Review by Sebastian Boute and Matt Schneider ·

Thus, whether riding or walking, the process becomes about forms of reflection. Importantly, it is about the obstruction/mediation. Perhaps it is this kind of limitation that makes knowledge possible – that enacts a kind of deep inscription, if not a mapping, in the artist/writer/photographer/documentarian. And so, what are we to see and move through in the urban desert – this transect of life in this peculiar civilization? (pp. 12-13)

A Desert Transect, which is the latest photobook from sociologist and photographer Brian O’Neill, attempts to unpack everyday life and mobility in Phoenix through a combination of photography and ethnographic observation on the city’s monorail system. As we ourselves are ethnographers and visual sociologists, we couldn’t help but feel excitement as we turned through the pages. Through this project, O’Neill makes two contributions. First, O’Neill offers a glimpse into the process of ethnographic social science. In so doing, he considers the utility and potential of photography and suggests a method by which that potential might be achieved. Second, and more abstractly, after reviewing the book and coming together to discuss it, we found ourselves pondering a large but central question: “What kind of place is a city?”

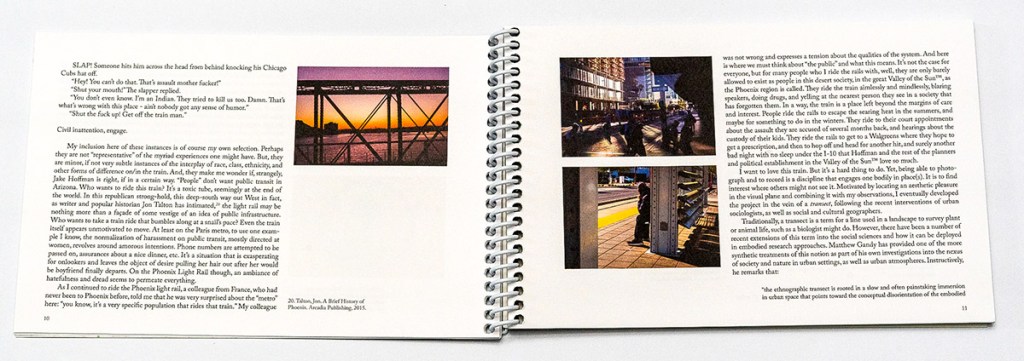

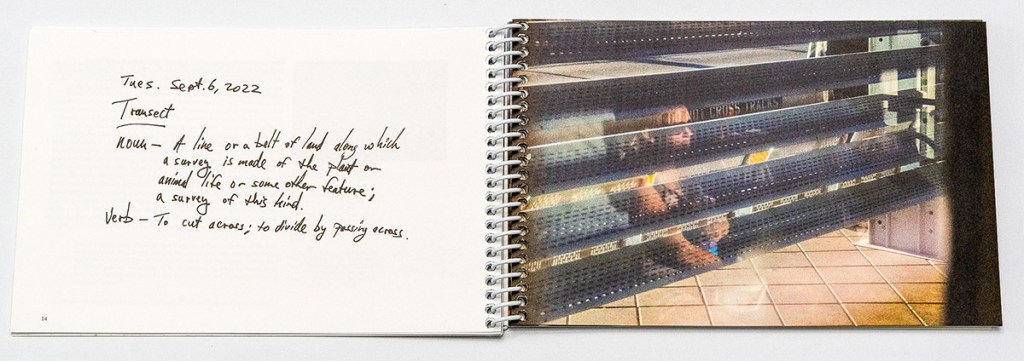

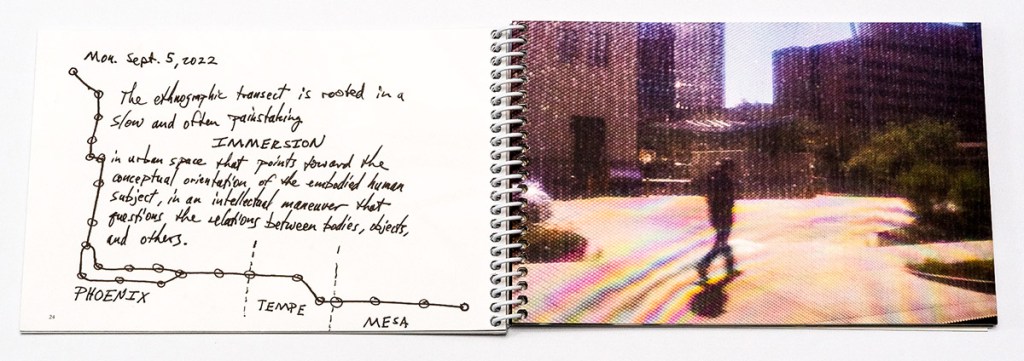

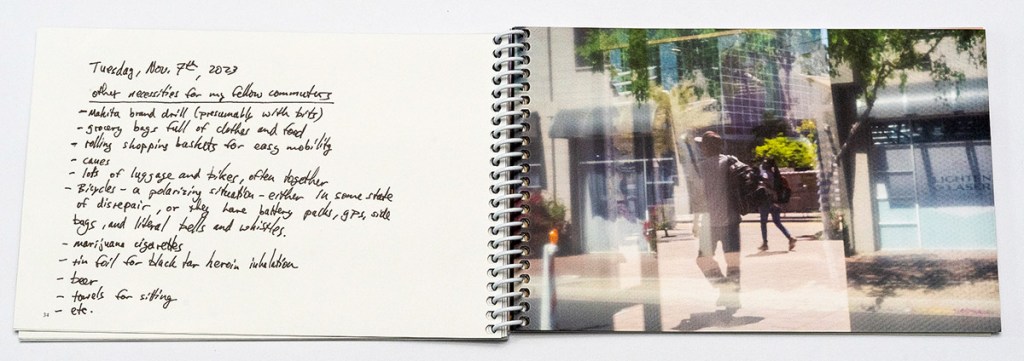

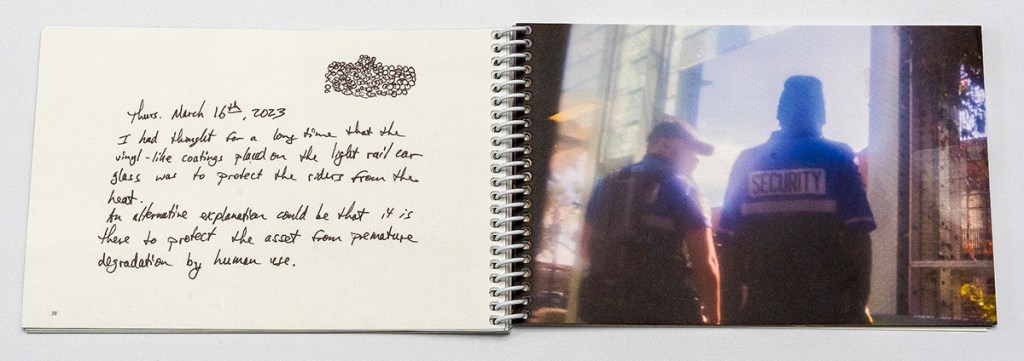

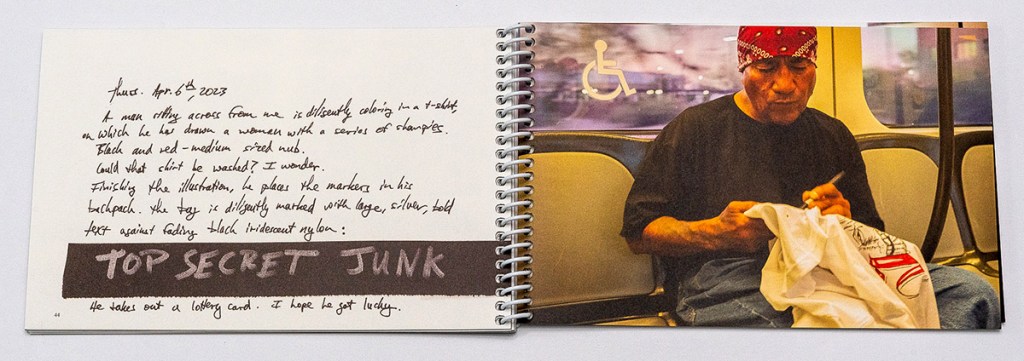

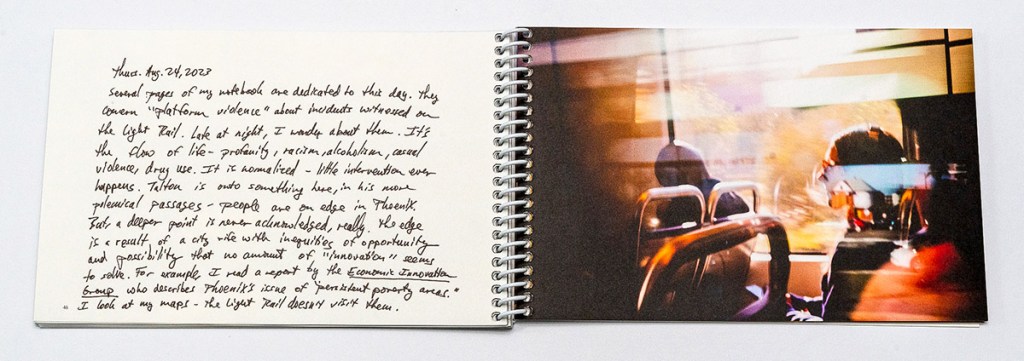

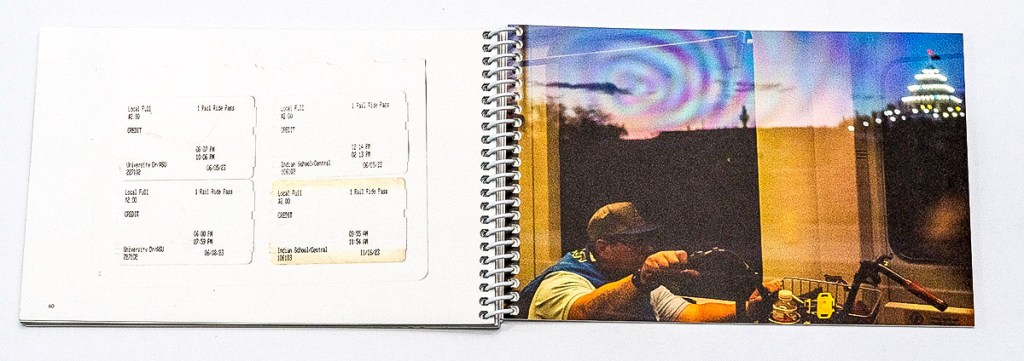

Our love for this book, in part, comes from the fact that O’Neill has found a way to present the process of social scientific observation in an effective and aesthetically pleasing way. Put differently, A Desert Transect’s design allows readers to see the steps of (visual) social science: observation à interpretation à transcription/note taking à analysis à production of social theory. As opposed to a standard academic essay, readers will find photographs and handwritten jottings – short, descriptive notes from the field about what the social scientist is observing, feeling, or interpreting in a given moment – that ultimately result in the typical long form essay and analysis that O’Neill also provides.

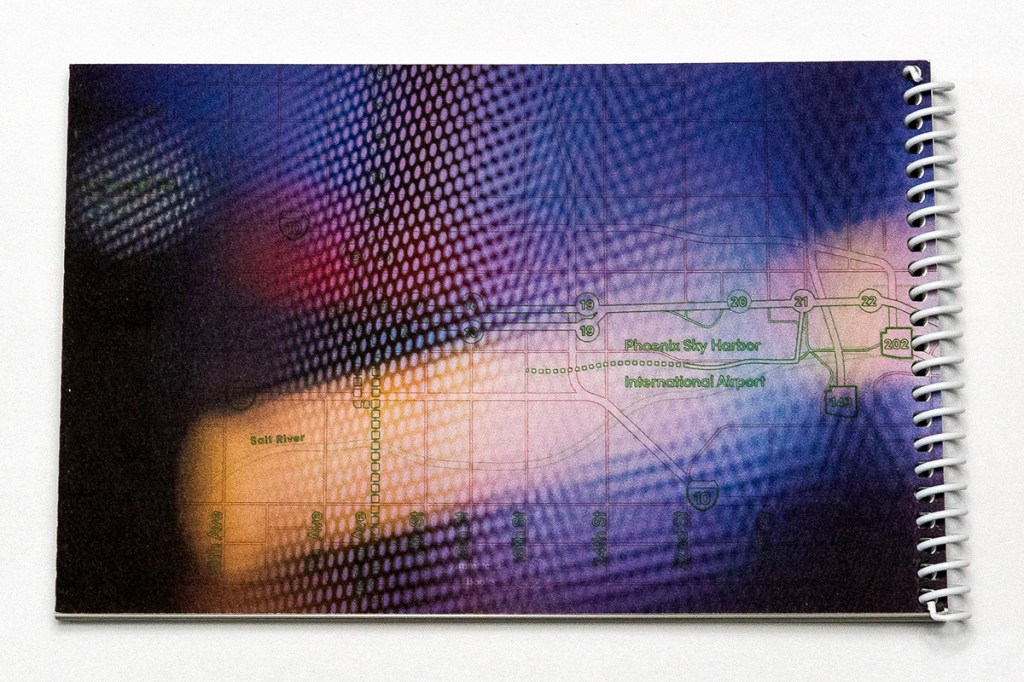

It is through this process that cities, and community life more generally, can be read from various vantage points, including the railcar. But, as O’Neill himself asks, “what’s the deal with photographing (on) trains” (p. 5)? Through an examination of Phoenix’s Light Rail System, O’Neill’s photobook focuses on mobility and public life in sprawling, often lonely, sometimes hostile, urban environments. For him, public transit represents a literal and metaphorical passage through urban social terrains. By observing the light rail, we observe the deeply socio-political dimensions of everyday public life. Using his camera as a tool to document and then contextualize these mobile spaces, he transforms what we would typically view as mundane settings and conditions into a narrative force – a public environment threaded through the Phoenix metro area and shaped by neglect and hostility. In this way, the photos provided are not simply to document. The photographs provide evidence of the social barriers that divide rail riders from other Phoenicians. Through visuals of city landscapes and individuals in transit, O’Neill uses the windows of the light rail to give his audience a glimpse into everyday life filtered, through – perhaps even skewed or obstructed by – heat resistant windows and the desert sun.

So again, the significance of O’Neill’s work, in part, lies in his commitment to document, move through, and care about ordinary urban spaces that might otherwise appear unremarkable – insignificant to our socially trained fields of vision. Thus, the work challenges readers to recognize the importance of observation and documentation as a means of encountering, representing, and dignifying the unknown, unseen, or overlooked social realities that exist regardless of their acknowledgement or neglect. By making the ordinary strange, the uncomfortable visible, and the sociological tactile, O’Neill’s project contributes to a visual sociology that is cognizant of the entanglements of urban infrastructure, metropolitan social life, and the aesthetic(s) it shapes.

So, through this process of observation, what kind of place does O’Neill find the city to be? Admittedly, O’Neill’s work forced us to complicate our own view of the city. Where we tend to see the city as a place of possibility and connection, O’Neill observes civil inattention. For example, he recounts one observed scene:

“Hey, any of you black guys learn how to be a black smith?”

SLAP! Someone hits him across the head from behind knocking his Chicago Cubs hat off.

“Hey! You can’t do that. That’s assault mother fucker!”

“Shut your mouth!” The slapper replied.

“You don’t even know. I’m an Indian. They tried to kill us too. Damn. That’s what’s wrong with this place – ain’t nobody got any sense of humor.”

“Shut the fuck up! Get off the train man.”

Civil inattention, engage (pp. 9-10).

Good young(ish) progressives, such that we are, it is not lost on us that our political position should dictate a wholesale embrace of public transit, which will aid in the fight against climate change, make the cities more navigable and accessible, and even encourage personal fitness through pedestrianism. What’s not to love? And yet, as O’Neill notes, “love[ing] this train” is “a hard thing to do” (p. 11). A Desert Transect calls our attention to the ways in which such conversations paper over the very real classed, gendered, and raced dimensions of public life and public transit. By framing the Phoenix Light Rail not only as a means of transportation, but as an enclosed space of inattentive civility, O’Neill reveals these spaces as grounds for social friction, and even suggests that it is in spaces such as these that we learn to overlook social conflict.

A Desert Transect is a wonderfully thoughtful and meticulously composed work of visual ethnography. Though clever uses of desert and railcar lighting, O’Neill maximizes the film-like, nostalgic quality of images captured by Fuji Film cameras, but more importantly, provides a model for bridging art, documentary, and social science. The intertextual engagement between theory, ethnography, and critical observation, all enclosed within its 8.5” x 5.5” rectangular pages, make for a thought-provoking reading experience. Further, the book presents a satisfying blend of material styles, including, on the one hand, a spiral binding that invokes the field-based nature of the project. On the other hand, the book is printed with high quality materials, including matte archival quality pages that make the reader feel as though they are holding a valuable artifact that would more appropriately belong to a museum or gallery than to personal library.

Regrettably we must report that at the time of writing, A Desert Transect is already sold out on the publisher’s website. We suppose it’s possible that Immaterial Books will run a second edition, as they have for other popular titles. But if not, we are, at the very least, pleased that this work can be consumed in a variety of other mediums that are freely available. For example, O’Neill has published the book’s main essay under the title “Riding in the Desert City” at AnimaLoci, and Immaterial Books has produced a 35 minute music video featuring O’Neill’s photos and videos set to the music of Wyoming Toad. We strongly urge anyone interested in street photography, documentary photography, or visual sociology to seek out these thoughtful and compelling works.

Sebastian Boute is a master’s student in the Department of Sociology and Criminology at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington.

Matt Schneider is a professor and visual sociologist in Wilmington, North Carolina.

PhotoBook Journal previously reviewed Brian O’Neill’s Beach Boulevard.

Disclosure: Brian O’Neill is a frequent contributor at The PhotoBook Journal, and the authors of this review know O’Neill personally. Schneider and O’Neill have co-authored academic works, and they have spent many a day traversing urban landscapes with their cameras.

____________

Brian O’Neill – A Desert Transect

Photographer/Author: Brian O’Neill

Publisher: Immaterial Books, copyright 2025

Design: © Alex Wilk

Images + Text:© Brian O’Neill

Spiral Bound; 8.5” x 5.5”; 120 pages; edition of 100; ISBN:978-1-962415-09-5

A full discussion of the book project can be found on Immaterial Voices

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment