Review by Matt Schneider ·

If you have a car accident and you’re seriously injured – your left leg is broken, your right arm, nose broken, head broken, who knows what – then they put you in intensive care and everyone can see that you’re in a real mess.

But if one day you break your foot, then you break your arm two years later, and you break your nose after another three years, nobody talks about it. Because – that’s normal. They only talk about it when there’s a bang. And this bang, this huge car accident, has never happened here, because the open-cast mine is moving. It doesn’t stay in one place.

It’s unstoppable, but it’s not like saying, whoa, we have to leave here tomorrow. There are people who accept it, who say that’s just the way it is. Some can. I can’t – I never could. That’s my problem.

Wilhelm Hoffman, former resident of Etzweiler (p. 11)

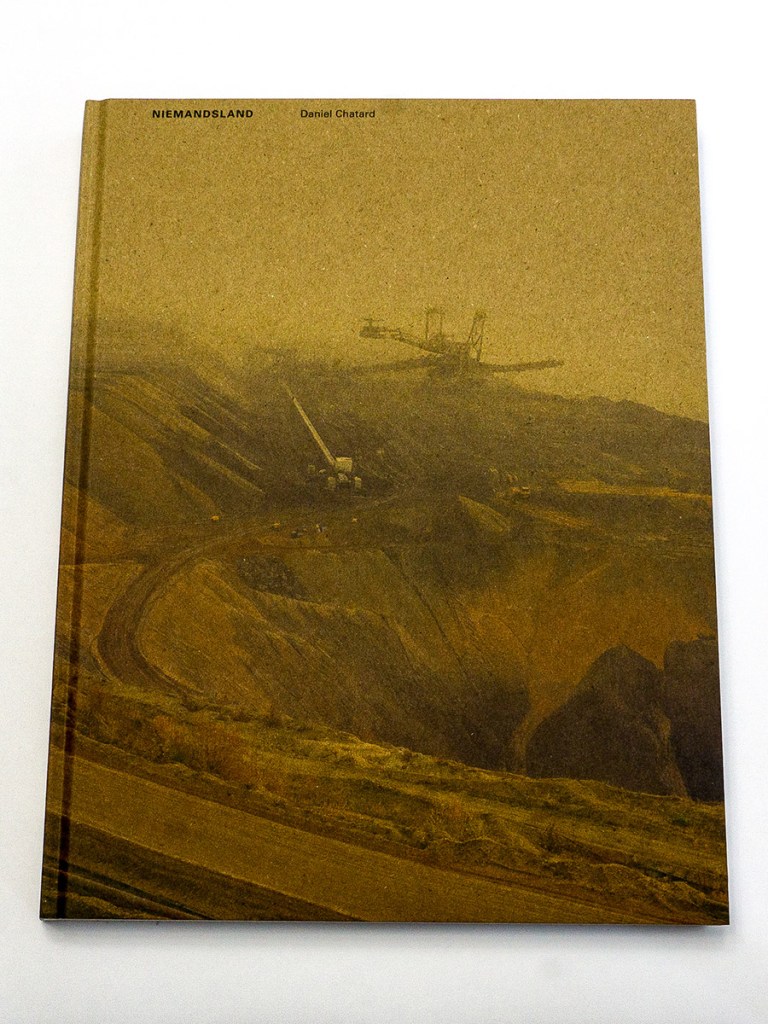

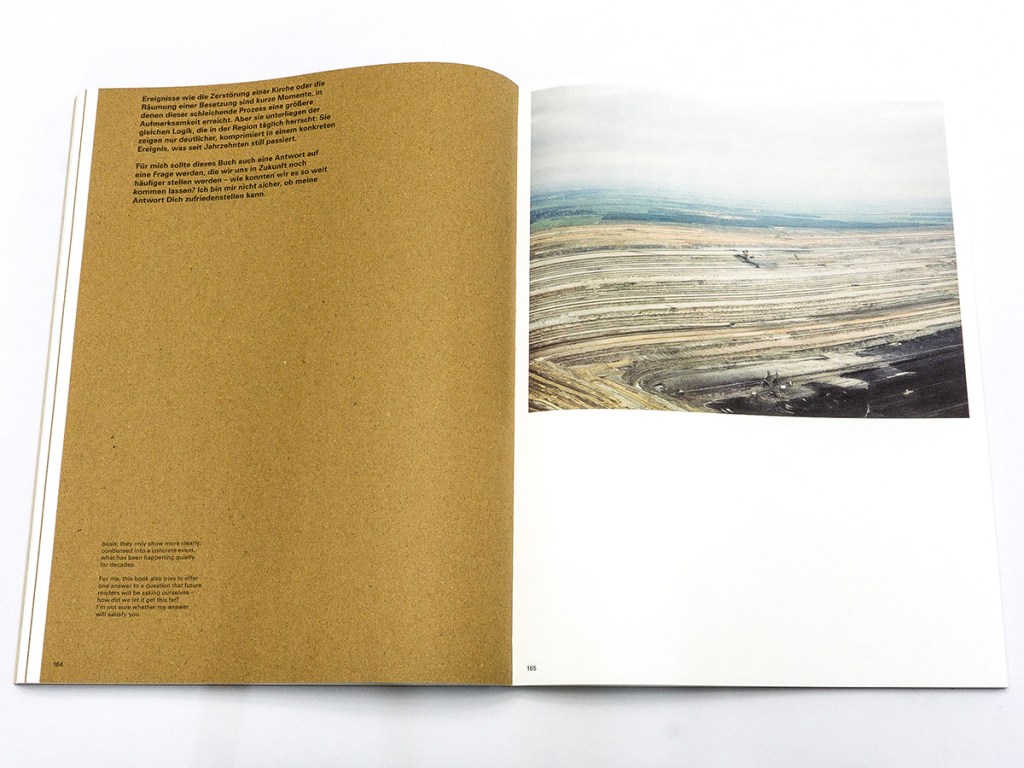

Niemandsland by photographer Daniel Chatard is a wonderful addition to Eriskay Connection’s thoughtful lineup of photobooks on the politics of climate change, which includes other notable titles like Forgotten Seas by Tanja Engelberts and Bron by Zindzi Zwietering. With 224 matte pages measuring 240 x 320 mm, it’s an imposing and visually interesting work to engage with and study. Chatard is clearly a skilled photographer, but it is worth noting that this photobook is as much a work of history and political commentary as it is a work of photography. Truthfully, writing a review for Niemandsland has been a difficult task, not because I did not enjoy the photobook or because I thought it was of poor quality, but because I am afraid that I cannot write a review that does this excellent book justice.

By documenting the industrial mining activity of German energy giant REW, Niemandsland – meaning “no man’s land” in English – interrogates the relationship between community, physical space, and environment in the Rhineland. Through the use of photography, transcribed notes, archival materials, and bits of personal correspondence, Chatard provides important commentary on climate change, politics, resistance, capitalist extraction, and personal and communal loss. While this is most directly a story of the German Rhineland, this work should carry significance to readers around the world.

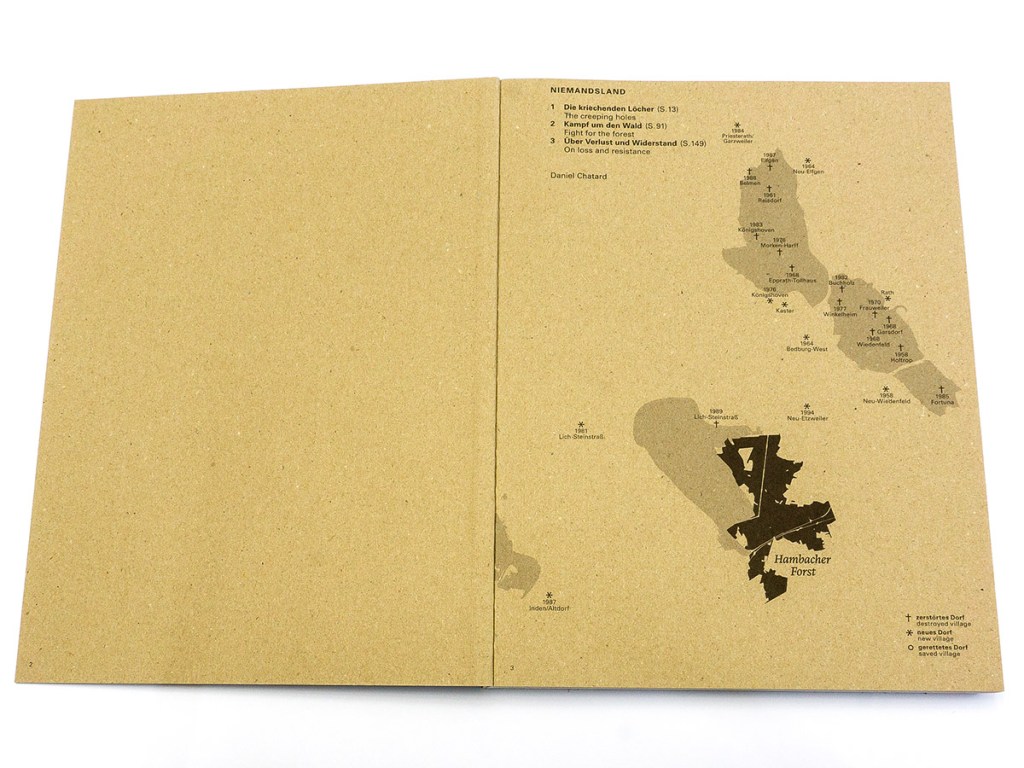

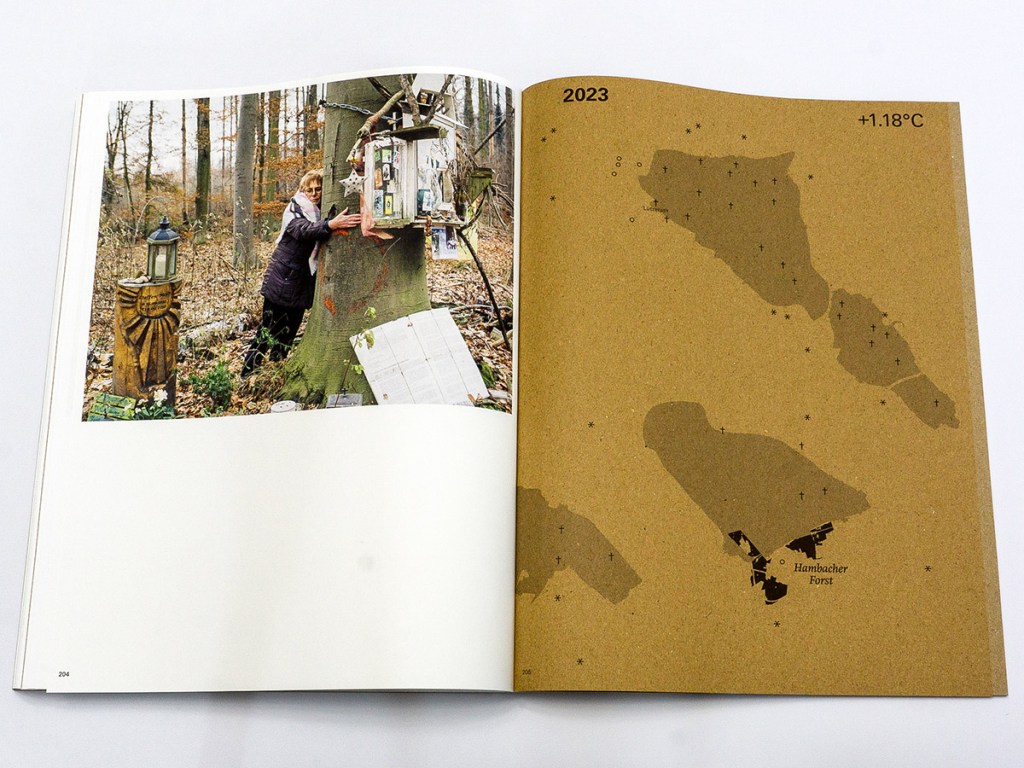

The book’s most significant feature is a series of maps, each dated between 1997 and 2023. The first map appears as the background to the table of contents, and as I tried to make sense of it, a shiver went down my spine. I realized that I was looking at a map of villages destroyed, villagers displaced, and villages spared by RWE’s ever expanding open-pit coal mines. Signified by a dark black tract, each map shows Hambacher Forest, and from page 1, I found myself worried about the threat RWE poses to it. When I reached the second map on page 15, I was further unnerved to find the 1997 map’s upper right corner marked with “+0.49°C,” representing the rise of the average global temperature driven by fossil fuel extraction and consumption. As I moved through the book, my anxiety grew with each passing map. Each map promised the passing of a year, a warmer planet, and a smaller forest. The map for 2016 was the most devastating. As I turned to page 85, I immediately noticed that Hambacher Forest had been broken into two separate areas, and my stomach dropped.

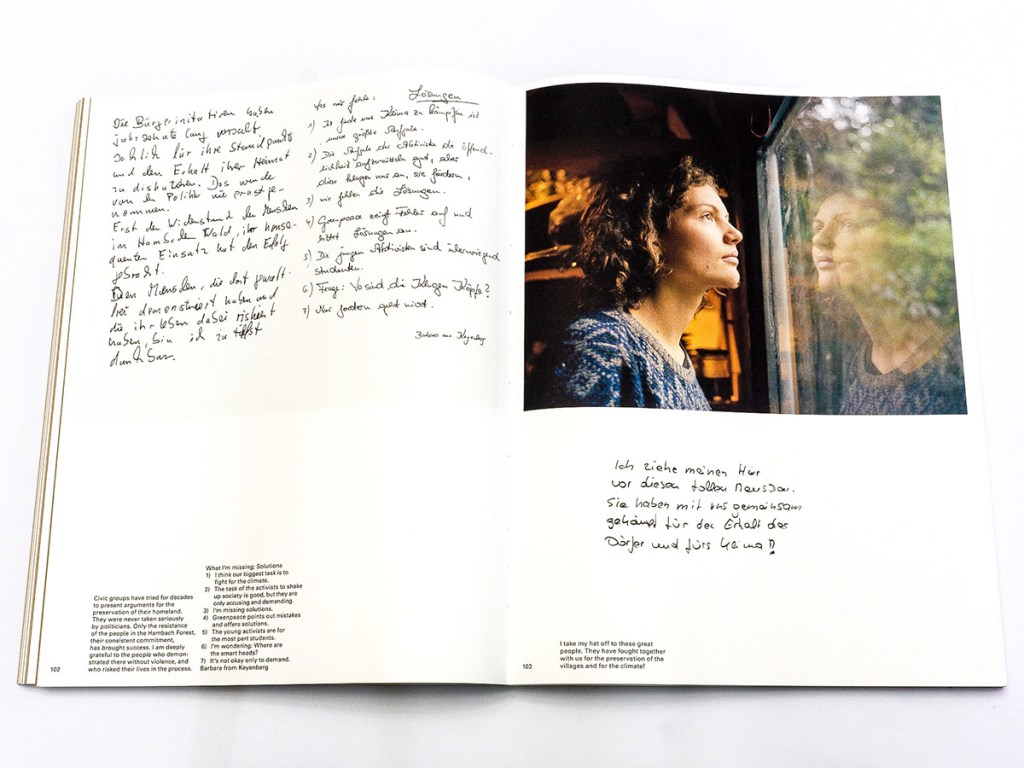

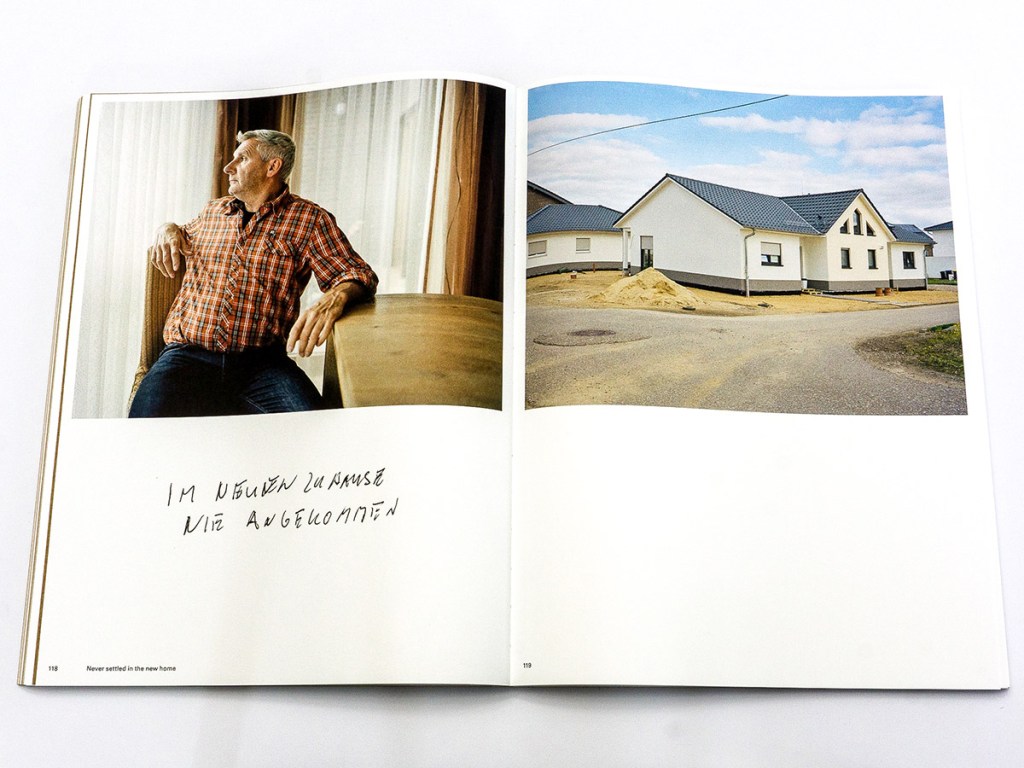

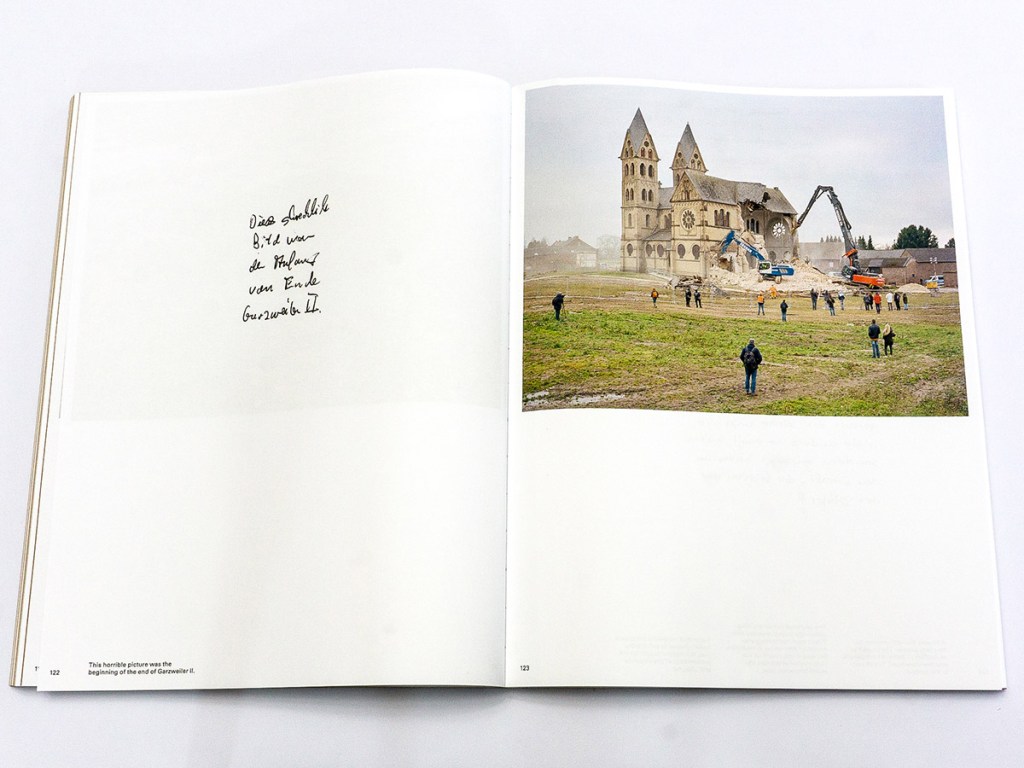

Parallel to the story of climate change and environmental degradation are stories of the communities impacted by RWE. The book is littered with news excerpts about notable happenings, stories of resistance, and images that made me feel like I actually know (or knew) these German communities. Chatard, to be sure, makes it a point to highlight the communities’ victories in their battle against RWE’s insatiable appetite for destruction. And yet, it is hard to describe the overall arc as one of anything other than loss. To mine more coal, the pits needed to grow. The growing pits meant towns needed to be relocated. The sense of loss and betrayal was, perhaps, best symbolized by a photograph of villagers gathered to watch the razing of their community church in Garzweiler II (p. 123), but it was a short field note from Chatard that has most haunted me since my first reading of this book: “A farmer from Keyenberg had a vegetable garden there. After handing over his keys to the buyers at RWE, he came to see me on the farm in Lützerath and gave me a bottle of brandy as a farewell gift. A week later he died in Erkelenz. He had spent almost his entire life in Keyenberg” (p. 176).

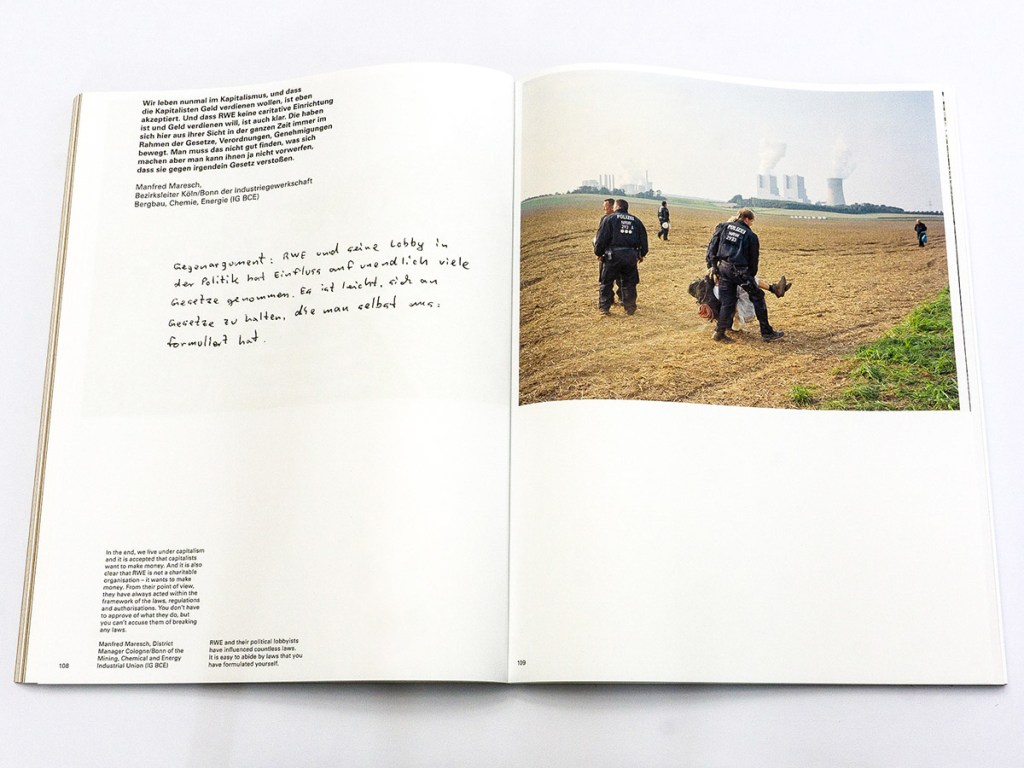

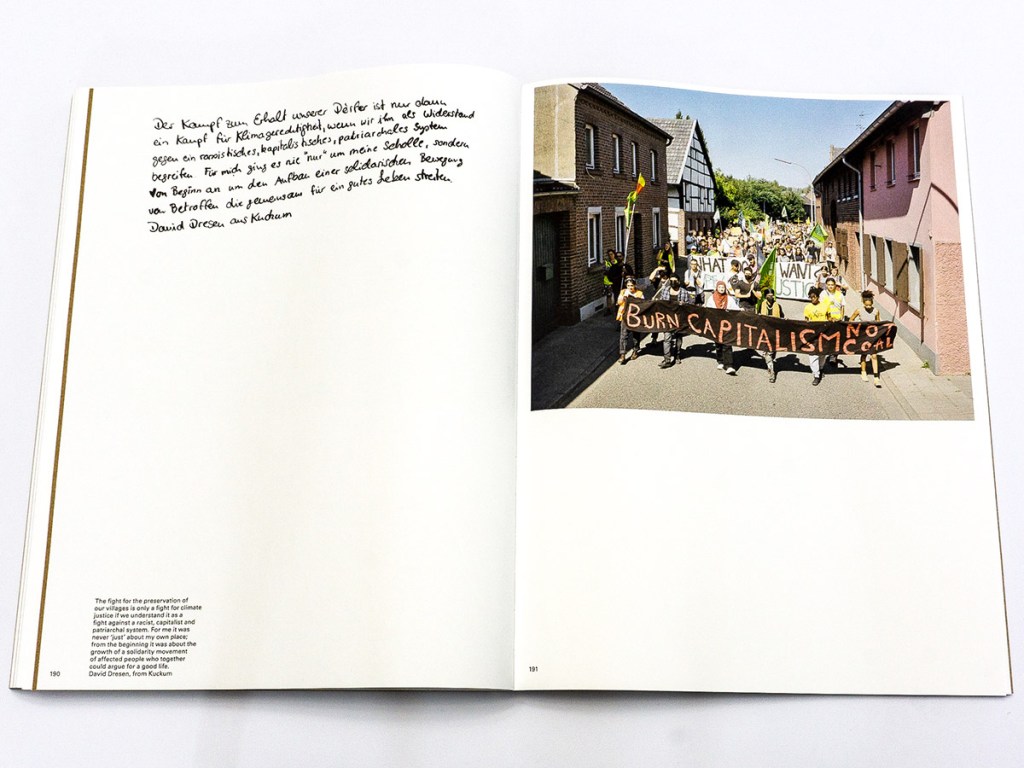

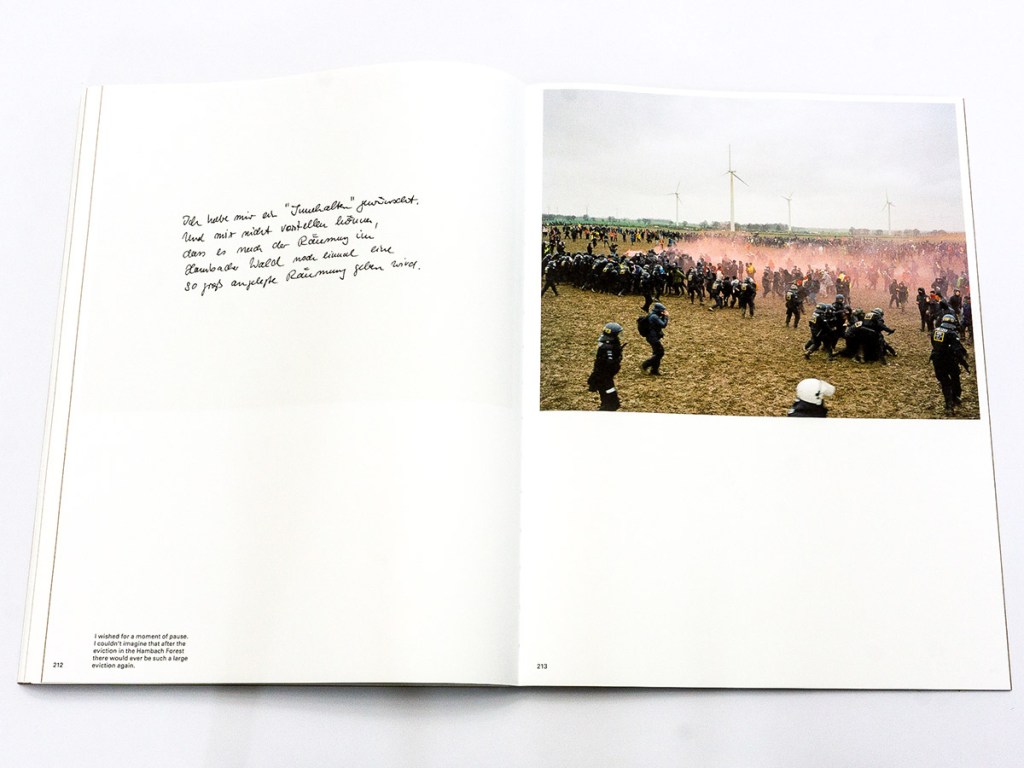

Despite this sense of immense loss, Chatard is right to conclude his book by capturing a sense of righteous anger, stubbornness, and even hope in the face of industrial and state violence. In one photo, he captures an army of police dispatching a crowd of protesters (with tear gas?), the scene set against a field of wind turbines (p. 212). In another, he highlights the root of the problem by capturing a march of protesters proudly carrying a black banner with red lettering that reads “BURN CAPITALISM NOT COAL” (p. 191). Although his field notes make it clear that divisions within these communities remain, it is also clear that life in these communities persists against a backdrop of evictions and the arrest of resisters.

Niemandsland has my highest praise, and again, I doubt this review has done it justice. I hope you will secure a copy and evaluate it for yourself.

____________

Matt Schneider is a professor and visual sociologist in Wilmington, North Carolina.

____________

Niemandsland, Daniel Chatard

Photographer/author: Daniel Chatard

Publisher: The Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands, copyright 2024

Language: English & German

Design and Cartography: Carel Fransen

Photo editing: Daniel Chatard and Aliona Kardash

Text editing: Manuel Stark

Translations: Will Boase

Lithography: Marc Gijzen

ISBN: 9789493363076, Softcover, 24 X 32 cm, 224 pages

____________

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment