors, tourists in another realm. Allowed access only through the “unmerited favor” of the “deity” (to use McPhee’s phrasing) of this wilderness. The visit into this space leaves this viewer beguiled, entranced by the fleeting glimpse of the enigmatic world of Grace.

Contributing Editor Steve Harp is Associate Professor at The Art School, DePaul University

____________

Scott Offen: Grace

Photographer: Scott Offen (born in Boston, lives in Newton, MA)

Publisher: L’Artiere, Bologna Italy; 2025

Texts: essay by Laura McPhee

Language: English

Design: Teresa Piardi – Maxwell Studios

Hardcover with sewn and glued Swiss case binding with fall away spine exposing signatures; circular opening cut in cover with tipped-in image visible; 72 pages; 22,5 x 29cm; ISBN 979-12-809781-41

____________

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment