Review by Brian Arnold ·

Imagine, if you will, a couple stripped down to their underwear, together leaning against a tree along a lakeside beach in Cheryomushki, Siberia. It’s hard to determine the variety of tree but it bends like it was designed to cradle the woman. The couple looks a little intoxicated, giving the scene a Dionysian feel of a beach holiday. The woman looks us in the eye holding a hardboiled egg, as if she’s offering it to us, tempting us to join the party; wearing only a soggy bra and panties, this token has clear sexual overtones. The man, his finger perfectly illuminated by a sun beam falling between the canopy of leaves, points to something just outside of the frame. Together they look free and comfortable, delighting in one another’s company and sexuality.

This picture, found in the new monograph of Nikolay Bakharev, Cheryomushki, is one of many that describe lakeside social life in a factory town in southwest Siberia in the early 1980s. I was a teenager in the 1980s, the Reagan years, and remember this as the height of the Cold War. Regularly we were inundated with rhetoric about the evils of the East, communism characterized as an existential threat to our civilization. Reagan also funded a proxy war against the Soviet Union, supporting the mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, those crossing over from Pakistan while they waged jihad (many of them later forming the core of the Taliban). These fighters were relentless and ultimately proved to be the demise of the USSR. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, it completely shifted the global dynamic. I do have one distinct personal memory about the Berlin Wall; I took my first trip to New York City in the spring of 1991 and when walking up 53rd for a visit to MoMA, some bank or corporate headquarters proudly displayed a chunk of the wall outside their front door, a monument to the supremacy of capitalism.

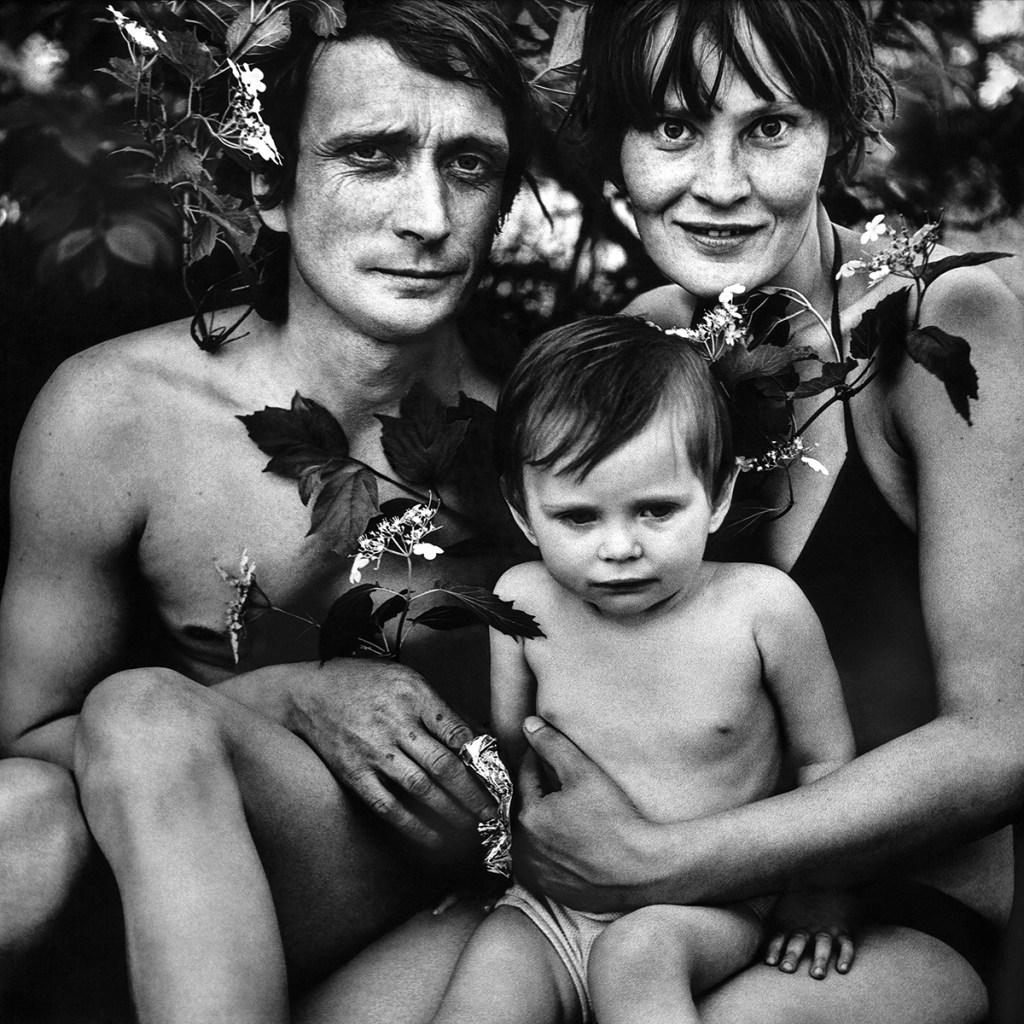

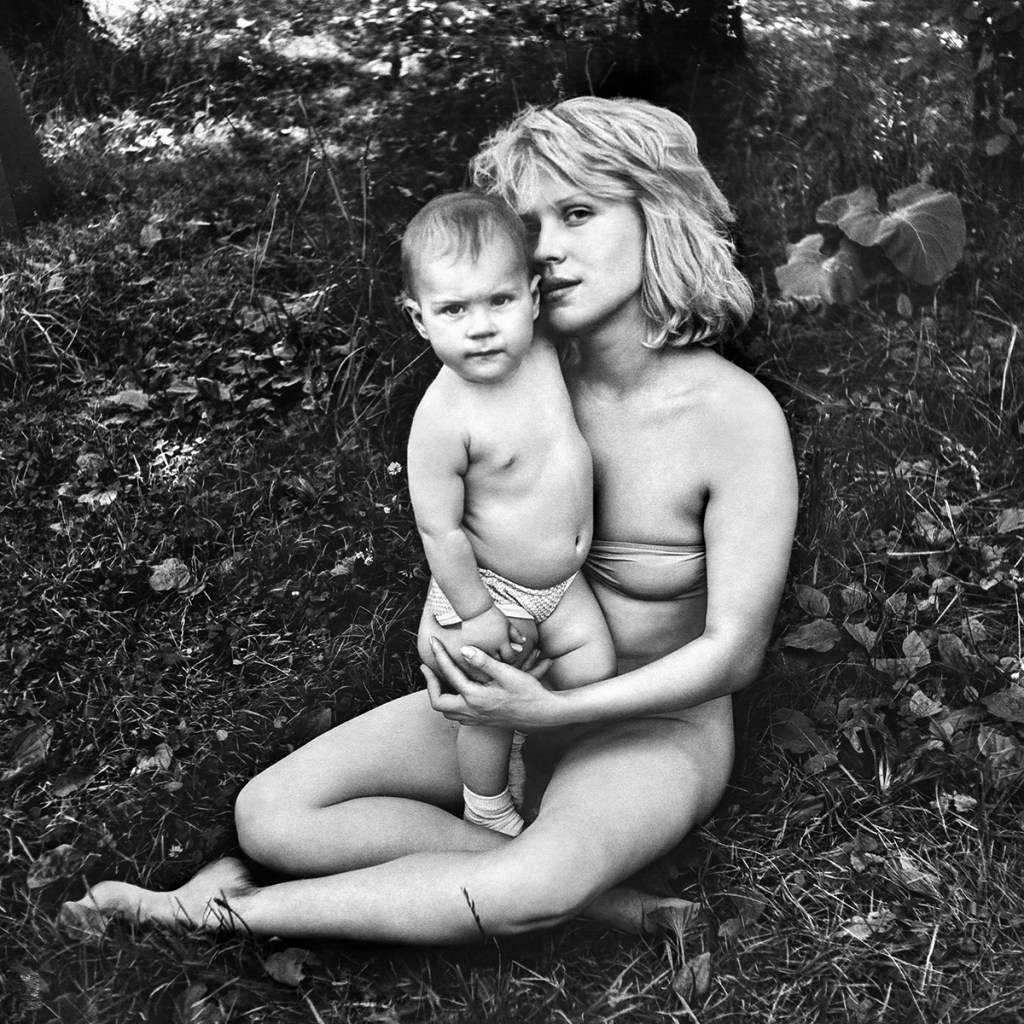

None of this is to say that I understand anything about life in the Soviet Union these years, but it is easy to imagine it difficult – the country stretched thin by war, and the people dominated with strict media and censorship protocols. Bakharev’s photographs in Cheryomushki are of an anomaly, pictures of ordinary people not authorized by the state, often in their underwear, and there to seek pleasure and to find freedom (if only momentarily) from their political identities. With his portraits, Bakharev photographed people who clearly know pain and suffering, who know the realities of hard, thankless work, but shows this isn’t really what defines them. Like people all over the world, it’s the little things that make life, and here we see people finding elemental joy. These pictures are a bit sweet but also full of contradictions, and this is precisely what makes them so compelling – they are clandestine, even illegal, but also intimate; simply composed but richly layered with personal and cultural history; and equal parts humble and profound.

There is very minimal text in Cheryomushki, but it provides essential background information for the pictures:

Nikolay Bakharev grew up in Soviet Siberia, where artistic expression was strictly regulated. Orphaned at four, he was placed in state care, where he first discovered photography. He was later assigned to work in a steel factory in Novukuznetsk, a Siberian city shaped by its metallurgical industry…As the USSR began to unravel in the early 1980s, he turned to private portrait photography, traveling to nearby rivers and lakes, where workers and families spent their free time.

Imaging the people in these photographs working in industrial furnaces forging the steel needed for the Soviet engine adds an important element to the pictures, as does knowing that Bakharev was orphaned and a warden of the state (broken and forgotten souls often discover real empathy). These photographs are really quite humble – adequately crafted (I’d venture a guess the book plates are better than his prints, his materials would have to be tightly rationed), composed in the most basic ways (the subject almost always in the center of the frame), and again proving that photography is at its best when simplest, no gadgetry or tricks, just clear pictures. Looking through these photographs, I feel moved to care for these people as my own family, friends, and neighbors, our lives undeniably similar.

In describing the Communist Bloc, Reagan got a lot wrong and completely failed to make a distinction between the people and their governments. The people in these pictures are just like you and me – worried about money, wanting the best for their children, relishing sunny days, and finding solace with friends, family, and lovers. Reagan wanted me to fear and despise this culture, but hating these people would be like hating those found in Disfarmer’s photographs, because like those he photographed in Herber, Arkansas, these photographs from Novukuznetsk, Siberia represent ordinary working folks, and are made with empathy, love, and humor, portraying people caught in the drift of political and economic forces well beyond their reach.

After finishing Cheryomushki, my commitment to understanding the world with photography was again substantiated, because with these pictures I was offered a look into such a unique and unlikely corner, witness to something entirely foreign and different, but in them I also saw myself. Like Disfarmer – his remarkable oeuvre unearthed well after his death – or Bellocq’s Storyville Portraits, Nikolay Bakharev is another unexpected discovery, a photographer of humble origins but with incredible insight, revealed in thoughtful, simple, and engaging pictures of a surprising moment in time.

Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

____________

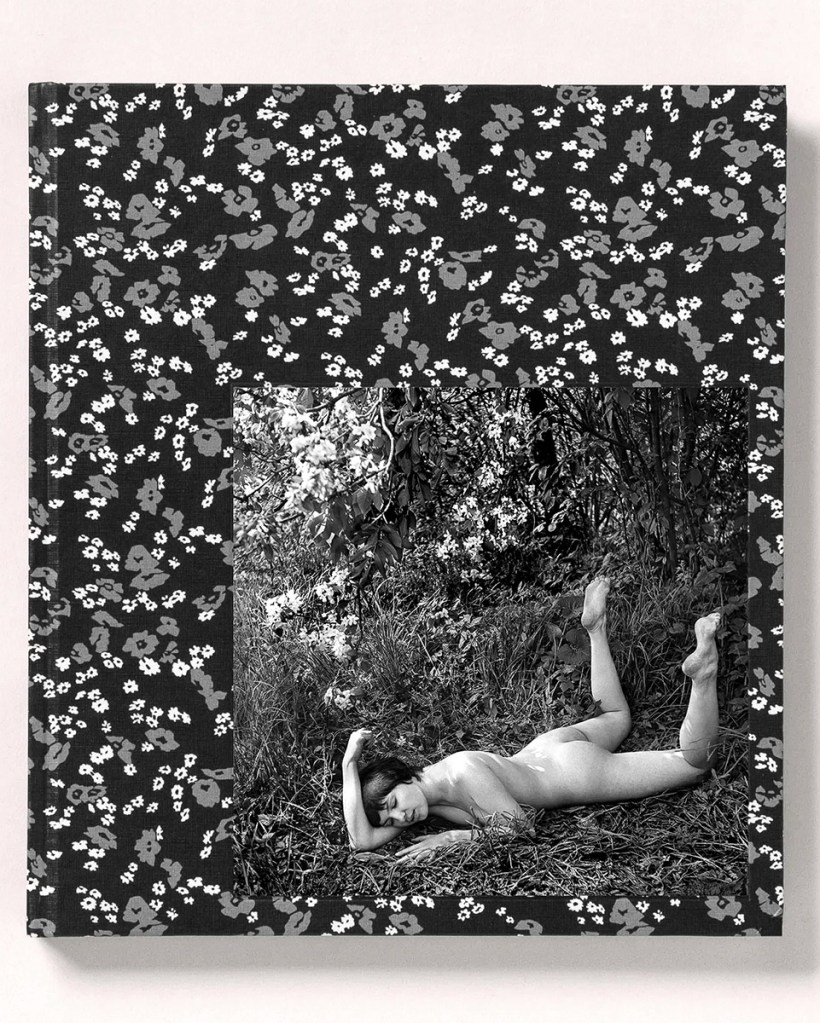

Nikolay Bakharev – Cheryomuski

Photographer: Nikolay Bakharev

Publisher: Stanley/Barker

Text: English

Designer: Sheret

Hard cover with tipped in photo; 240 mm X 270 mm; 120 pages, ___ B / W photographs; ISBN 978-1-913288-82-2

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment