Review by Steve Harp ·

It takes time for what has been erased to resurface.

- Patrick Modiano, Dora Bruder

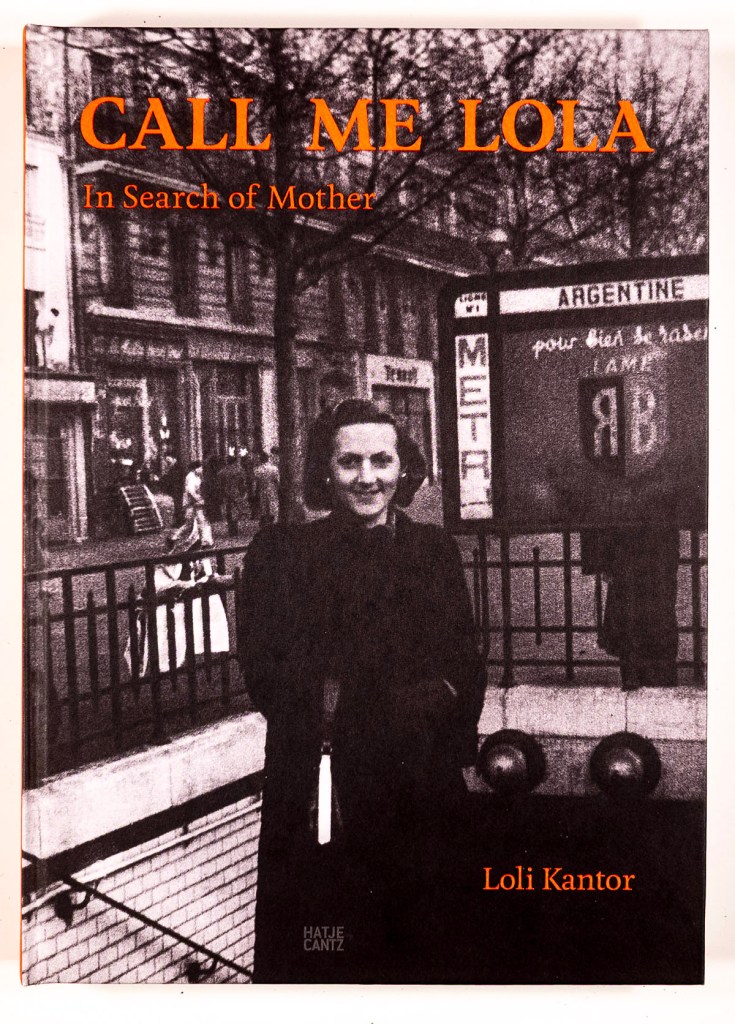

Loli Kantor’s Call Me Lola: In Search of Mother has been obstinately staring at me from my desktop for some weeks now. At each encounter, I would fitfully and clumsily try to find a way into thinking about this book, a way to do justice to the story, the images, the unsettling hauntingness of this volume that, although offered as a photography book, I can only think of as something else entirely – a memoir, a detective story, a search for a mother never known who died scant hours after the photographer/memoirist/detective’s birth. The difficulty this reviewer has encountered in finding a way into writing about this tragic yet compelling story can only suggest in the most minimal way the journey of the photographer in her pursuit of finding her mother.

Hovering over my encounter with this book has been the ghost of Dora Bruder, a short work published in 1997 by Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano. Dora Bruder tells the story of his search, prompted by a short notice found in a 1941 copy of Paris-Soir:

Missing, a young girl, Dora Bruder, age 15, height 1 m. 55, oval-shaped face, gray-brown eyes, gray sports jacket, maroon pullover, navy blue skirt and hat, brown gym shoes.

The book traces Modiano’s investigation, more than 50 years after the fact, to solve the mystery of Dora Bruder, to “find her” or at least find something about her. Nothing definitive is discovered, nothing to dissuade the searcher from the inevitable conclusion that Dora Bruder ultimately found her way – as did so many other Jews – to Auschwitz. As Modiano writes at one point:

I send out signals, like a lighthouse beacon in whose power to illuminate the darkness, alas, I have no faith. But I live in hope.

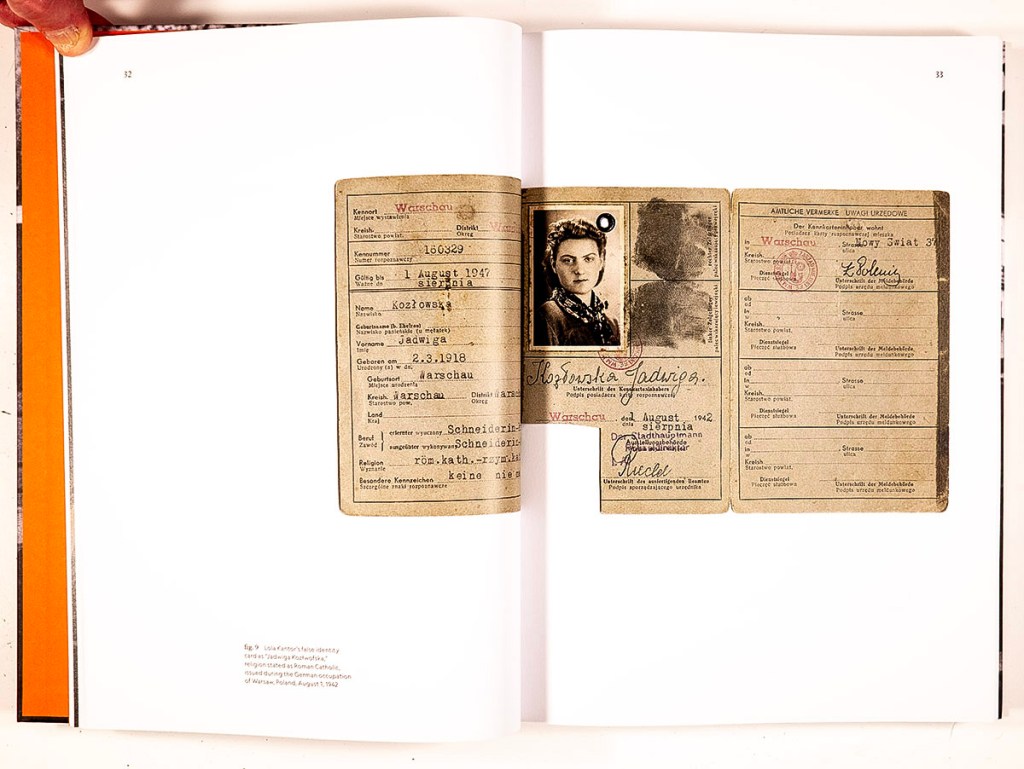

This might describe Kantor’s quest as well. Although Kantor’s mother, Lola, survived the war (by assuming a false identity as a Roman Catholic) one can only understand Lola’s untimely death (and her daughter Loli’s resultant loss) as another consequence of the “destruction of the European Jews” (to use the title of Raul Hilberg’s pioneering study of the Holocaust).

The book opens with an insightful and provocative introductory essay, “Becoming Lola,” by Nissan N. Perez, a photography historian, researcher and curator based in Tel Aviv Israel. In it, Perez remarks on Loli’s photographs of her mother as “evidence of loss and . . . absence,” elusive images giving rise to “the artist’s imagination, interpretations and fantasies.” Lola “remains an elusive and mysterious figure . . . a ghost image. . . “

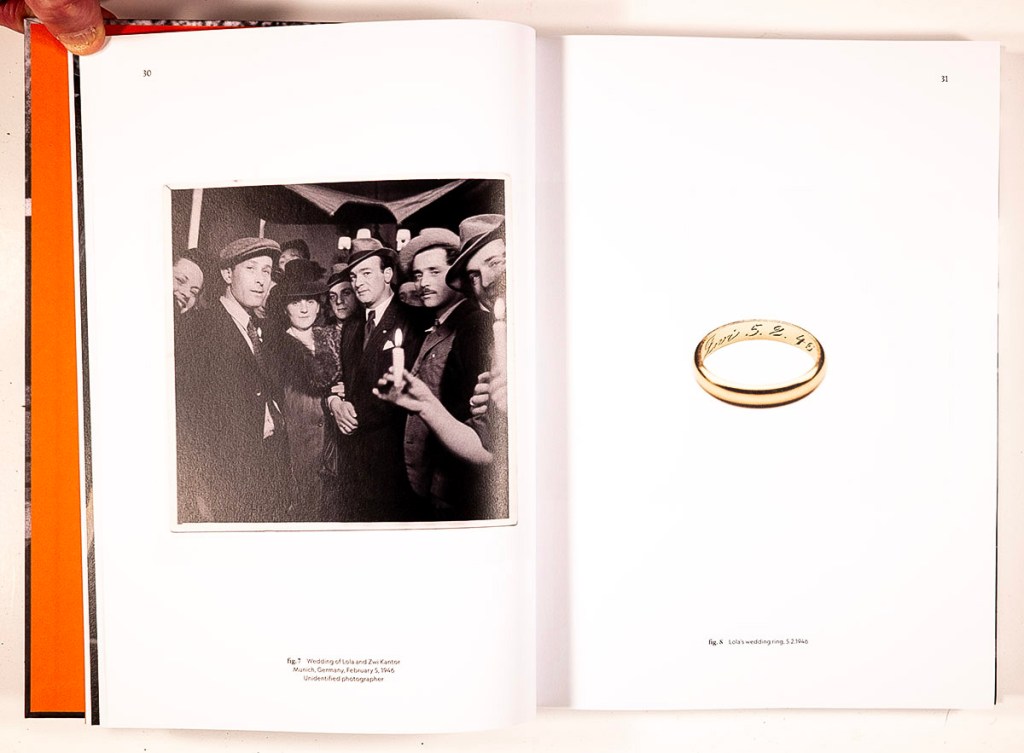

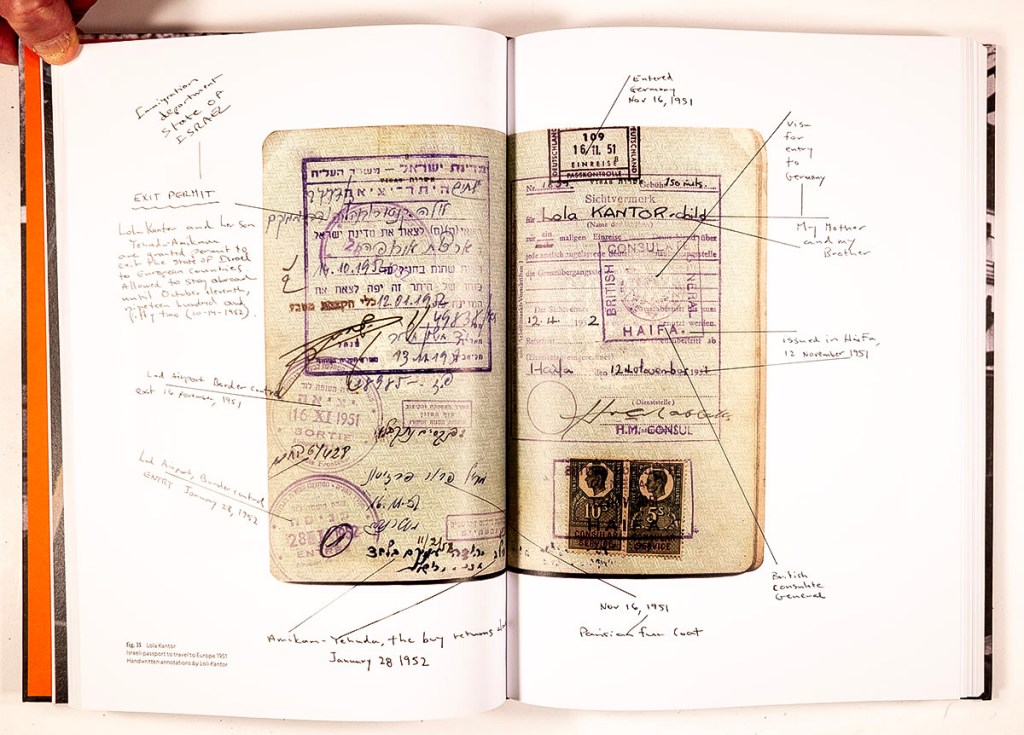

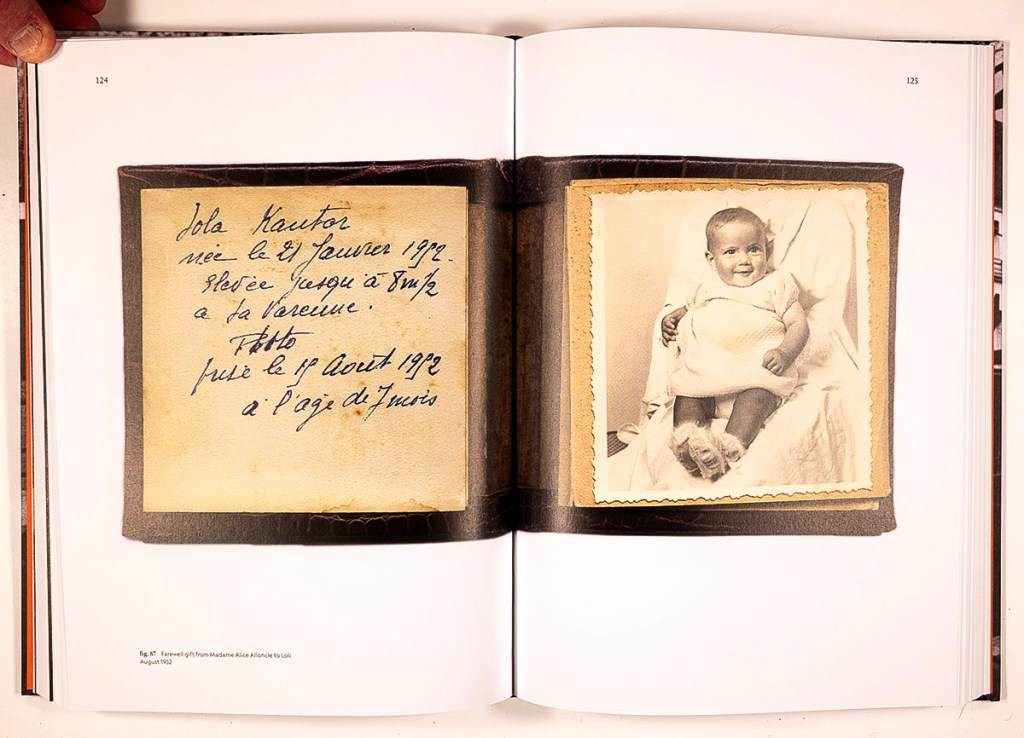

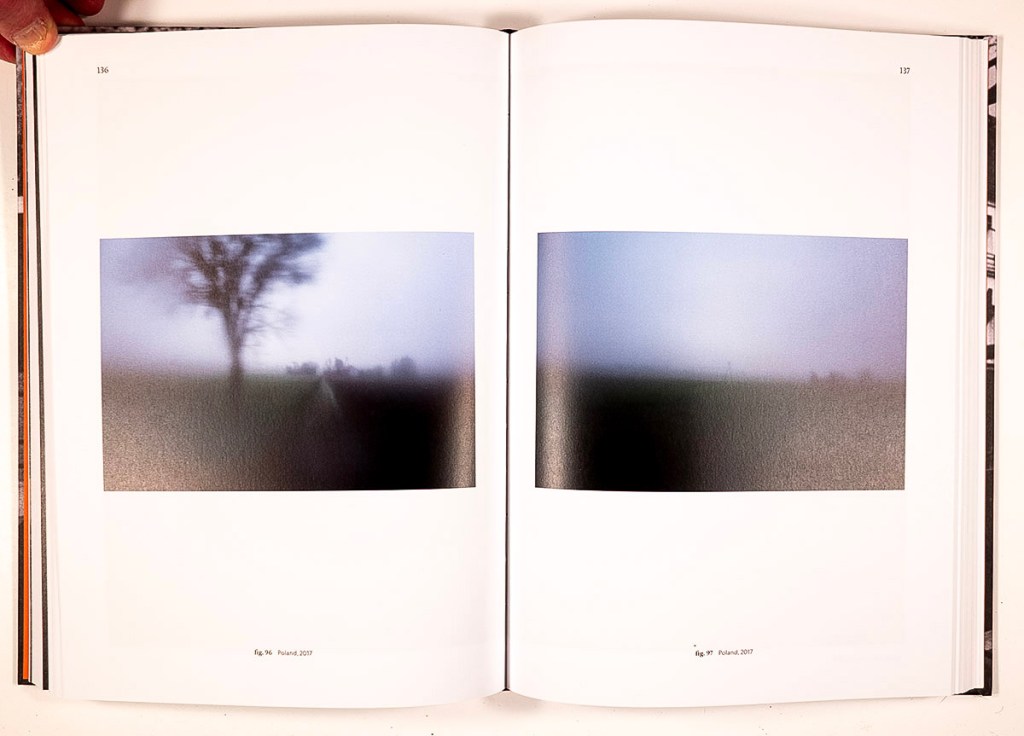

The book functions as a kind of archive of Loli’s investigation to find her mother, who vanished so soon after giving Loli birth. The 159 figures printed therein include historic documents (official as well as journalistic and familial), photographs of physical objects (Lola’s wedding ring, a powder compact Lola had among her possessions during her fatal hospital internment, a Bat Mitzvah gift to Loli and other assorted “memorabilia”), photographs historic and archival as well as more contemporary photographs Loli took between 2004 and 2023 as she traveled throughout Europe and Israel, tracing the movements of her mother’s life leading to her death (and Loli’s birth).

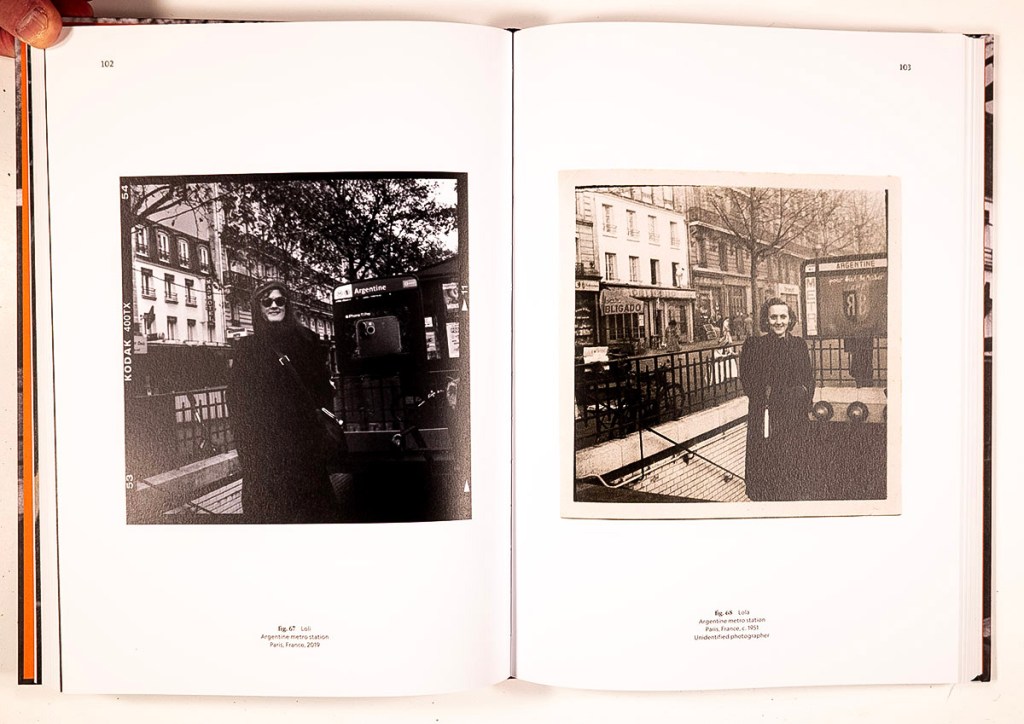

Significantly, much of the archival material – documents and family photographs – are not presented simply as facts or “data,” but as physical objects as well. Borders of photographs are included, photographs are presented displayed in frames, Loli’s birth certificate is presented as crumpled, taped, written on; a collection of newspaper clippings is shown in the spiral binder into which they’d been affixed since 1952. While the images in photographs may not age, photographs as objects do. Certain photographs are fragmented, blown up to bring attention to specific details within the image (figs. 156, 157). And Loli’s contemporary photographs are not simply documents of places Lola had once inhabited, but many are a kind of fantasy restaging of Loli in the same place as Lola (pp 102-103) or Loli in the same type of dress as Lola (pp 105, 162).

These visual strategies testify to a relentlessness in her pursuit of finding her mother, a complex relationship between photography and memory, a “partially fractured knowledge” as Perez writes in his introductory essay. Despite the number and variety of images Kantor gives us in this gripping and captivating volume, what will never be accessible to us, what will never be reachable to Loli, is the figure of her mother. All photographs can ever do is point to absence and loss and Call Me Lola demonstrates that eloquently.

The book ends with an interview of Loli Kantor by Danna Heller, a London-based curator and art historian (who also so happens to be Kantor’s daughter). In the interview, Heller explicitly makes reference to “discoveries . . . made with a detective’s eye,” a kind of “studying for clues.” To which Loli admits being attracted to the “enigma of not understanding,” coming to view her mother as an absence. To consider this book simply as a book of photographs or as a monograph would be misleading. Heller introduces the interview by commenting on Loli’s ability to “exist in the past and the present at the same time.” An apt description of photography itself. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes remarks on photography being a “collection of tenses.” Loli approaches her photographic investigation as a gathering of clues, evidence. As is the case with all photographs, central to their [very existence] is their existence as indexes: traces, remainders, residues. Always pointing at something . . . but what?

Contributing Editor Steve Harp is Associate Professor at The Art School, DePaul University

Loli Kantor – Call Me Lola

Photographer: Loli Kantor (born in Paris, resides in Fort Worth Texas)

Publisher: Hatje Cantz, Berlin Germany; 2024

Text: Nissan N. Perez (essay), Danna Heller, Loli Kantor (conversation)

Language: English

Design: probsteibooks (Sabine Pflitsch, Andreas Tetzlaff)

Editing: Loli Kantor and Nissan N. Perez.

Printing: Westermann Druck Zwickau GmbH.; Zwickau, Germany

Hardcover with case (sewn) binding; 232 pages; 8” x 11.25”; ISBN 978-3-7757-5774-4

____________

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment