Review by Brian F. O’Neill ·

There has been a surge of image-text photobooks in the market in recent years. In some, the texts and images operate rather independently, while perhaps still holding onto some underlying issue. In others, the text is treated as an opportunity for a more traditional analytical “lens” on the subject matter or phenomena in question. In still others, the images and texts seem to have no obvious or underlying relationship, which sometimes can be meant to allow one to unpack or reintegrate some of the fundamental ambiguities of lived realities into the hybrid viewing/reading experience. Arturo Soto’s 2025 book, Border Documents is his latest contribution to the image-text genre, producing a work that utilizes conventions and techniques that blend the practices of documentary photography and cultural geography in terms of his concerns about place, emotion, memory, and collective experience. To its credit, the project also offers a departure from so much photographic work conducted in and around the U.S.-Mexico border, as the book is sincere without being sentimental, incisive without being dramatic.

Border Documents is published by The Eriskay Connection, who also published his prior works, A Certain Logic of Expectations, and In the Heat. The book’s images are all monochrome, with an assemblage of photographs on the inside of the cover flaps. And indeed, the exterior elements are a useful place to begin understanding this work.

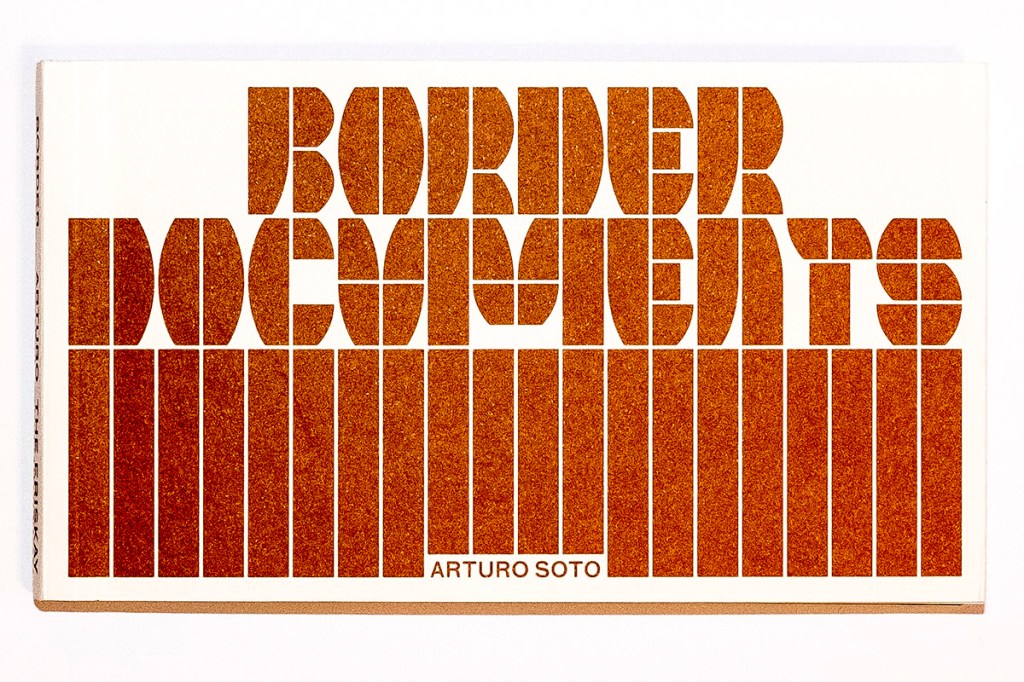

The book has been attractively designed by Rob van Hoesel. The cover is striking, gaining its full force when the entire book is propped open: terracotta colored text in a unique take on a stencil font is overlaid on a tan background. The simple, bold typographic choice is enhanced by the underling sequence of rectangles. Connecting the elements of the stencil design are tan gaps, reminiscent of the gaps one can look through between the U.S.-Mexico border wall. The aforementioned cover flaps contain a series of identity card photos of Soto’s father, also named Arturo, signaling the connection that is developed throughout the rest of the book. While the design is striking, the size of the book itself is also striking for its small size at 165 by 95mm (144 pages). The book is, appropriately though, just a little bit larger than a passport. Unlike a passport, the book’s signatures have been sewn together in a layflat design providing a pleasurable reading and viewing experience, and as such, the intimacy of the object parallels that of the text the reader encounters.

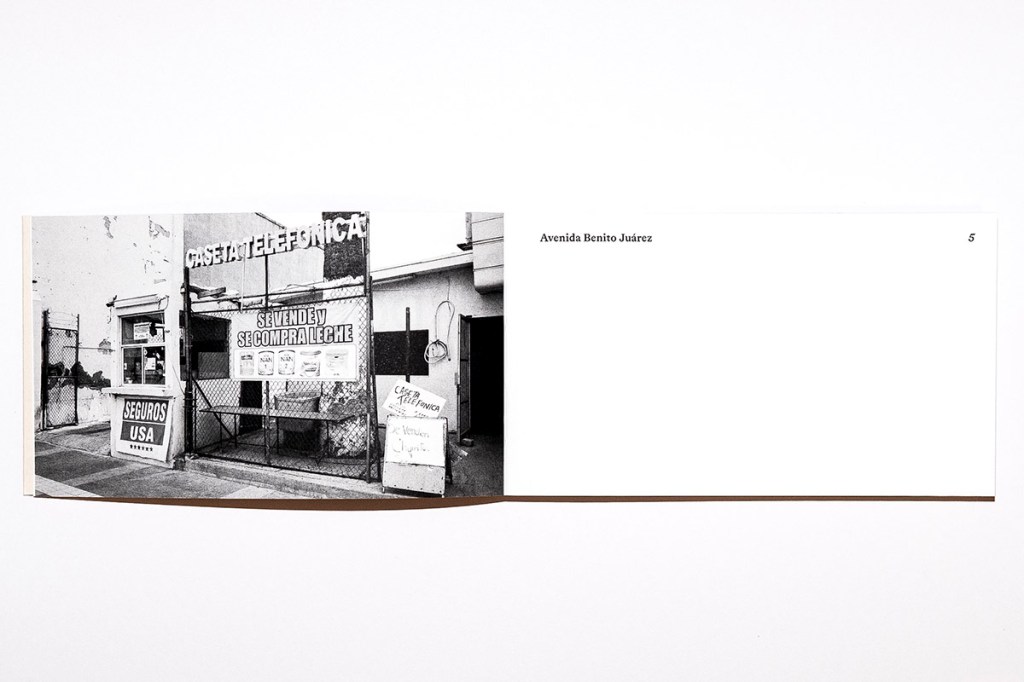

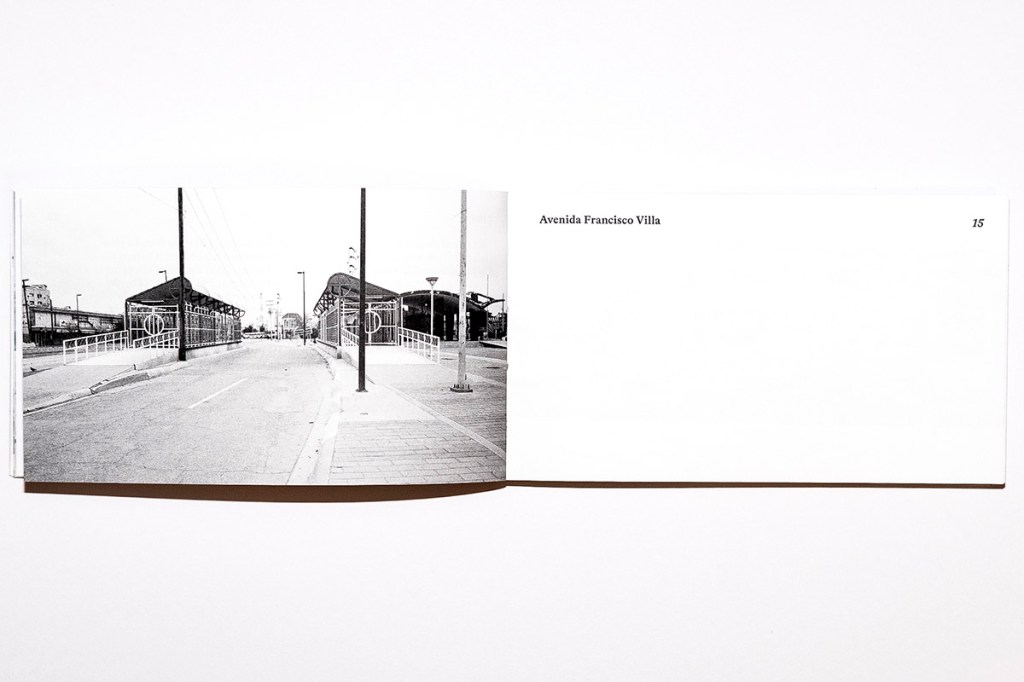

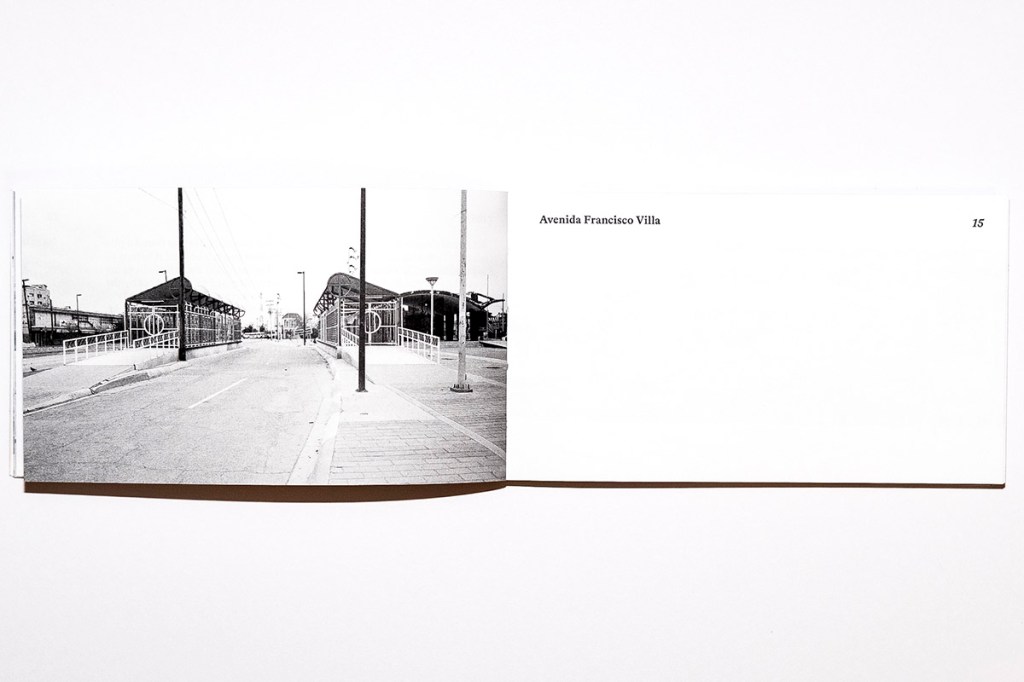

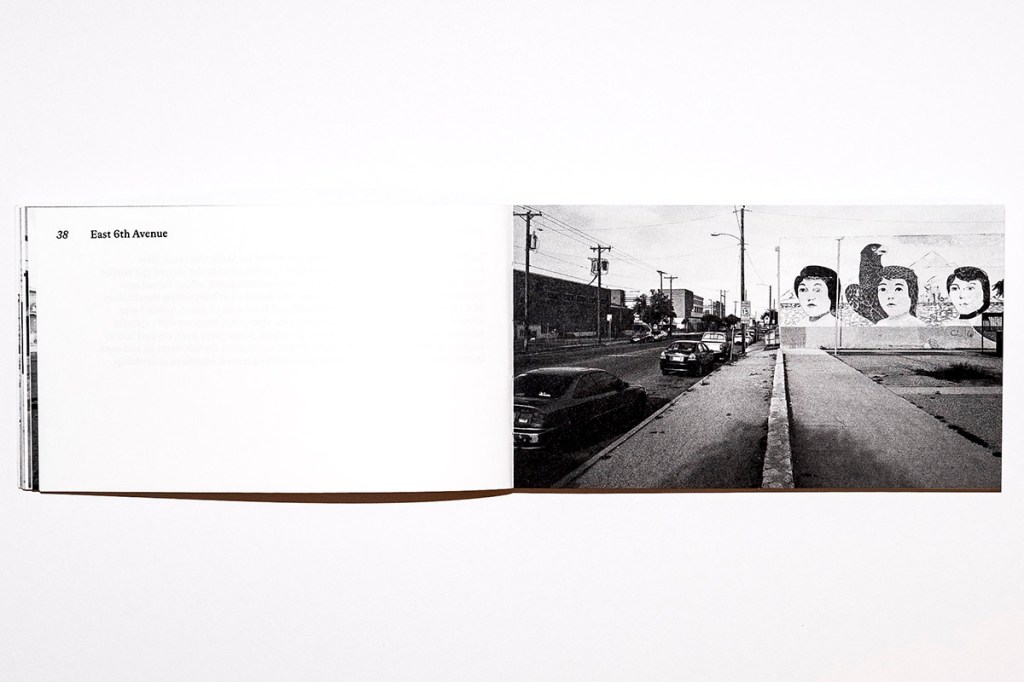

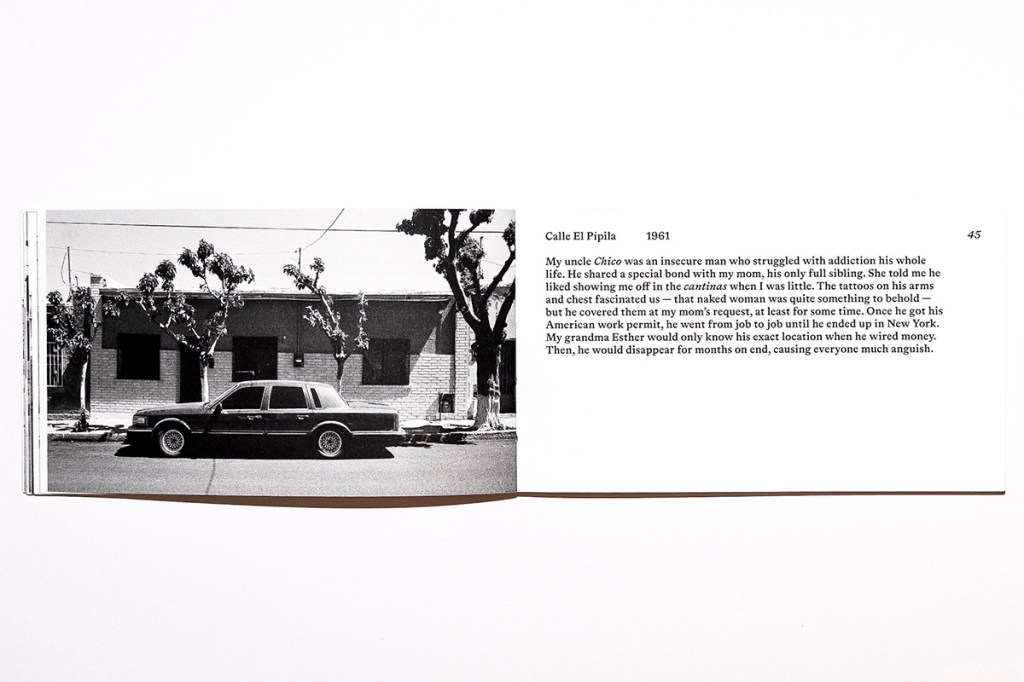

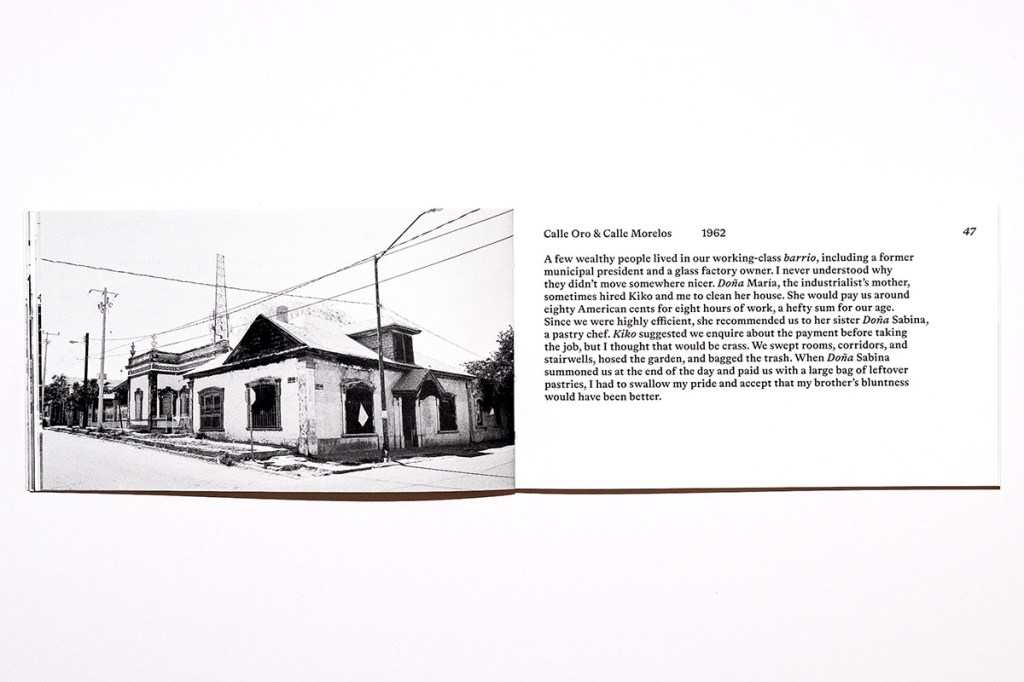

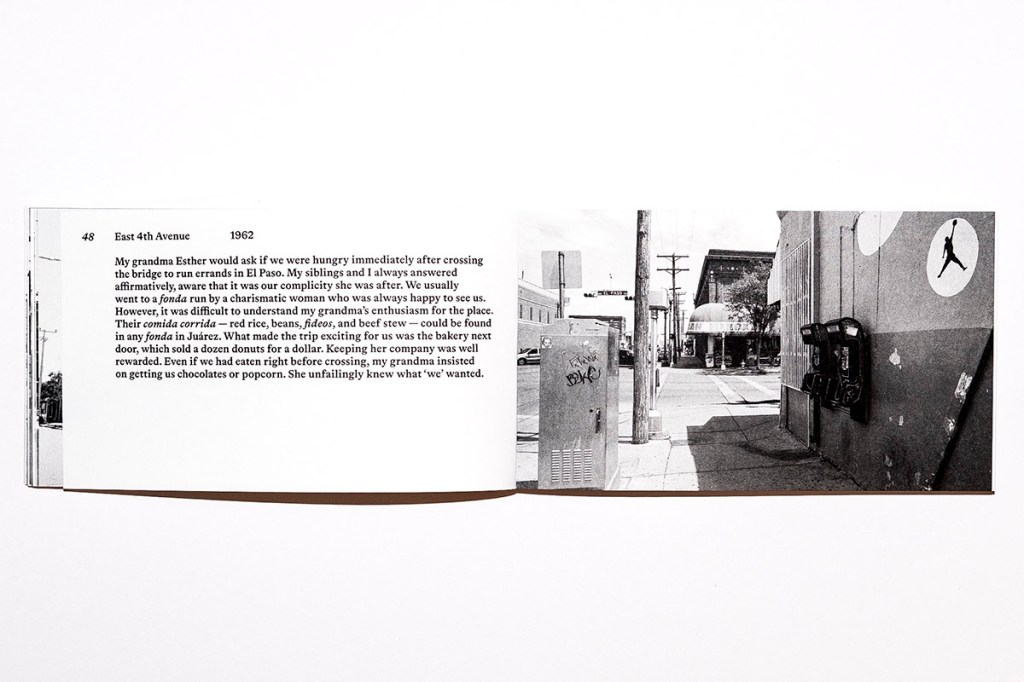

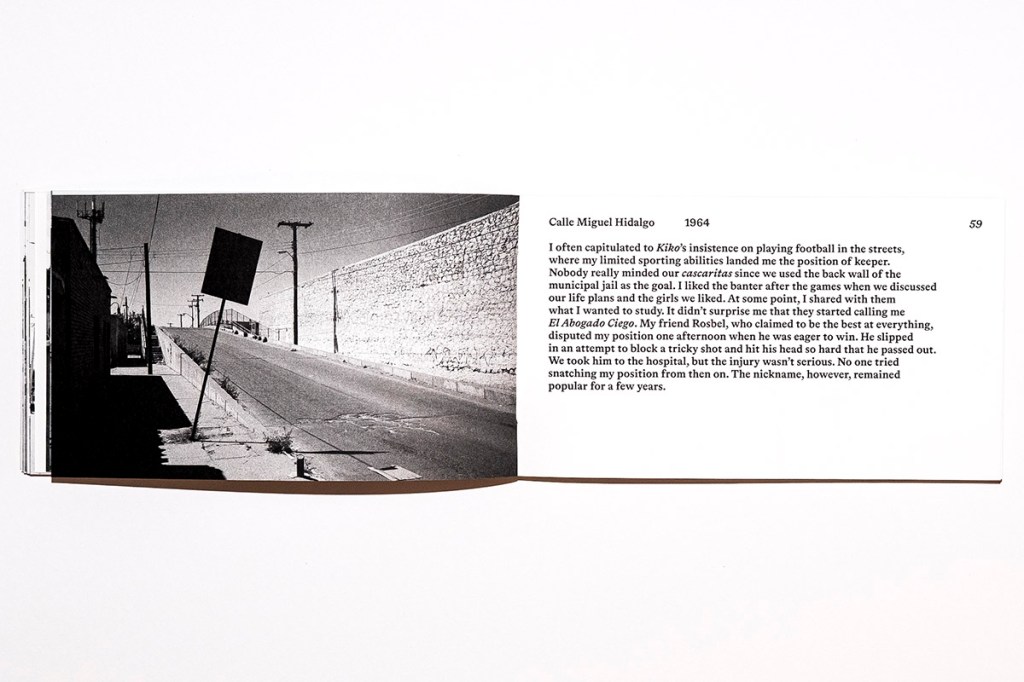

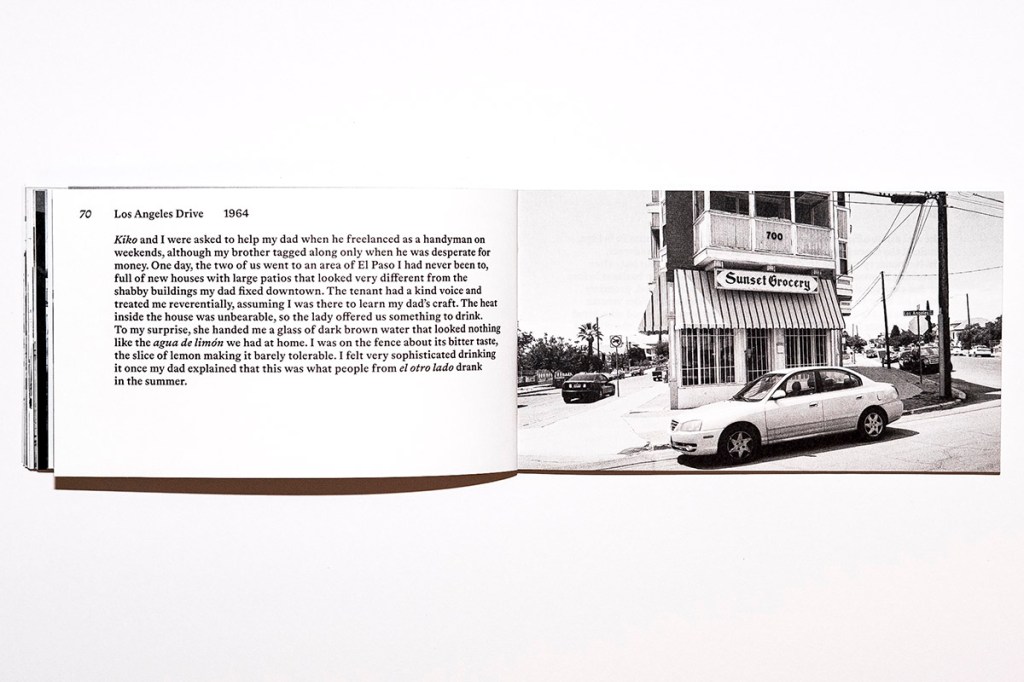

Throughout, the writing and images are complimentary. As in Soto’s other works, the images are precise, “straight” photographs. They are, quite literally in this book, street photographs, but not in the sense of much street photography. Yet, the images remain accessible given their concern with vernacular spaces, architecture, murals, and everyday objects. Additionally, the way the images are framed by Soto coheres with the overall idea of a progression through time, as many of the images are of paths, walkways, and sidewalks. Border Documents is not a book of artifice or clever camera work, per se. What it is, is something resembling life: eye level and on the street, connecting with people and things, and in so doing, the book brings the images and texts into conversation at the level of what it means to live and be in the places that we remember and depict.

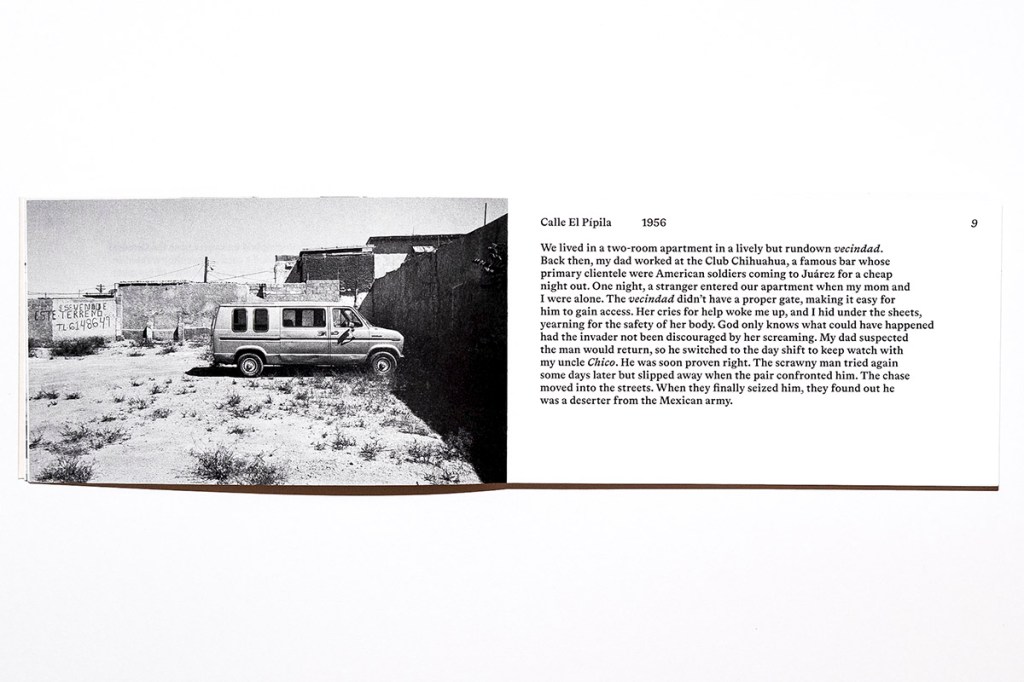

While Soto made the photographs in 2016, the story of the project begins in the early 1950s. The family archive of images and documentation that Soto has utilized are labeled with dates, differentiating them from his own pictures. The project is the result of the author collaborating with his father, as the texts are built up from a combination of conversations and written accounts by his father, which Soto reworked over time and made succinct for the purposes of this book project.

As the reader moves through the text, the astute viewer will be able to detect the fact that the images and stories take place on both sides of the border (although, perhaps tellingly, it is not always easy to differentiate). Sometimes signage in English or Spanish is a give-away to the location, but Soto has smartly sequenced the images so that the locales meld together. We see a street with a mural of an eagle and three women, elsewhere there is a sunlit avenue with its electrical lines running from wooden poles hovering over a Dodge Stratus, and further on, homes and business with gates and bars protect from theft and vandalism. We visit Sunset Grocery on Los Angeles Drive, and the Camino Real Hotel on North Santa Fe Street in El Paso, just as we do the Avenida Abraham Lincoln in Ciudad Juarez. The ability of the photobook to collapse space and time is performed beautifully here. While Soto’s images move between places and moments, the images are not a photojournalistic account of crime, the decline of border towns and the other well-known dimensions of life there, which are very real, but also exploited by the media and political elites to varying degrees.

While Soto’s images are made and presented in a way that emphasizes their facticity, and with a normal field of view similar to what the human eye might take in, Soto’s lens is used to take the viewer, in a sense, along for the ride. No dramatization needed. This visual language is more generally characteristic of Soto’s work, but unlike his other projects, Border Documents is the most personal to date, as he explores his, and his father’s proverbial backyard. To his and the book’s credit, the straightforward approach to the images encourages second viewing, enabling the reader to contextualize the images in relation to the written texts.

In this vein, Soto takes seriously how personal biographies are tied into larger global histories and forces, an aspect that is especially reinforced as the reader comes to understand the life history laid out in the text. Still, the image-text combination is important, as the images manage to comment upon the larger social transformations that have shaped the border without being overly didactic. In one particularly striking image that gives the reader pause, a man rests in the midday sun on a traffic barrier. Barbed wire runs along the top of a tall stone and cement fence. To the right, a ubiquitous white plastic encased surveillance camera collects footage of the surroundings. An American flag blows in the wind as people collect groceries. A picture of Pope Francis waves in the distant horizon. In the center of the frame, an UETA DUTY FREE sign, in Spanish, advertising liquor and smiles looms large. Life on the border.

Despite physical, legal, and other barriers, there is, and has always been a fluidity to life in this region, suggesting movement, gaps, and continuities, all of which are further manifested in the book’s internal design. While many of the images are accompanied by texts, this is not always the case. Sometimes images are simply identified with a placename. At other moments, a short text is all that is supplied next to a blank page. For example, we learn that passersby would be photographed unawares near the Juárez Cathedral and given a card asking if they wanted to buy the picture. Yet an image is withheld from the viewers/readers. We read on, as the elder Soto explains, he remembers a moment of this happening and holding his mother’s hand: “I can’t recall the moment it was taken, but I remember failing to identify myself when I first saw it: a picture of my mom and a little stranger, I thought” (p. 7).Photography, of course, in its supposedly evidentiary qualities, can also sometimes confound our perceptions.

Holding the tensions of the region together but also concerned with the way photography and text function are real strengths of Border Documents. In particular, time is constantly evoked through the project. On one level, this is interesting because of the often-mentioned fact that photography seems to withhold time, due to its (often) split second nature. But the progressing dates and the texts always remind the reader of the passage of experience. Yet, to the work’s credit, this is never overly sentimental either, and in fact, the book subtly traces the transformation of the region. Where the early texts speak of situations that may be common to many in the period, such as a first-time viewing television in the 1950s (p. 19), the vignettes slowly shift in their concern towards an accounting for the more generalized affect that seems to encompass parts of the region in ways that we may be more familiar with today: apprehension, if not fear. Yet, the text still stays true to its personal qualities. By 1981, in the last vignette of the book, the elder Soto expresses anxiety about the future for his family, “wanting to shield my newborn son from the vices and limitations of Juárez that had ruined the lives of many loved ones” and about the expanding role of the American Empire in “the desert” (p. 139). In this moment of personal transformation for the elder Soto, of a move to a new city to practice law, of a new son, we feel deeply human anxieties so many of us share and it is in this way that the book closes its portrait of life, important and consequential on its own terms.

Typing in “border documents” into a search engine, one of the first links you will encounter is, not Soto’s book, but a U.S. Customs and Border Protection page, detailing the type of documentation one may need to carry with them, depending on the type of travel in which one may be engaged. However, with Soto’s Border Documents, we see a positive subversion of this idea, collected here in a series of images and stories that also are carried and embodied, and going further, even reordering the reader’s sense of perception about the US-Mexico border. Seen in this way, Border Documents challenges the reader to see through the cracks in the apparent monolith of “The Border.” Amidst the contemporary wave of image-text photobooks, Soto’s books stand out for their rigor of execution, discernment in subject matter, and consideration for relevant themes, both humanist and political.

Brian F. O’Neill is a photographer and sociologist based in Phoenix, Arizona.

PhotoBook Journal previously review Arturo Soto’s A Certain Logic of Expectations and In the Heat.

____________

Arturo Soto – Border Documents

Photographer: Arturo Soto (born 1981, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico; lives in Los Angeles.)

Text: English

Publisher: The Eriskay Connection, 2025

Design: Rob van Hoesel

Printing and binding: Wilco Art Books, Netherlands

Softcover; Otabind layflat binding; 165 X 95 mm; 144 pages: ISBN 978-94-92051-72-1

____________

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment