Review by Matt Schneider ·

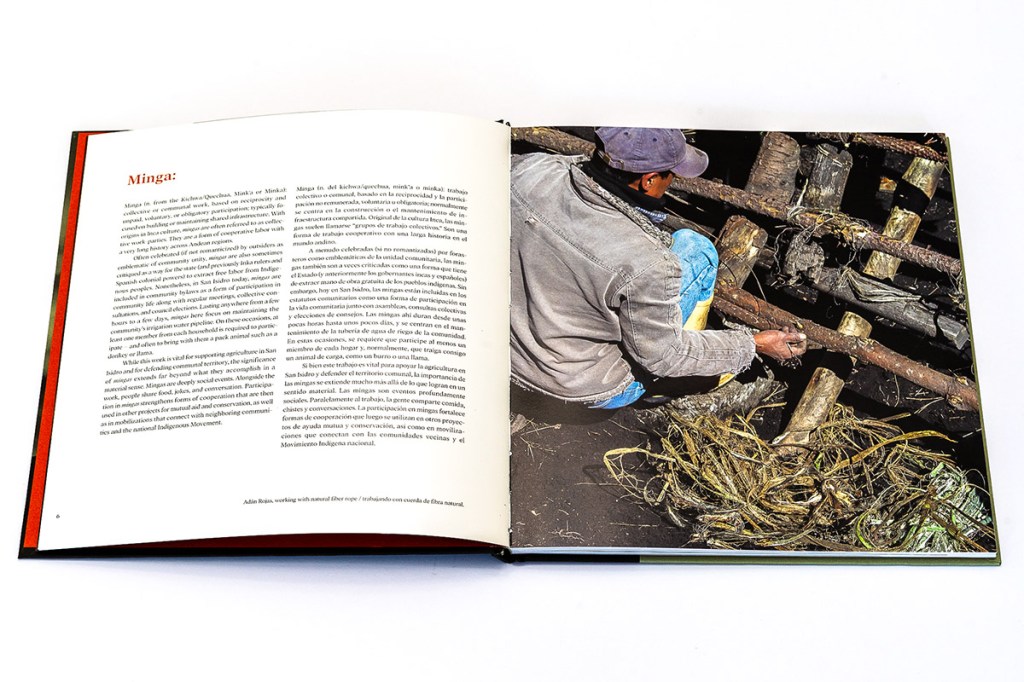

In Mingas+Solidarity, photographer and anthropologist Tristan Partridge introduces us to the cultural tradition of minga in the ancestral community of San Isidro, Cotopaxi, Ecuador. The word “minga” is adapted from the Kichwa/Quechua word Mink’a or Minka, and as we learn from the book’s introduction, indicates “collective or communal work, based on reciprocity and unpaid, voluntary, or obligatory participation; typically focused on building or maintaining shared infrastructure. With origins in Inca culture, mingas are often referred to as collective work parties. They are a form of cooperative labor with a very long history across Andean regions” (p. 6). And it is in a similar spirit of community, collaboration, and shared knowledge production that this photobook seems to have been created. While it is Partridge’s name on the front cover, to communicate the cultural meaning and importance of mingas, the book heavily relies on short written statements from locals who have participated in mingas over the course of their lives, including community residents Porfirio Allauca and Myriam Allauca. With all text appearing in both English and Spanish, it is clear that this book is for a local audience as much as any other.

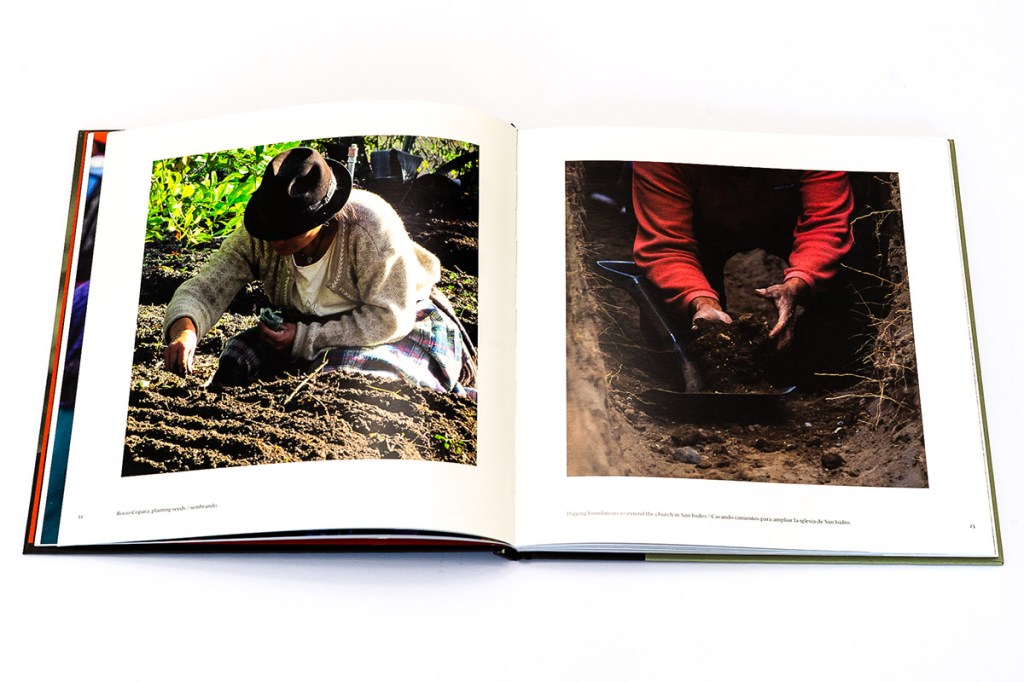

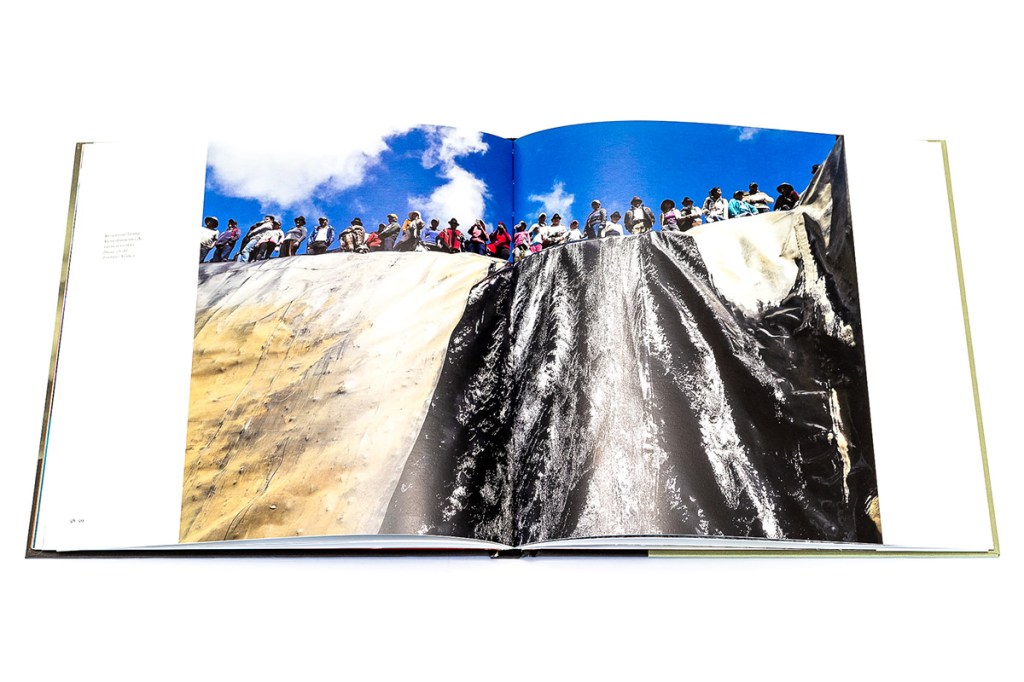

The book is a strong work of documentary photography. Partridge’s photographs provide the reader with a strong sense of community, place, and citizenship. More than this, though, the photos help us understand how community, place, and citizenship are constructed and maintained in San Isidro. As I engaged with this book, almost immediately I noticed that the photographs very frequently depict community members with their faces hidden by hats, shadow, or the angle of the camera. In contrast, and true to the idea of the minga, the work of many helping hands is prominently featured. In this setting, collective effort outshines the work of any one individual. In turn, all benefit from mingas that build social capital, community identity, and even the physical infrastructure – from irrigation systems to churches – required for community life.

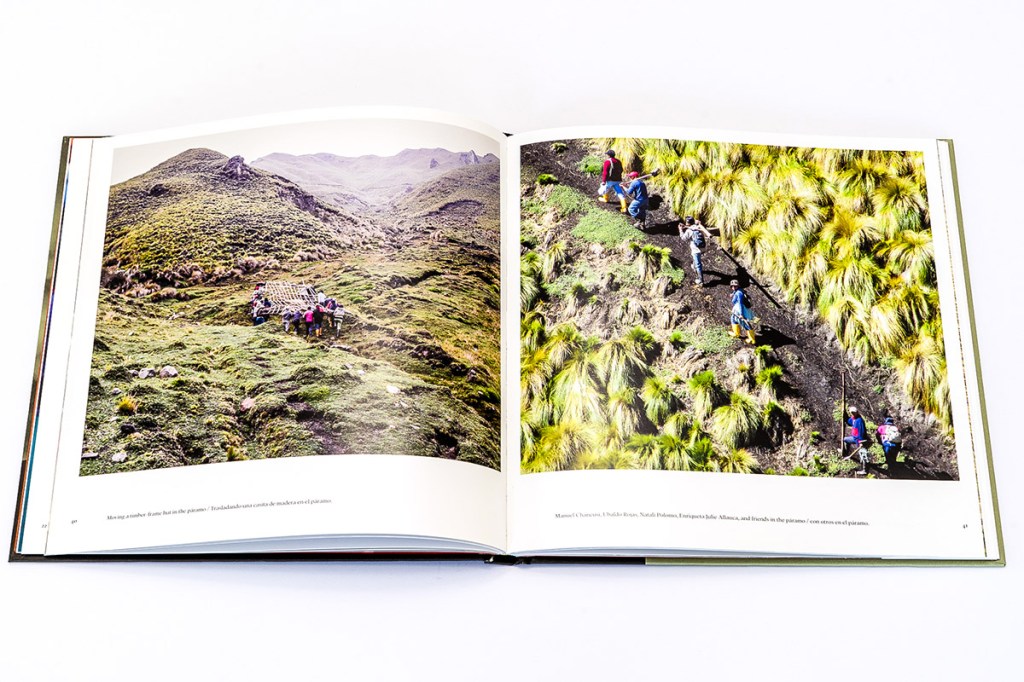

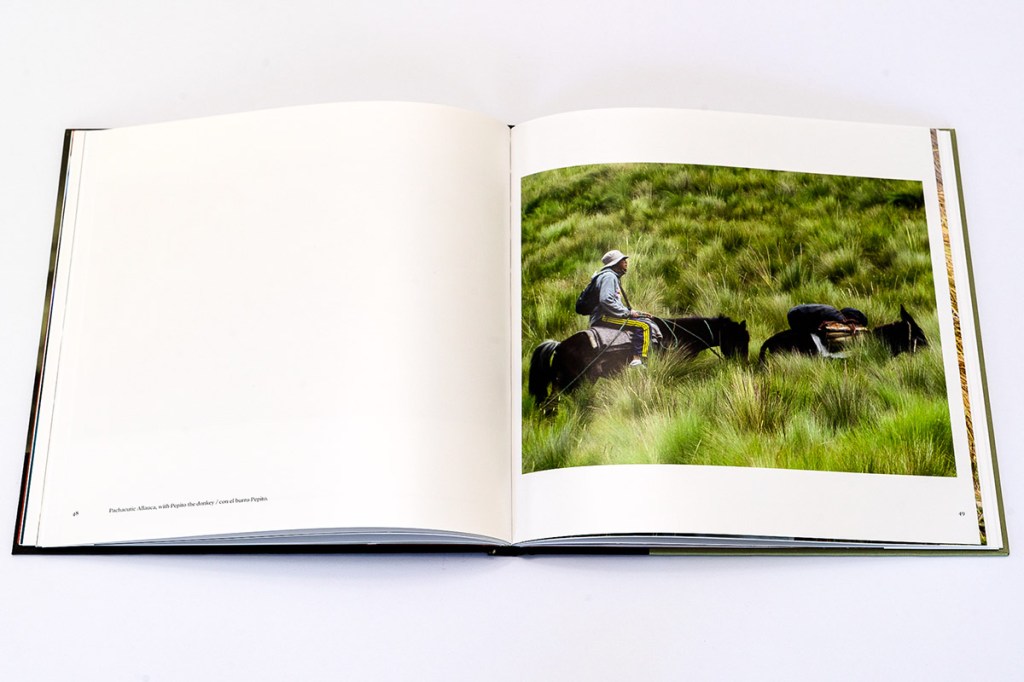

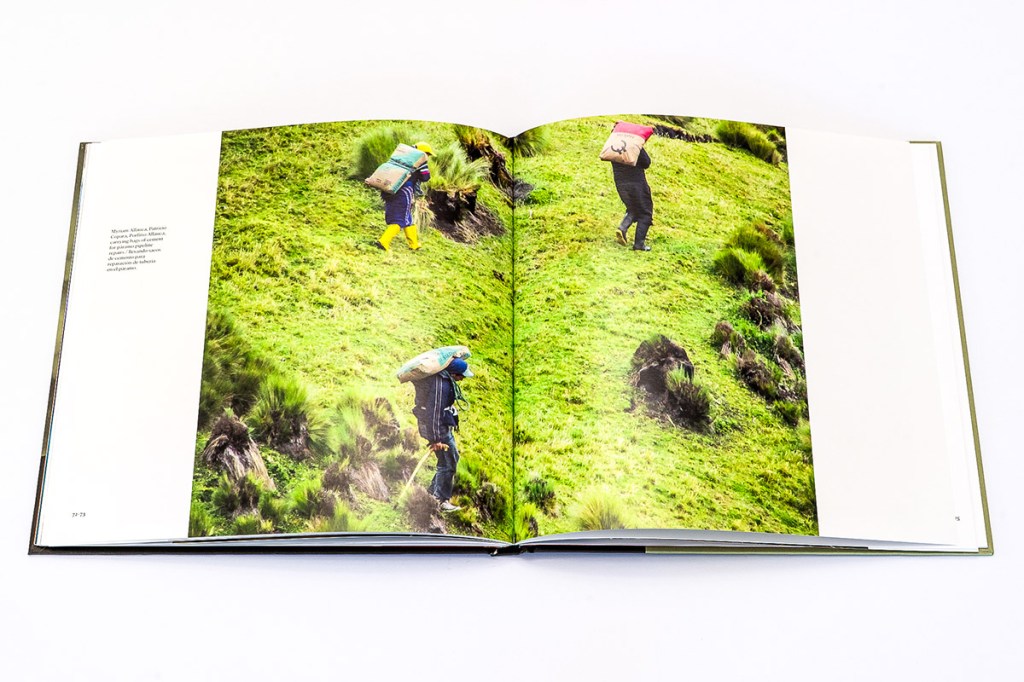

Although I have never been to San Isidro and it has been more than a decade since I spent time in Cuenca, Partridge does a wonderful job of transporting me to the place by incorporating sweeping views of the community (p.18-19) and the distinctive alpine tundra found high in the Andes mountains (p. 40-41). Likewise, Partridge is intentional in his incorporation of cultural artifacts and practices that might be otherwise taken for granted, including prominently featuring the flat brimmed hats characteristic of the Ecuadorian highlands and the preparation of cuy (guinea pig). Perhaps most interesting is the way in which Partridge incorporates the Catholic character of the community into his photos. He does this in a number of obvious ways. For example, he includes photos of the community church undergoing expansion, as well as a dramatic photo of a child looking to a priest in awe just before her baptism. However, through Partridge’s photographs, the labor of the minga also takes on a religious character. Voluntary labor in the name of community building is presented as Christ-like. For example, at various points throughout the book, community members are seen bearing the weight of construction materials, with the photographs captured in a way that resembles the carrying of a cross (pp. 44-45, 51, 75). In other scenes, we see San Isidro residents traveling through the Páramo, sometimes even accompanied by donkeys (pp. 18-19, 49), suggesting the minga is akin to pilgrimage.

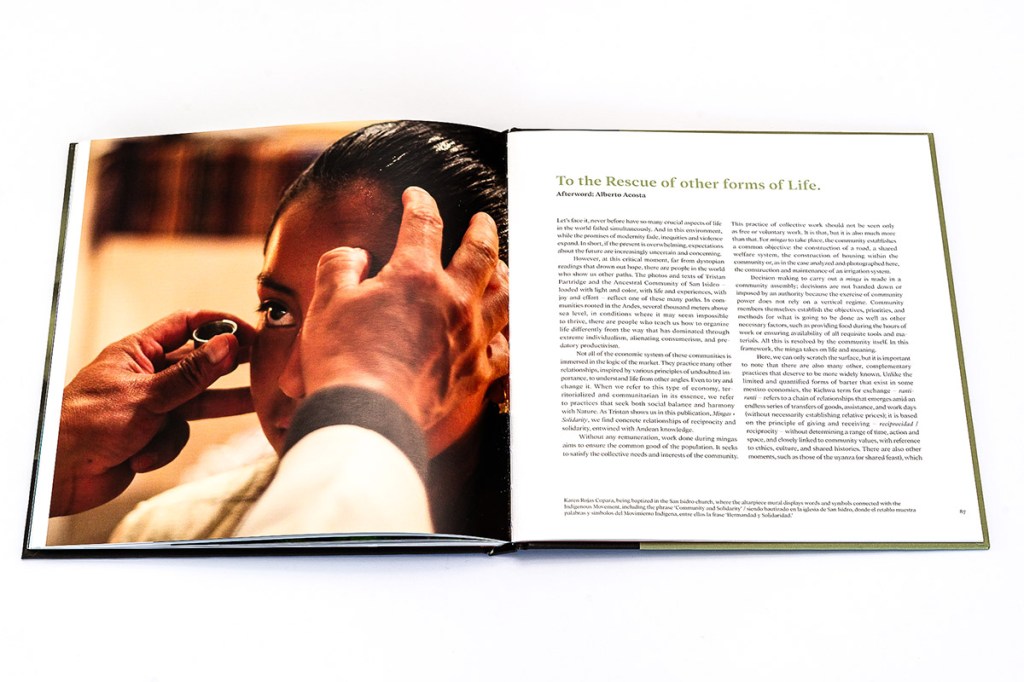

To the extent that Mingas+Solidarity is for an outside audience, it is clear by the end of the book that the intention is not to gaze upon the cultural difference of San Isidro with Western eyes. Instead, we are meant to be taking a lesson from it: that there are alternatives to the individualism and consumerism that dominate much of the contemporary world. As Ecuadorian grandfather, economist, and professor Alberto Acosta writes at the book’s conclusion, “However, at this critical moment, far from dystopian readings that drown out hope, there are people in the world that show us other paths.” Indeed, as a sociologist who studies volunteering in the American setting, I’m inclined to agree with Acosta. We, in the United States, in particular, find ourselves at a time at in which the ideals of democratic participation, civic engagement, and mutual aid are being severely challenged. It would benefit us, at this moment, to learn from the minga.

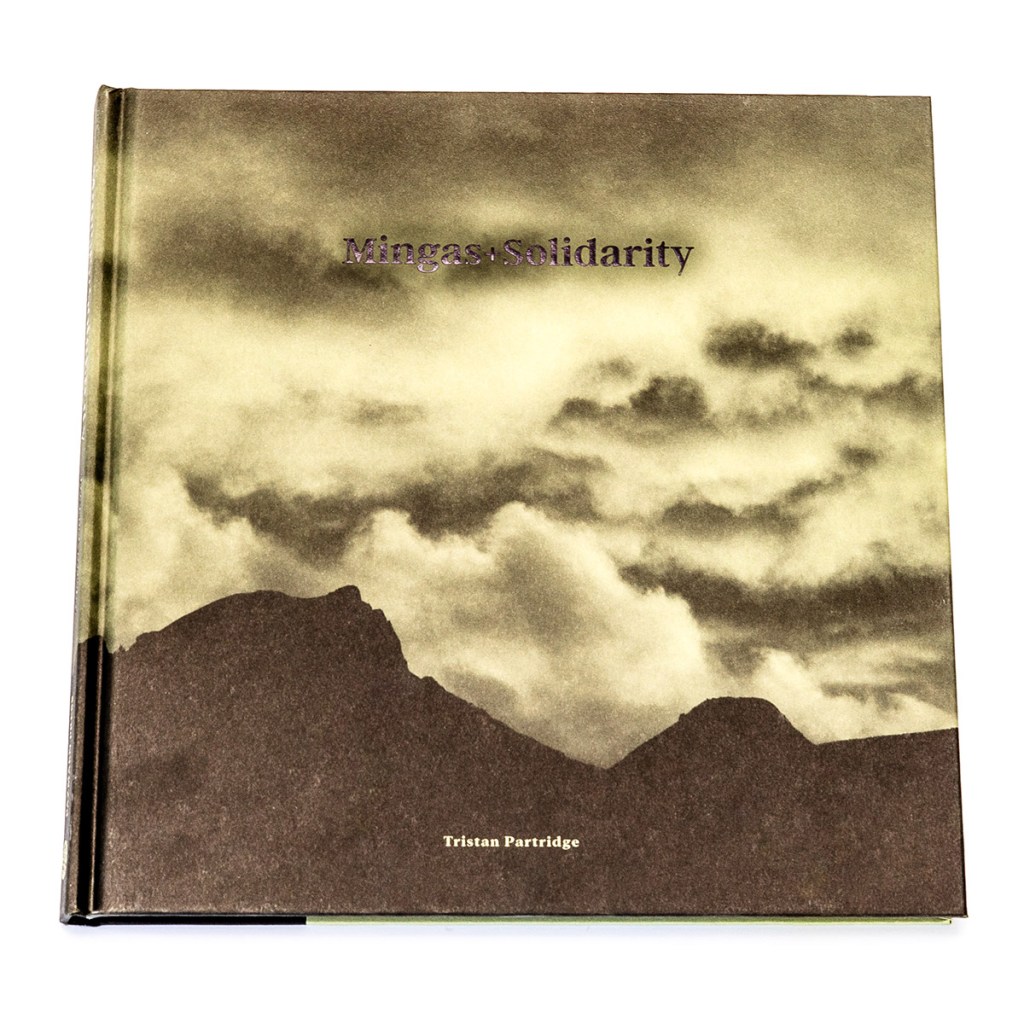

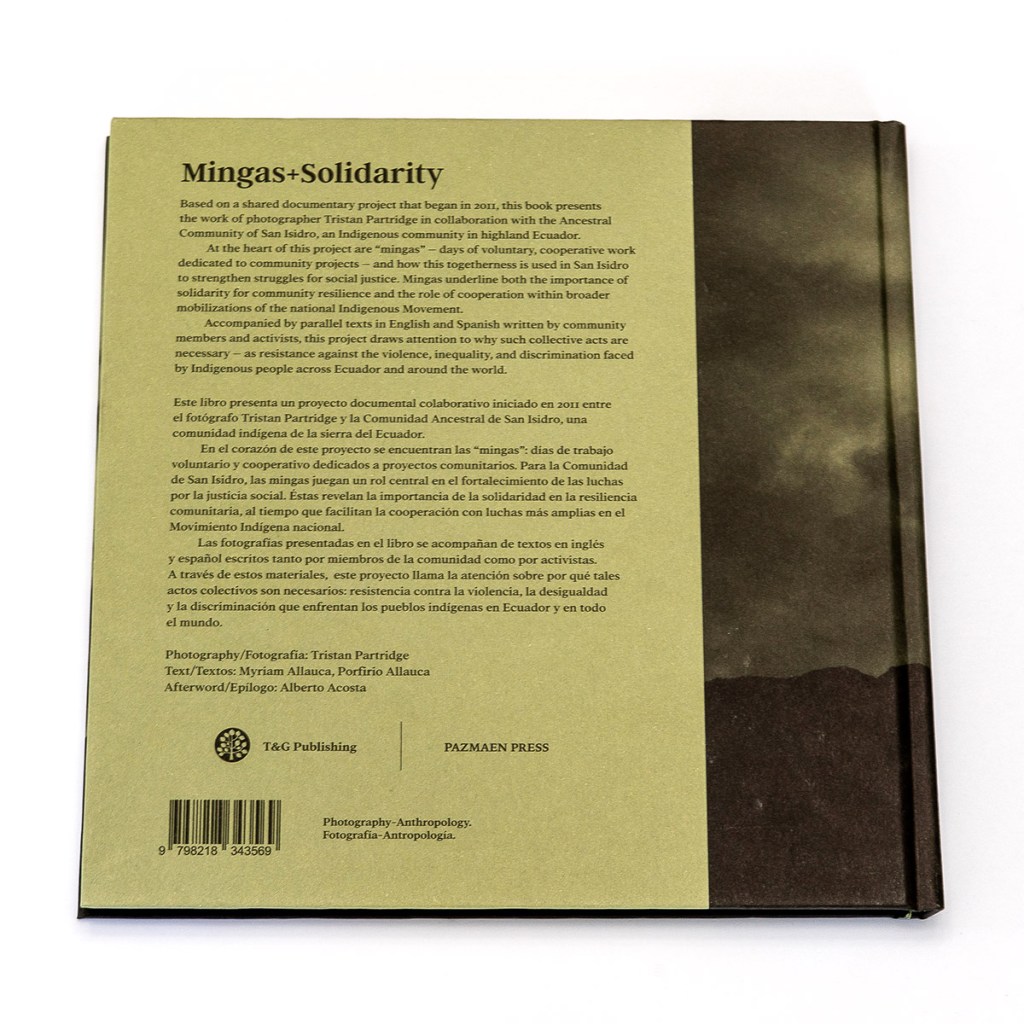

Mingas+Solidarity is one of the most compelling and thoughtful photobooks that I have had the privilege of reading (top three, I’d venture). The book is well organized around a central concept with a timely thesis that is developed through a combination of photographs and text. It was produced with high quality materials, including a very tactilely satisfying hardcover and 100 glossy pages.

Matt Schneider is a professor and visual sociologist in Wilmington, North Carolina.

**Net proceeds from the sale of this book are donated to Indigenous-led organizations in Cotopaxi, Ecuador.

____________

Tristan Partridge – Mingas+Solidarity

Photographs: Tristan Partridge

Publisher: A cooperative project with T & G Publishing

Text: Myriam Allauca, Porfirio Allauca

Afterword: Alberto Acosta

Design: Gianni Frinzi

Printed hardcover; sewn binding; 9 x 9 inches; 100 pages; ISBN 979-8-218-34356-9

____________

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment