Review by Brian O’Neill ·

Stephen Voss is a photojournalist. You may have seen his work and portraits in Newsweek, Time, The Washington Post Magazine, and more. As a critic and collector of photobooks, I have a few books by photojournalists on my shelves. Perhaps you do too. They often follow a familiar format of, I find, two types. The less conceptually ambitious projects survey a career – portraits abound of dignitaries, famous families, and faraway places. Otherwise, one finds work around a specific issue that has already been deemed as important, of historical significance even, by news media – poaching, smuggling, human trafficking, homelessness, poverty, wars, etc. Some projects ultimately reveal themselves to be more worthwhile than others, which does not take away from the fact that the issue itself was/is deeply important. This is not an assessment on any of the above.

But, Stephen Voss, a photojournalist, has, I think, found a third way. His 2024 release, The Haunting of Verdant Valley, is a fascinating, ambitious, and poignant artifact of 21st century America. To understandThe Haunting of Verdant Valley, you have to begin on the outside, so to speak. Voss, alongside the Pittsburgh based team at Sleeper Studio has considered every dimension of this project and the presentation of the book itself. The carboard packaging is designed with a “101110,” etc., theme, that is, binary code, with the title of the book neatly hidden within it. Then one encounters a package within a package – a Faraday bag. Named after a 19th century English physicist, Faraday bags shield against electromagnetic fields. They are favored within the prepper community, among others, as a way to prevent hackers of various sorts to add, delete, or otherwise penetrate the cyber security of phones, tablets, and computers. While these types of bags can be made of many materials, as far as I am aware the book was shielded with the static dissipative polyethene type.

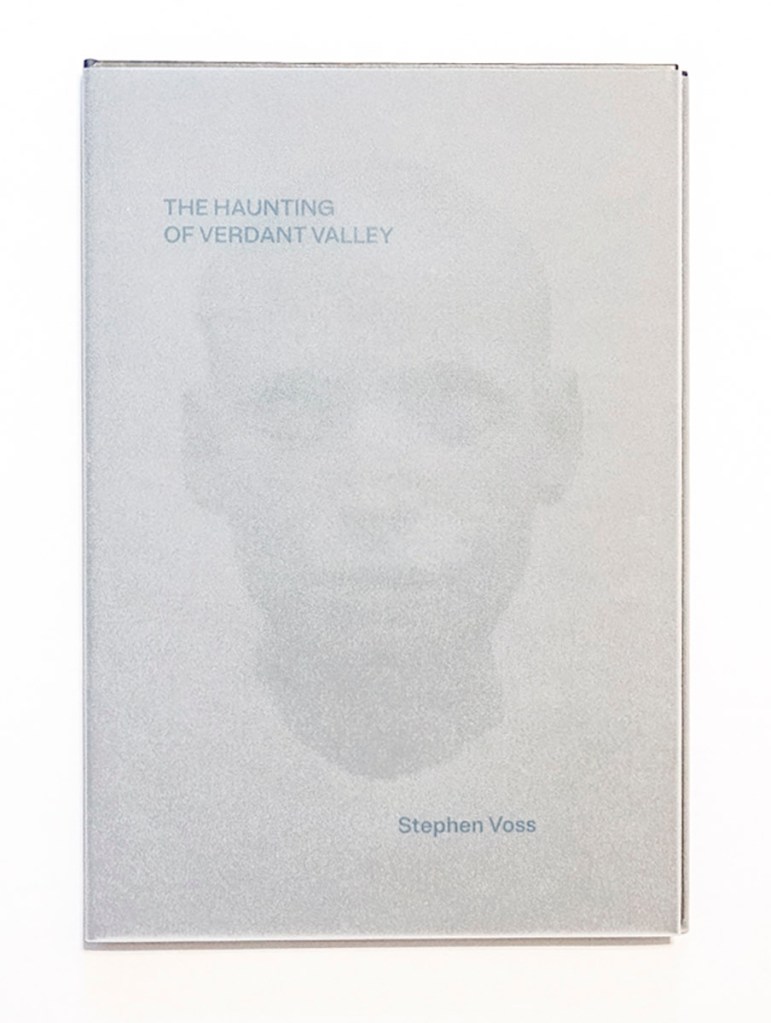

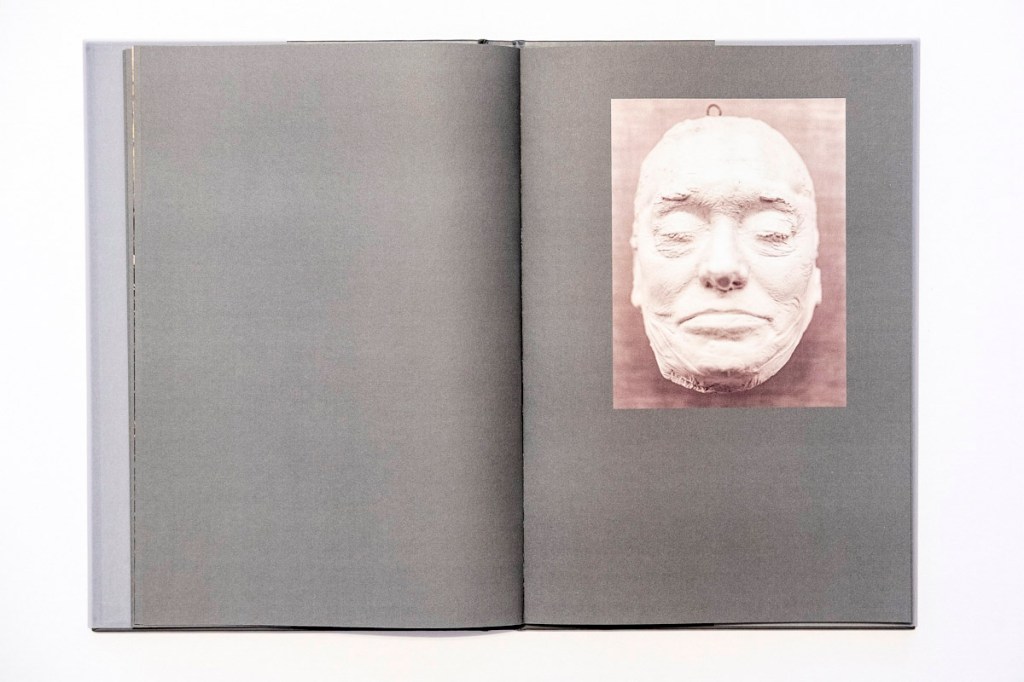

Getting to the book then, made of the most primitive material yet – paper, the cover is a sturdy vellum, acting as a dust jacket, and through it the viewer can see a face with eyes closed, approximating a digital rendering. It seems to be a figure dreaming, shutting one’s eyes (more on these faces below – but the use of one here further expands the interpretive horizon of the project). The face on the cover remains ambiguous and therefore ghostly, haunting. With all these elements taken together, I am at a loss to recall a book so expertly working with “a tone” within the context of the atmosphere of the object itself, and all before one even considers the content of the pages.

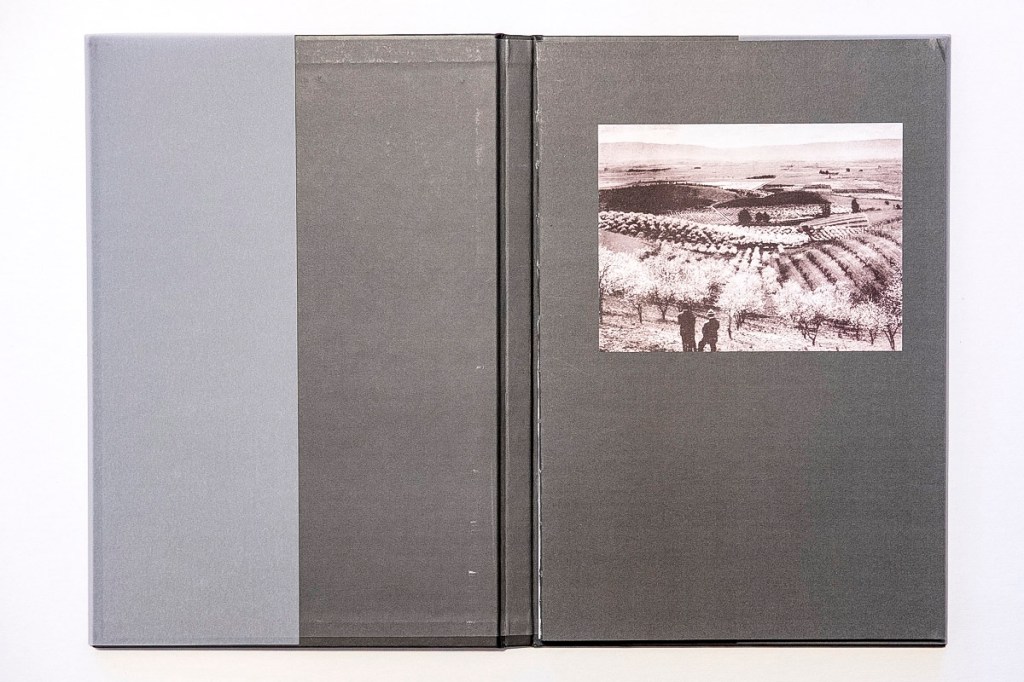

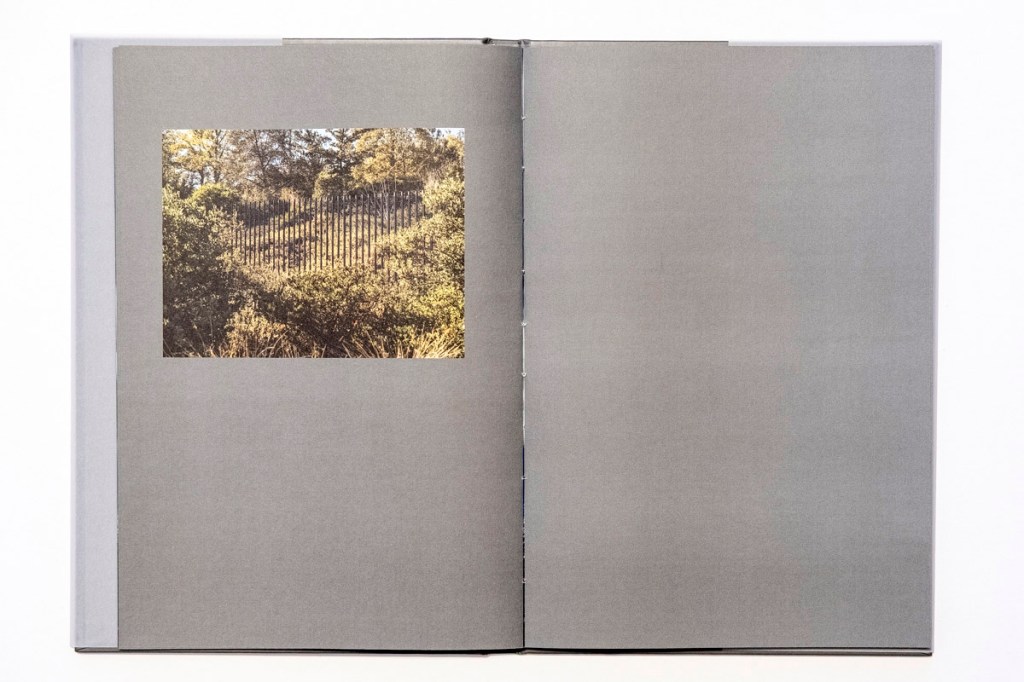

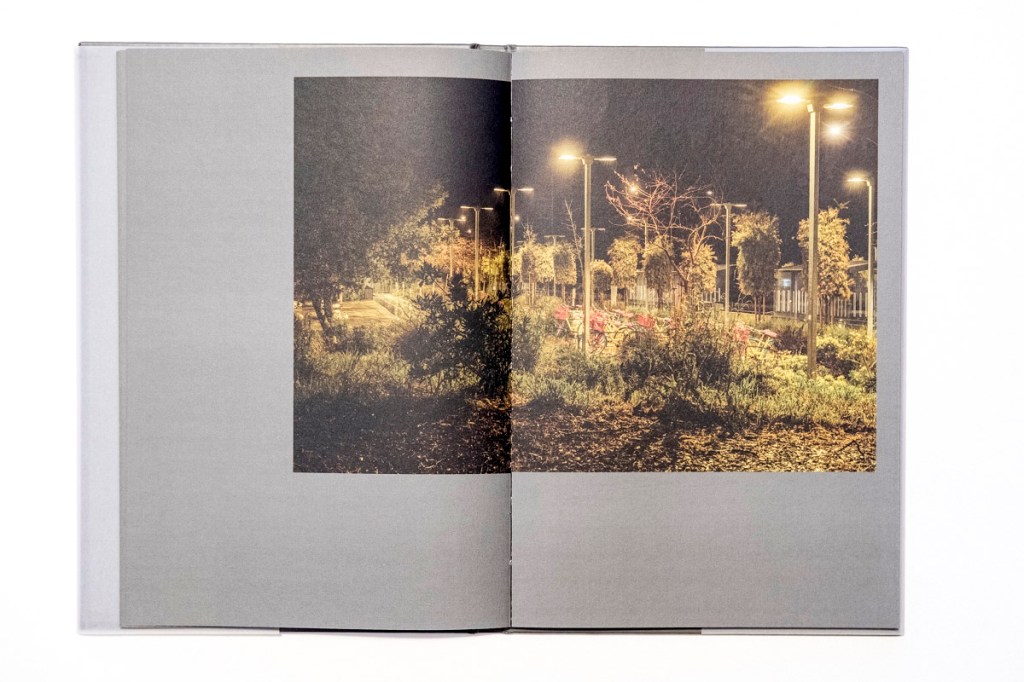

Invited into the book in this unique way, the viewer then encounters 39 images, one of which is an historical image of the Santa Clara Valley, which is described as: “orchards abloom in springtime near San Jose – photographer unknown.” The rest of the images are in color, set against grey pages, sewn together with an exposed binding enveloped in thick cardboard covers. Indeed, it is with the first image – of two men in hats at the bottom of the frame looking out, seemingly surveying, or content, with the verdant valley below – that the viewer begins to understand Voss’ idea even better, this notion of “haunting” that he implies and that becomes clearer throughout the book. This book is about a place that has been and continues to be a palimpsest of, if not “binary,” then dialectical oppositions, of human labor and industrial capacities. Voss hints at this in his text that concludes the book as well. The book’s title comes from Malcolm Harris’ Palo Alto: A History of California Capitalism and the World: “Palo Alto is haunted,” writes Harris.

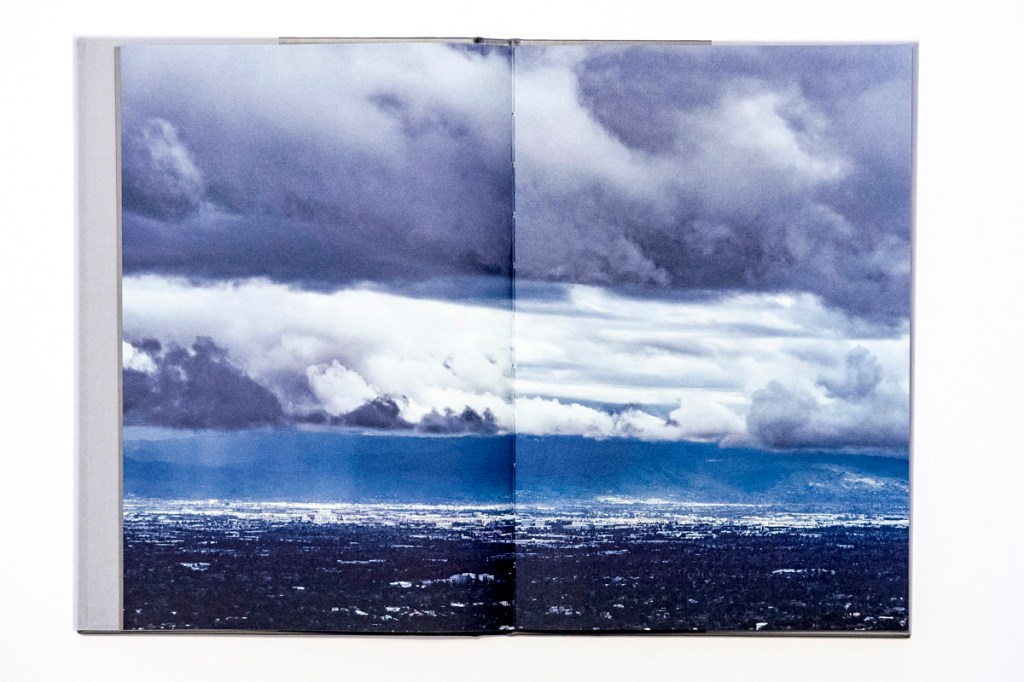

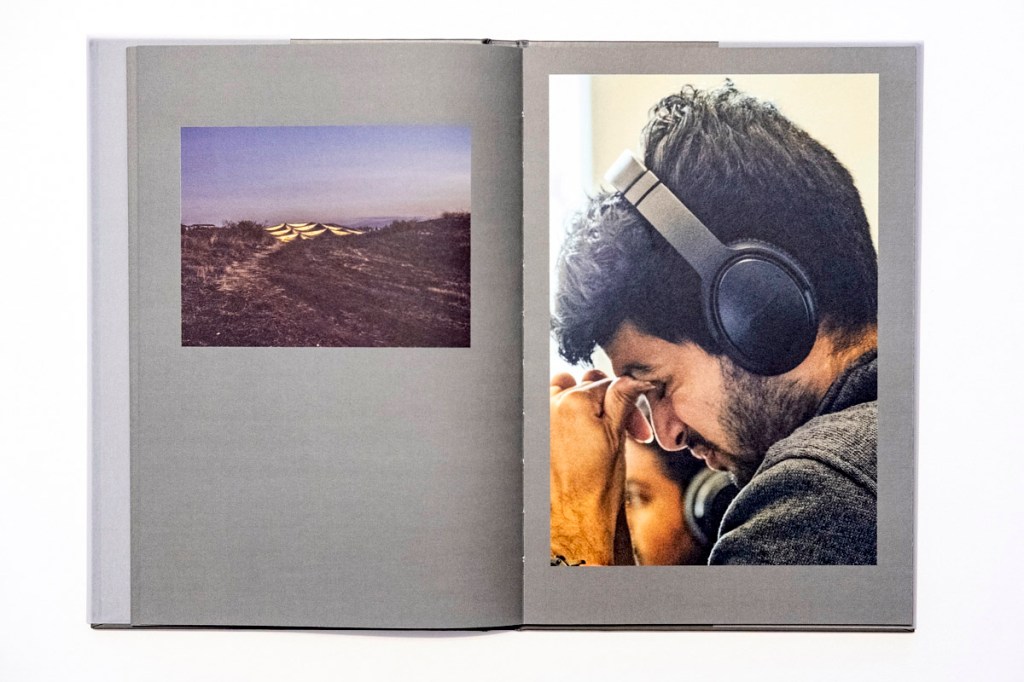

One of the persistent visual themes throughout the project is a concern with blue. Blue light is of course the much-maligned emitted wavelength of computer and phone screens. These have been connected with interference with human circadian rhythms, with some degree of ocular damage, and other effects. One of the early images of the book is a striking vertical portrait of a man, hands in front of face, mouth closed, and (perhaps) pensive – the scene taking on hues of blue magenta, from a screen, a video conference?

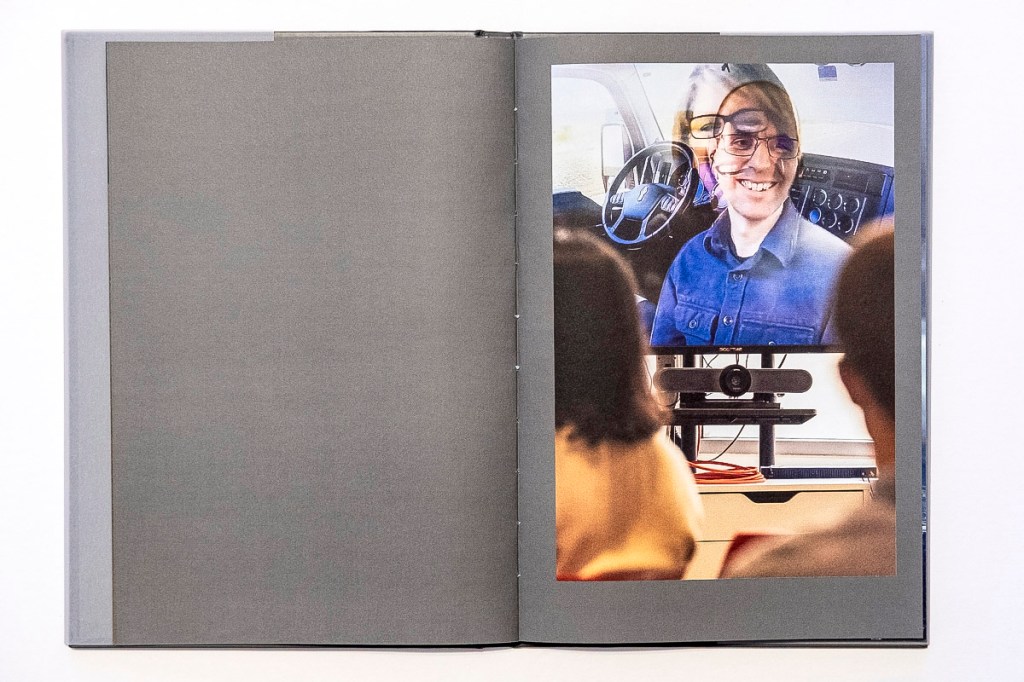

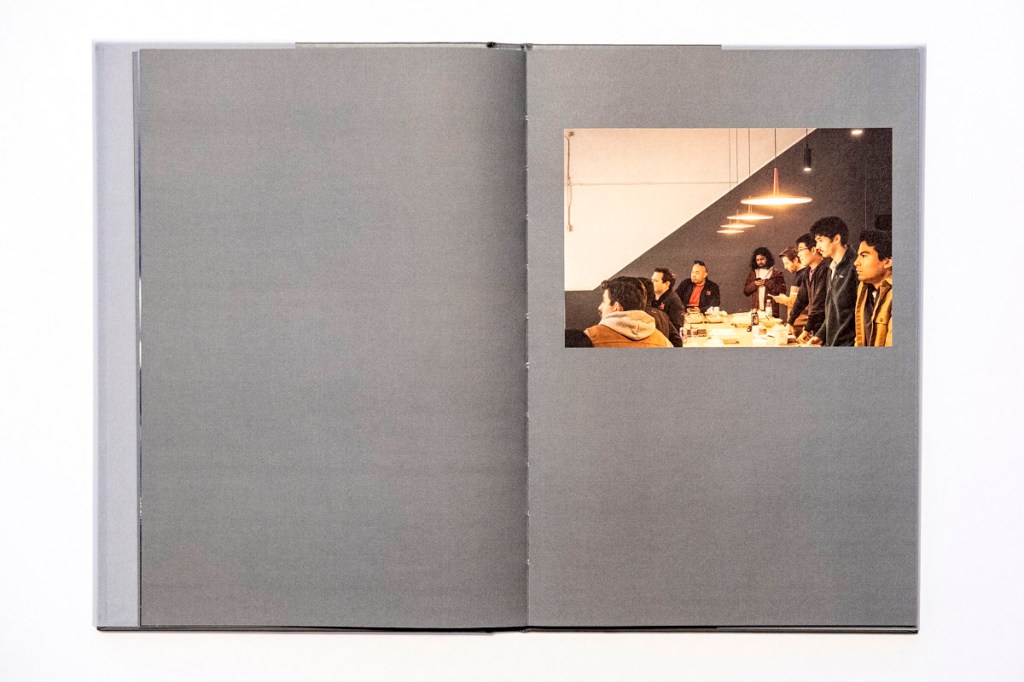

Furthermore, Voss’ choice to focus on the banal and mundane is an important feature of this work. People are often at work, and on their way to work. Work seems to follow everyone everywhere here in a seemingly “normal” place, an unsuspecting place. It is a place of green trees and sun and rain. In this way it is a project about “everyday” – about the phenomenal experience of Silicon Valley. It is not about tech gadget releases and spectacle, but rather, throughout the project Voss points to making the quotidian strange through his use of light and composition, never discriminating on the types of subject matter that can help illustrate this story (barricades and closed gate structures are worked in throughout as well, articulating the atmosphere of surveillance and enclosure – ubiquitous features of bourgeois cultural geography the world over). For example, in one of the more notable “passages,” if I can call it that, of the book, we see a double page spread of a large monitor in an anonymous office building that reads “Tap Controller to Start,” which is followed by an abandoned house. The shiny new surface of things covers over the history of place. Then these ideas coalesce in the following image – a telephoto view (or close crop) of a conference room with onlookers regarding a screen. Simultaneously, a Logitech® camera eye is looking back, and two people, not one, are on the television, caught by Voss’ camera in an overlaid moment: two smiling faces, one over the other. This is but one example of how Voss expertly places the work of performance at the level of everyday existence in Silicon Valley into question time and again. The smiling faces on-screen contrast with that of the more candid portraits of pressure, anxiety, and boredom.

Interspersed in the sequence are also some images of casts of faces. With closed eyes and being largely expressionless they are vertical frames, and they are used judiciously. As Voss reports in his closing written text to the book, these are the “Stanford family death masks, mounted behind glass amidst a large collection of family heirlooms” at the museum on the Stanford University campus. In this same passage, we learn that these death masks provided an insight for Voss about the history of colonialism as connected to the growth and progress of California – Governor Leland Stanford supported militias who were responsible for driving Muwukma Ohlone Tribespeople off their land and exploiting Chinese labor for railroad work. As such, the use of these images, of “death masks,” speaks to the larger themes of the bodily engagement with the place and technology. Interpretively, they are at their most poignant when considered in light of the ephemeral, smiling, highly emotive faces on the screens of the conference rooms Voss has photographed, thus raising questions about permanence on the human and technological level, as well as degrees of performance and stability writ large, issues that are ever-present when thinking about firms like Google et al.

It is the articulation then, of a concern with the digital, symbolic, and material landscape, as well as with the multiple human dimensions at play, that unites the various elements of Voss’ book. As it closes, one turns the book over to find a quotation from E.M. Forester’s dystopic and cautionary short story from 1909: The Machine Stops:

“cannot you see, cannot all you lecturers see, that it is we that are dying, and that down here the only thing that really lives is the Machine? We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralysed our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it. The Machine develops – but not on our lines. The Machine proceeds – but not to our goal?”

As the quotation intimates, Forster’s story problematizes a society that has become over-reliant and overly optimistic in relation to its uses of technology. The problem Forster saw was not in the technology itself, but in its excessive dimensions, those facets that spill out of it in the way that they imply and impact humanity. One of the main problems he saw, and perhaps predicted, was how technological forms could be utilized in ways that would be substitutes for humanism and for critical thinking. Forster depicts a society in which the majority of the population has reached, not enlightenment, but contentment in thinking about, discussing, and (re)producing ideas within the context of a mechanized, and indeed a rational society. Forster’s story is often analyzed as a cautionary tale about artificial intelligence and the internet, but its themes remain generally applicable in its concern for a thoroughly humane society. Like Forester then, Voss troubles the viewer/reader – what is our goal and what is the role of “The Machine” in that?

The idea of haunting, as it runs through The Haunting of Verdant Valley, is further interesting, because hauntings involve agency. Ghosts and phantoms spur protagonists into action. We can take this literary function seriously as it has implications for us – readers, writers, and photographers interested in books and bookmaking. In an era when society needs photojournalists and documentarians more than ever, in a simultaneous moment that democratic principles in regard to, among other things, freedom of the press and critical expression, are threatened in the United States and around the world, Stephen Voss’ work stands as an inspiring path forward: self-directed, self-produced, and uncompromising. The assignment of The Haunting of Verdant Valley was nothing more than a duty designated to himself, by himself, and with a responsibility to society for reporting about his findings resulting from this self-imposed duty. It may in fact be that it is only within this sort of framework that truly fascinating projects, and especially ones about crucial social problems, can manifest today.

Brian O’Neill is a sociologist, writer, and photographer from Phoenix, Arizona.

____________

Steven Voss: The Haunting of Verdant Valley

Photographer: Steven Voss (Born in 1978 in New Jersey, lives in Washington D.C.)

Publisher: Sleeper Studio, Pittsburgh, PA © 2024

Language: English

Printing: Conveyor Studio, Clifton New Jersey

7.75” x 11.5”, 72 pages on uncoated paper, 39 photographs, Vellum paper slipcover, Swiss Binding, Hand-numbered edition of 150

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment