Review by Melanie Chapman •

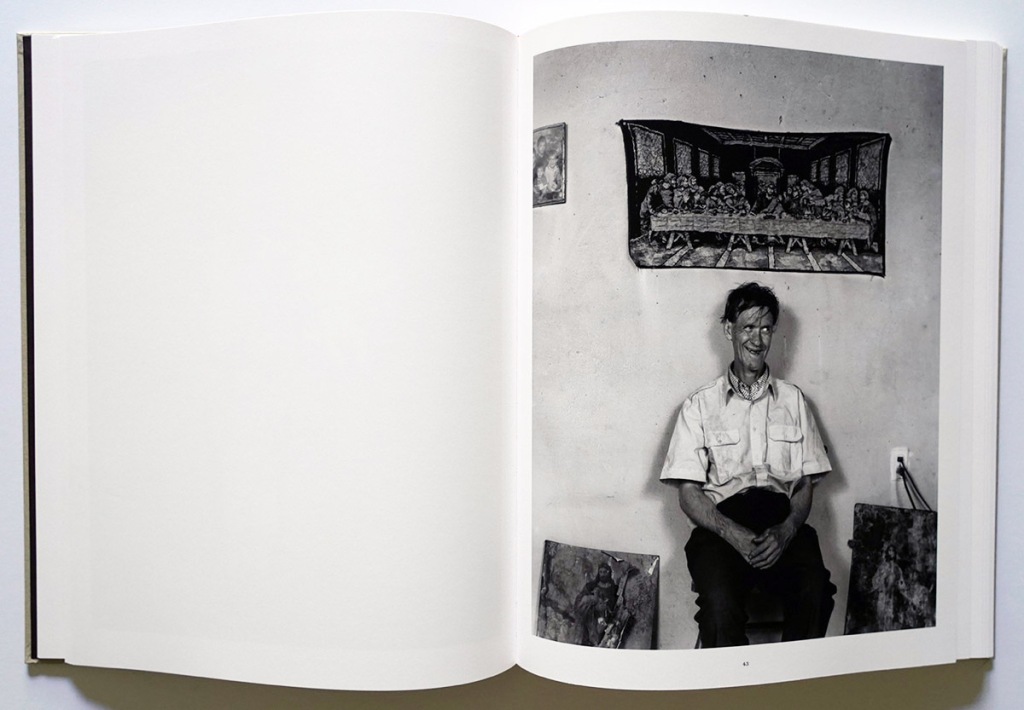

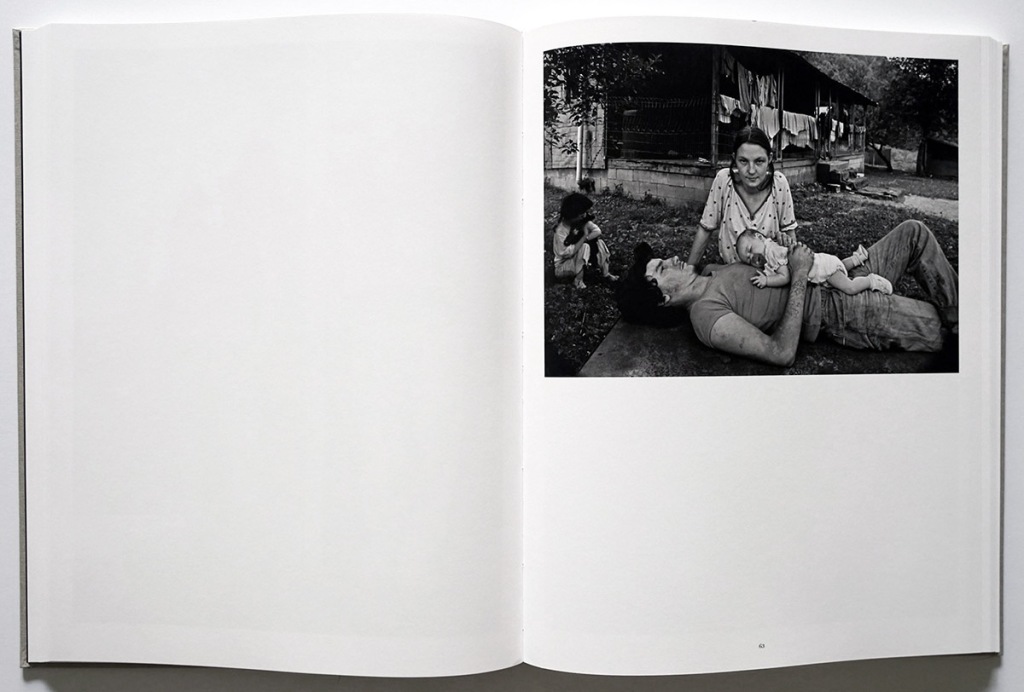

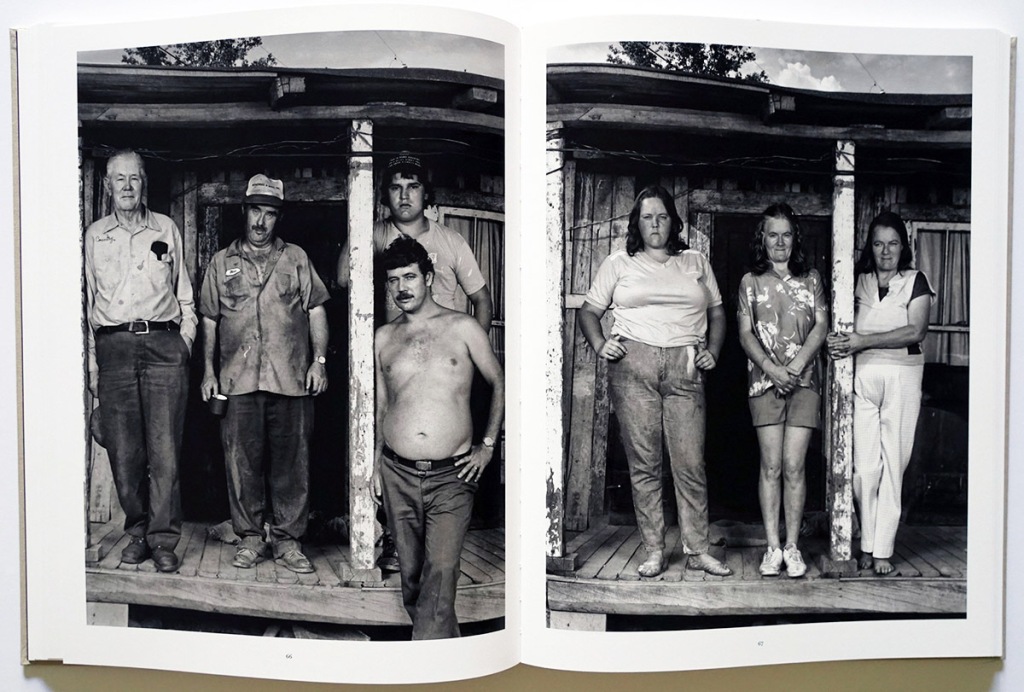

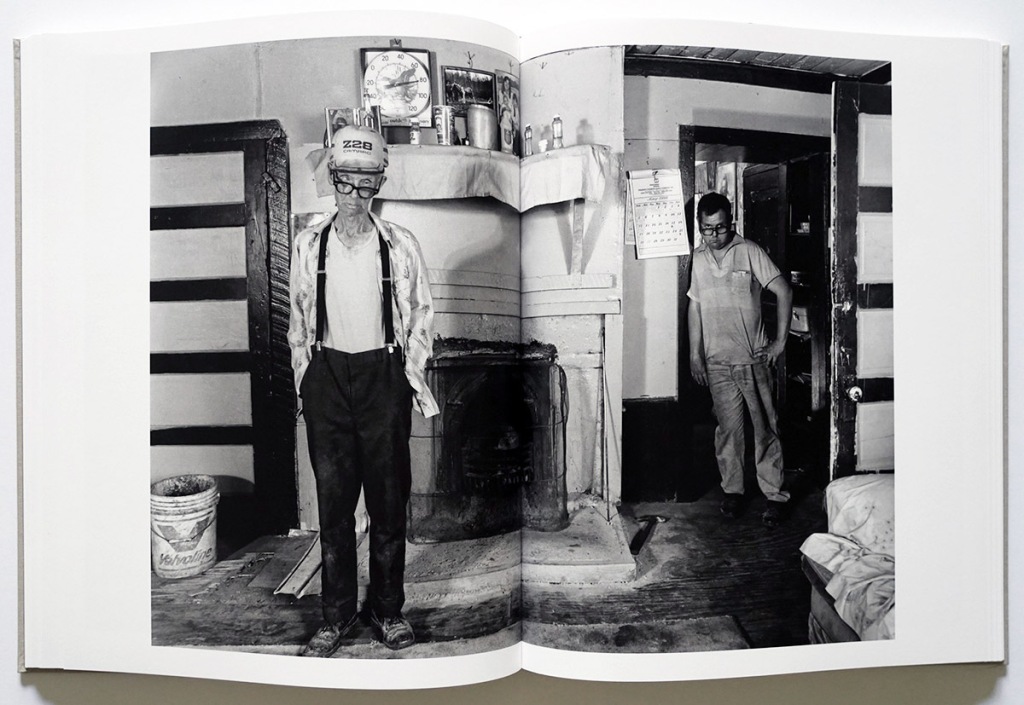

“Never did bother Nobody”: The grounded and authentic culture of rural Kentucky as seen by a native son, From the Heads of the Hollers is a gorgeous new GOST publication of portraits by Kentucky native Shelby Lee Adams. Representing previously unpublished work made over 36 years, Adams’ environmental portraits were created in collaboration with individuals and families raised nestled in the Appalachia mountains of Eastern Kentucky, and offer sympathetic and respectful glimpses of not only hard-working folks for whom life has not been easy, but also the multi-generational bonds that make their lives meaningful.

Fitting comfortably somewhere between the WPA work of Dorothea Lange and the Social Graces portraiture of Larry Fink, Adams’ work is strong on its artistic as well as social commentary merits. Much has been said and written in the past regarding the authenticity of Adams’ images and whether or not his focus on poor white ‘hillbillies’ serves or harms their community. If that is of interest, I suggest you watch the 2011 documentary “The True Meaning of Pictures” directed by Jennifer Baichwal, which offers multiple points of view, including those of critics, subjects of the work, and from Shelby Lee Adams himself. Having watched the film to become more educated about the region in which Adams grew up and his relationship to his subject matter, this reviewer gained a greater respect for not only his technical working process but also for Adams’ investment in the community he photographed.

Unlike the portraits by Richard Avedon, in which his subjects are isolated against a stark white backdrop, Adams appropriately includes the details of the surroundings, be they porches, storefronts, barns, or in-home funerals, as if to say “the landscape is a significant player in these unfolding stories.” Though one senses the subjects were conscious of being photographed (and how could they not, since Adams primarily used 4×5 and 8×10 Deardorff view cameras and strobe umbrellas), they all exhibit an ease in front of his lens, indicating they wanted to be seen, and appreciated his appreciation. The individuals and families that Adams collaborated with for nearly 40 years recognize his sincere interest in them as people (rather than stereotypes), and they willingly participate in his long-term investment to record their lives while making art in the process. Their trust in Adams’ non-judgmental and creative intentions, and the agency he grants them to shape their own narrative resonates throughout this meaningful body of work.

Critics of Adams’ work seem to be more uncomfortable with his images than the truths that they reveal: namely that generations of rural folks were once able to live on and off of the land of their ancestors, and now after decades of coal and strip mining as well as the deforestation from the lumber industry, the well water is no longer drinkable and there are few jobs left to support their way of life. Seems like lots of city folk don’t want to see and therefore acknowledge the depths of poverty that these rural lives experience, nor the exploitation of the poor in the name of capitalism and perpetual growth. Not everyone can be highly educated or upwardly mobile, nor will all little girls be presented as beautiful dolls or become influencer superstars. Many didn’t and won’t have access to high-tech devices that promise access to a shinier future.

Yet that is not to imply that theirs are lives without joy or dignity. As seen through Adams’ lens, these people are proud of their accomplishments, they are proud of their homes and the families who populate them. They worship, celebrate, and suffer, just like human beings do all over the world. They have children, lose parents, time shows its ravages through the lines on their faces, they laugh, they love, they go to sleep when they are exhausted and if the good Lord is willing, they get up in the morning and do it all over again.

Without Shelby Lee Adams, I doubt we would ever have the contemporary and compelling work of Mark Laita, whose ongoing personal film and stills project “Soft White Underbelly” also focuses on the lives of folks often unseen and overlooked. Both photographers clearly know “good subjects” when they encounter them. But neither treat the folks they document as anything less than fully human, unlike (in my opinion) the more celebrated and perhaps therefore more marketable ‘freaks’ images of Diane Arbus. What elevates Adams’ work beyond the strict parameters of photojournalism is not only his choice of equipment and evident mastery of craft, but also his talent as an artist to recognize symbolic moments as they are unfolding or envisioned, and his capacity to stand with empathy among the tired, the poor, the huddled masses, and find in these mountain people the holiness of saints.

For those of us who appreciate social commentary compellingly presented, the finely printed and well-seen portraits of From the Heads of the Hollers will compel one to agree with Shelby Lee Adams himself when he said his intention is “to push and challenge the viewer … to stop making judgments and experience life.” These are “subjectively engaging and involved” portraits of lives that “are not easy, not hard” as Corrine Zabala reflects in the documentary film. Unlike the critic who said of Adams’ photographs “they take me into a territory that I don’t particularly want to go” (A.D. Coleman), Shelby Lee Adams grew up in that territory and has demonstrated a profound appreciation for the land and its people, and we as viewers are the better for it.

____________

Melanie Chapman is a PBJ Contributing Editor and a Southern California photographer.

____________

Shelby Lee Adams – From the Heads of the Hollers

Photographer: Shelby Lee Adams (born in Hazard, Kentucky, USA)

Texts: Shelby Lee Adams

Language: English

Publisher: GOST Books, London, © 2023

Hardcover, stitched binding, 174 pages; printed in Italy by EBS; ISBN 978-910401-79-8

Edited and designed by GOST: Rossella Castello, Katie Clifford, Gemma Gerhard, Justine Hucker, Allon Kaye, Eleanor Macnair, Claudia Paladini, Ana Rocha

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s) and publishers. All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and/or publishers.

Leave a comment