Review by Brian F. O’Neill ·

The concepts of both space and place are widely used in our vernacular. Both are also often used in photographic projects drawing on the documentary and landscape traditions of the field. However, while the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, the distinctions between the two are instructive when deployed analytically and aesthetically. Spaces are defined from a physical, even cartographical point of view, with recourse to quantitative measurement and the detailed description of physical features. Contrastingly, place is particular space. Places are spaces defined by their coordinates, yes, but not only. A concept of place points to the unevenness, not just of the terrain between points on a map, but cultural tendencies, languages and dialects, traditions, experience, emotions, and histories. It is this more expansive, yet specific dimension of space that concerns Norwegian photographer Ole Brodersen in his recently published book, Imagine a Place, released through Aye Aye Press in 2025.

We can start with where in space Brodersen works: Lyngør. Indeed, this is precisely how the reader experiences it – a spot on a map, here displayed on the aquamarine endpapers of this tastefully bound book, completed with a blue canvas cover specked with a few points of glitter that reflect variously in different light that is reminiscent of, perhaps, a few flecks of snow or sea spray hitting a wool sweater in winter. These design choices are no accident, as every aspect of the project has been carefully considered, and furthermore, Brodersen has prepared a number of different special edition books made with sail cloth covers of different sorts.

But, where is it? Situated as a series of islands making up an archipelago in Southeast Norway, the place looks out into the North Sea. Beyond that lies Denmark to the South and Sweden to the East. To the Northeast, about 200 km away lies the capital of Oslo. Lyngør is characterized by cold, icy winters (it is slightly farther north than Juneau, Alaska), but pleasant summers, which make it an increasingly popular tourist and retreat destination (although, as the book reveals, the history of tourism goes back to about the 1930s).

Now, let’s get to Lyngør, the place. For one thing, it is what could be called photogenic, and resultingly, Lyngør has been photographed before. Idyllic white and red houses emerge in rows lining the banks of the islands, amidst a landscape of rock outcroppings and trees. Blue skies above and blue water below. Indeed, it was photographed in the early 1900s by artists and tourists, when it became known for its summer weather and its particular atmosphere, seeming to have eschewed certain urban problems and a degree of the hustle and bustle of modernity: we are told through the essays contained in the text that it was something of a little Tivoli (although not the subject of extensive garden and design like Villa d’Oeste), existing as a locale of respite, with “untouched” nature. Adding to its present charms are the ubiquitous boats, because, well, that’s how one gets around. It’s carless, in fact, and people move around the little islets to run errands and see friends, have a glass of wine, and even go to work on the mainland, going first by sea, then Volvo.

However, encountering Lyngør in Brodersen’s Imagine a Place is a contrast to the ways in which the place has recently been seen and described. As the book opens, we first see the water and sky, as if on approach. Then we arrive and it seems to be a dark, foggy dock, perhaps as night falls. Then in the first of several large double fold out pages, we see Lyngør’s famous feature: the lighthouse, visualized in the depth of night amidst a rocky shoreline.

Where are the beautiful rows of houses and blue skies? Brodersen has chosen to render his vision of Lyngør in detailed monochrome, and as we move into more of the book, we start to see these houses, the people, and their practices: from beekeeping, fishing, to home repairs, and more. A hammock and some sail cloth tarpaulin dry in the late evening sun, crayfish wait, tied up to be used as bait, and a boat sits covered in snow, fallen into disuse.

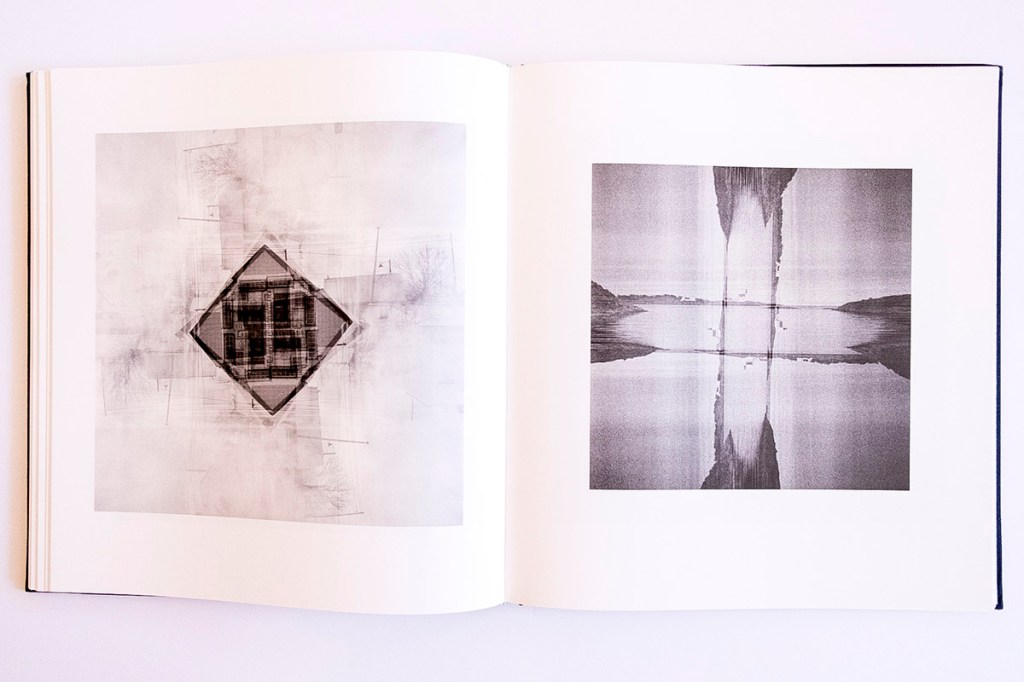

But as the reader moves past this brief inventory of Lyngør, Brodersen signals how the story will become more complex with his multiple exposure images that fold out across three-page-spreads: trees and windows intersect the horizon as the distant shoreline homes seem to be bumping into each other, pulled this way and that by some unseen hand. The foreground offers a little respite for the eye, as picket fences and yards are quieter, but it all forms a rich tableau of elements, jostling for space. Such symbolic imagery succeeds and benefits from, not only detailed observation of the book itself with its high-quality printing on pearlescent white paper, but from the book’s texts as well, which have been commissioned by the artist from a variety of journalists, scholars, and curators, making for rich reading material in multiple registers. The expense of this project was put to good use in more ways than one.

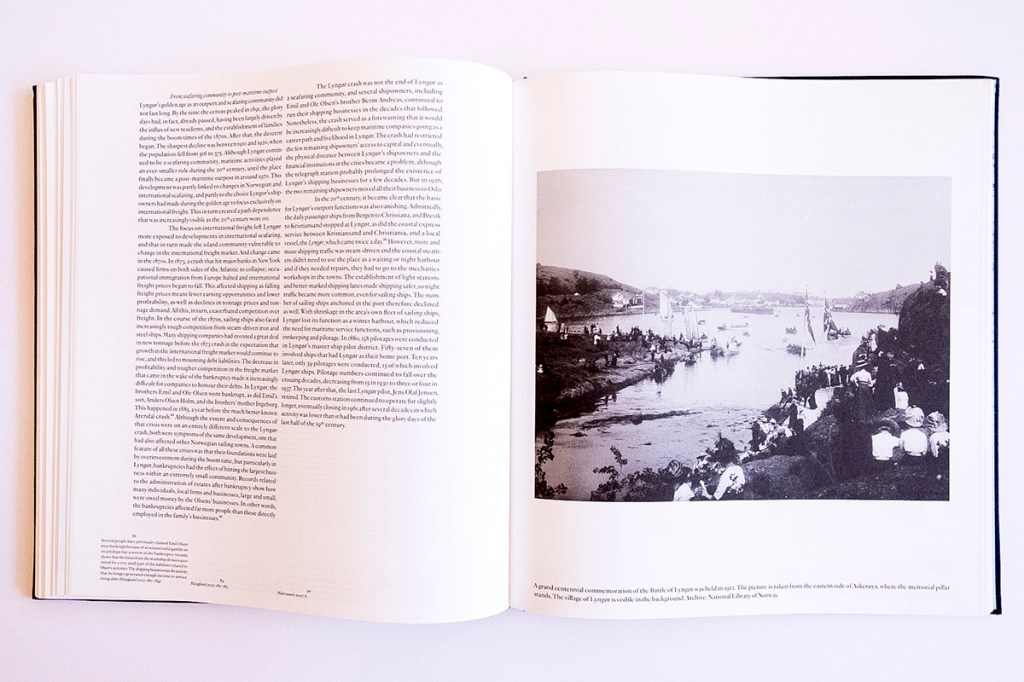

For example, the detailed essay by Håkon Haugland is a serious work of historical research that is both critical and sobering in how it recounts major events from the past 500 years in the region and it helps tremendously to give a deeper understanding, not only to the images themselves, but the sequence Brodersen has chosen. It actually illuminates both the themes of the images, and provides coherence to some of the project when taking the image and text elements into consideration as integral, rather than independent works.

Haugland’s main concern is that “Lyngør is full of myths.” The first of these, I have already touched upon: a place of idyllic respite, which he notes is even mentioned by photographer Andres Beer Wilse in 1934 when he called it, “a little Venice,” after a visit. The second concerns an idea of the glory days of “the age of sail,” when Lyngør was one of the prominent outports in its region as the world saw steady increases in globalization and the maritime economy was central to that project. The third myth he unpacks is also closely tied to the present and one that we see weighs heavily on the mind of Ole Brodersen in his own writing at the beginning of the book, and which is evident in his choices concerning the imagery – he is worried about a community in danger of losing its identity. Haugland’s message aligns with Bordersen’s when we take into consideration that, to imagine a place, means both to try to grasp these myths and why they exist, but also to see how a place is never totally defined by its myths, being subject to outside forces as much as it is in the hands of the people who live there in terms of how they go about their lives and deal with global patterns and markets.

As Haugland deconstructs the myths, we learn how Lyngør has hardly been “untouched.” Its very existence today is in part thanks to a number of industrial operations, first with transnational logging, then as an outport. In its outport status, he explains it was rather exceptional. The island was too small to be a true port in the sense of having a mature and extensive shipbuilding trade tied to merchant capitalism. But it was the largest of its subsidiary type, whereby ships could wait out storms, a degree of repairs could be made, and related occupations, like innkeeping, fishing, and pilotage could develop. But, as the prominence of the steam engine emerged, the need to stop in Lyngør became obsolete. By the early 1900s, population and industrial decline began to set in, and have cast a long shadow in terms of the island’s demographics.

Haugland also expertly interweaves historical data and even a few archival interviews that had been recorded with residents of this period that reveal themselves to be rather relevant when taking in Broderson’s imagery. In particular, Haugland explodes the romantic vision of the place. As Lyngør was large enough, but not too large, through the 1800s, it was a place for socioeconomic elites and shipowners to live and interlock kinship ties through marriage, making it a “a kingdom in miniature.” The caste system was further distinctive due to, not only labor domination, but the history of gender roles. Haugland explains that, in fact, it was places like this that were sites of the initial women’s liberation movement for Norway, where working class women were sometimes, if not often, in danger of being left alone with young children and little to no income due to, among other things their men dying at sea for any number of reasons. And while Haugland reports that the elites seemed to eventually have moved to Oslo and elsewhere, those interested in the environmental movement and slower living, like Brodersen’s father in fact, came to settle in Lyngør. Today, we see that elite interest has never totally left Lyngør, and today, one of the enduring problems concerns zoning and residency requirements, as cultural elites and businesspeople try to find ways to purchase homes and live for a few weeks a year there, a dimension of the archipelago’s existence that at once makes life possible for the permanent residents, while also threatening certain traditions.

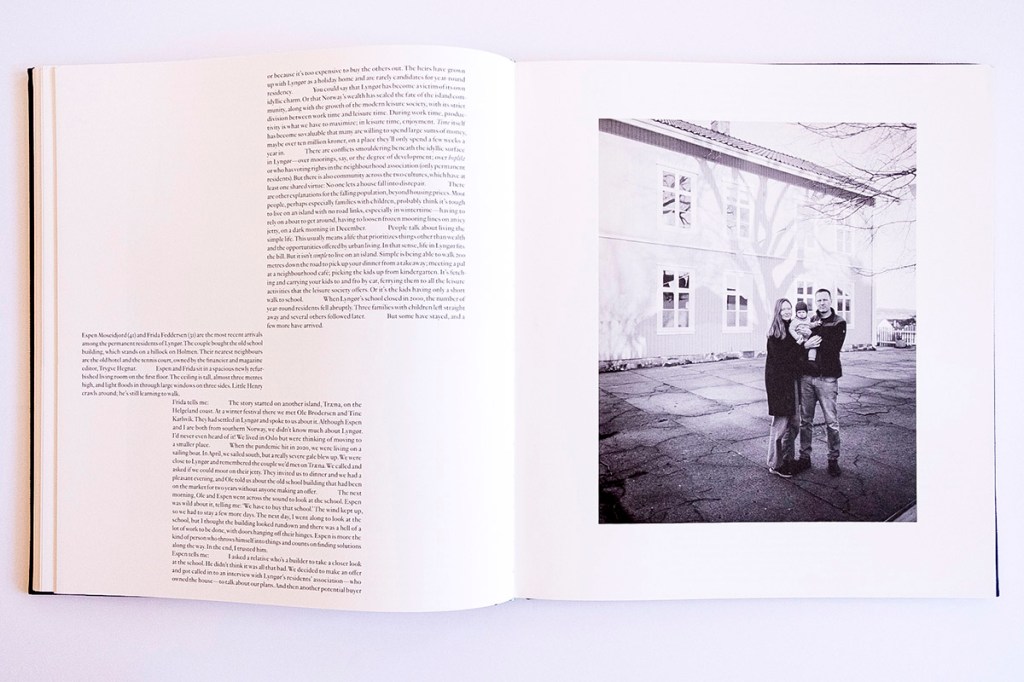

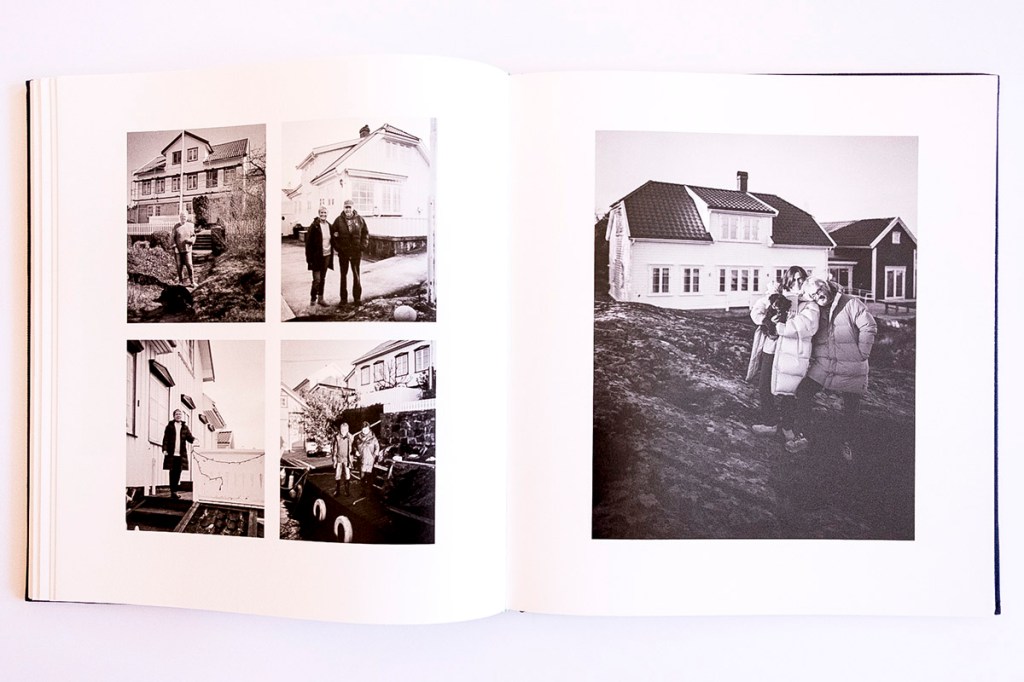

The more journalistic text by Simen Tveitereid develops some of the same themes as Haugland, although it focuses on the contemporary stories and quotidian dimensions of life in Lyngør. The design choices here are logical, as the reader discovers the images paired with the text correspond to the interviews being described with residents, many of whom have spent decades in Lyngør. Still, the tensions Haugland describes are here too. Few have been able to spend their entire lives in Lyngør. Family, work, and other factors pull them away. Yet, the apparently ineffable qualities and community of the place sometimes pull them back. Brodersen’s portraits, made in front his subjects’ and indeed, neighbors’ homes, are environmental portraits whereby he gave them a remote to trigger his view camera. His goal was to reassert the agency of the subjects, and in addition to taking in the scenes as a whole, the images do evoke a certain pensive, but content quality that we often see little of lately amidst the more common contemporary practice of stoic and serious portraiture.

This section is bookended by the more abstract multiple exposure images of Brodersen, and as the portraits close, we get a sequence of square pictures that imitate that of his teacher, Dag Alveng. In them, Brodersen has made quadruple explores by rotating the back of the camera, to achieve geometrical abstractions: of business, of the landscape, and of homes. They seem to capture some sense of the topsy-turviness of the contemporary world under climate change that his more recent projects seek to explore, but they also speak to the turn of history that the project as a whole visually references.

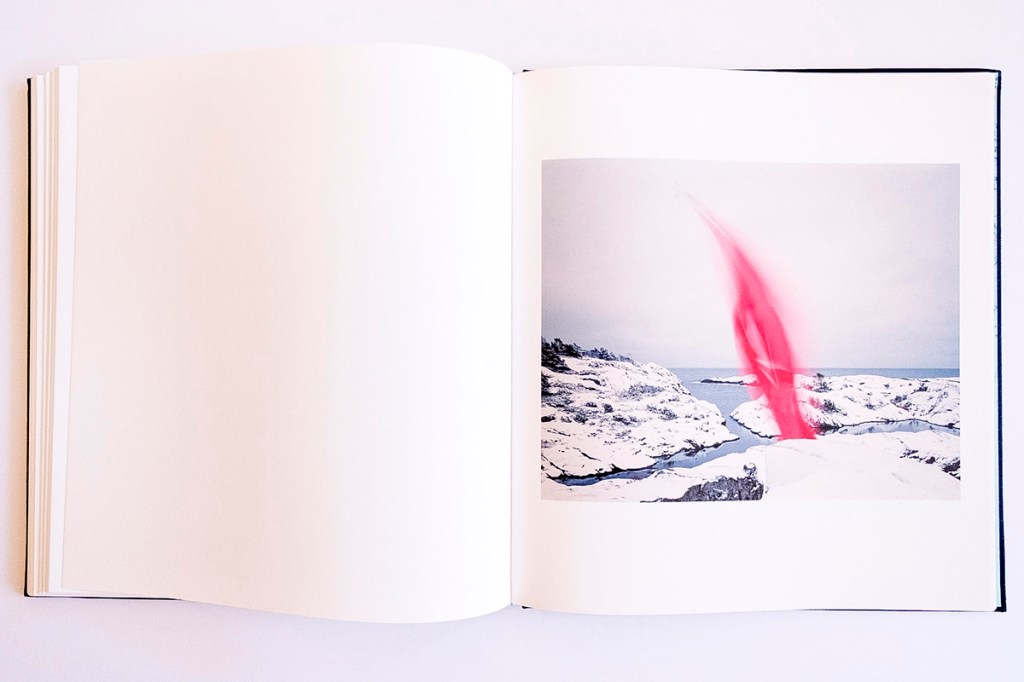

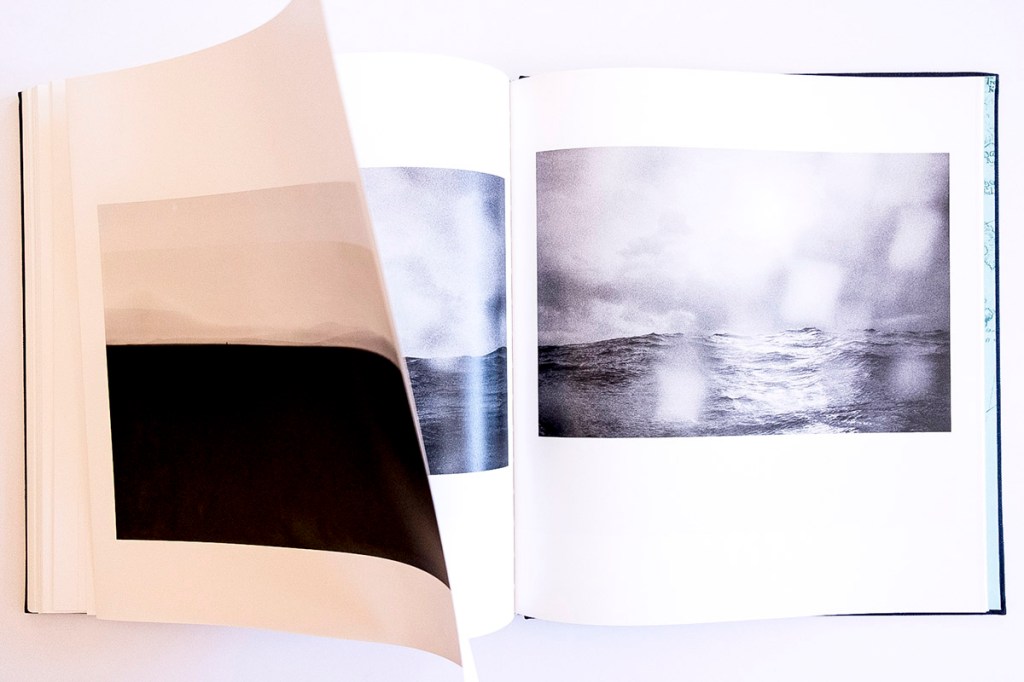

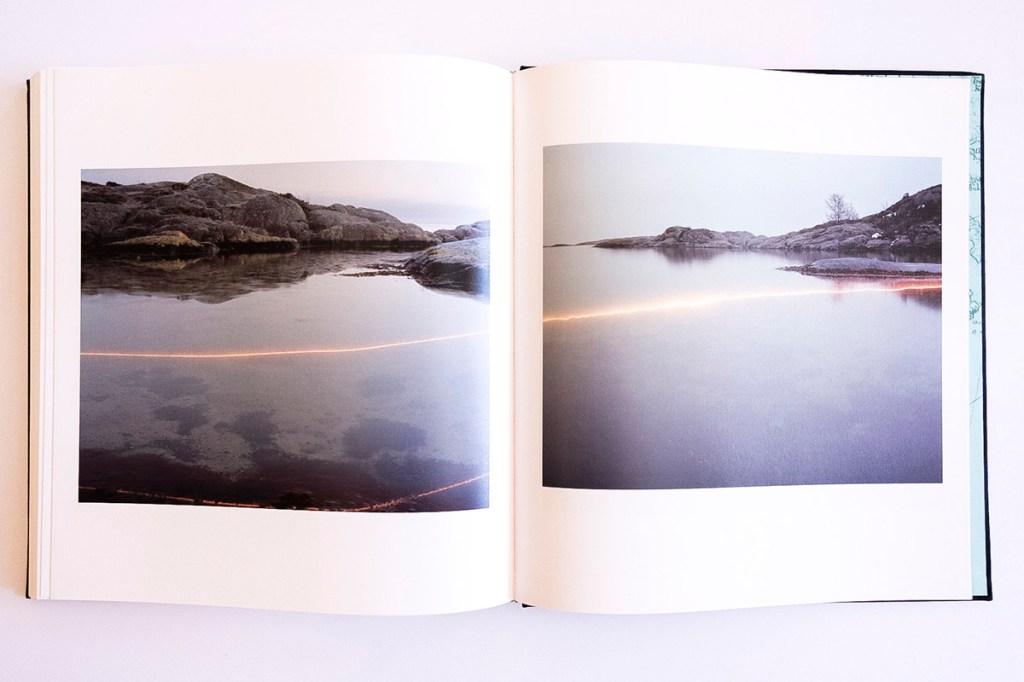

The concluding sequences of images are likely better known to those who have been following Brodersen’s work for the past decade. The Horizontal Displacement series utilizes his technique of shooting from his wooden boat, using a tripod and view camera. All of them speak to the underlying theme of time, whether long or multiple exposures. On the one hand, time here has to do with the mechanics of image making, and the ability to capture something about the movement and fluidity of history in a place that is both a challenge and adventure to live. It is this also that is an encounter with the elements, between humans, nature, and the mechanical apparatus. On the other hand, the issue of time here has to do with horizons. Across the black and white images of the Horizontal Displacement series, as well as the color pictures of the Trespassing suite, we see Brodersen becoming more concerned with the intersection of nature, society, and politics. The Trespassing series in particular utilizes sails, made by his father, in different colors, to create a tableau that obscures the horizon. In the Horizontal Displacements series of images, the horizon was still visible, however distorted. Here, the long exposure of white, green and red sails blanket the future. These are images that ask a question in the abstract, whereas his other images from the beginning of Imagine a Place, sought largely to describe.

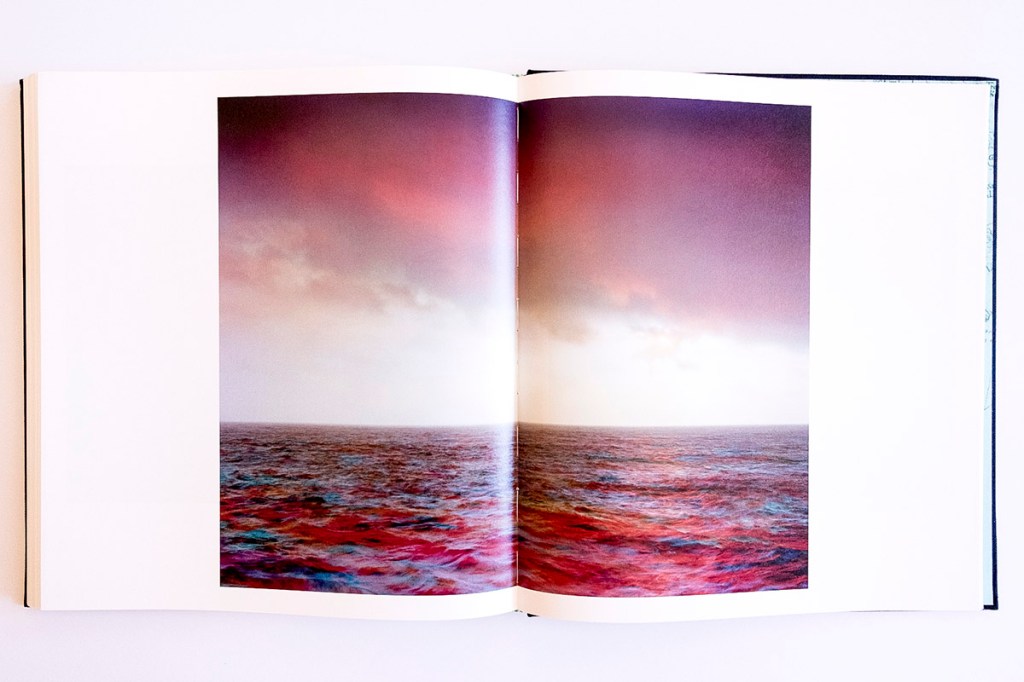

The book then closes with the most striking color photographs of the book project. Here the theme of an uncertain horizon is given a new emphasis, as Brodersen has experimented with filters in some of them, approximating false color photography, a technique used in outer space photography and in certain astrophotographic applications, because of the different wavelengths that are visible through atmospheric layers. The result is that based on the filters that the artist uses, certain other, sometimes less visible layers of light, can be made to be more emphasized. While Brodersen’s use of the method here lies outside of its usual context, and largely offers a conceptual insight, the graphical effect is impressive, while maintaining a rootedness in straight photography. In other words, the images have been noticeably manipulated, but in a way that remains true to Brodersen’s enduring theme of allowing time and circumstance to, in a sense, make their way into the frame. His approach to this produces richly, if oddly, saturated imagery, where the reds and greens and blues are especially highlighted as the colors seem to overlay (there is a certain logic to them that concerns the book as a whole as well, that when first seeing them, I thought they may be black and white images that had been colored) these seascapes that seem as though they could be anaglyphs. This is an intelligent expressive choice by Brodersen that symbolizes how climate change is a question of two moments: one of society’s, and especially elites’ impact (the biologist Dag O. Hessen, who contributed an essay towards the end of the book, recognizes that climate change is intimately connected to class biased resource exploitation, even though he utilizes the term Anthropocene, which has been criticized for painting the issue with too broad a brush, that is, the issue of “human” impact, whereas there is now a wealth of critical literature that speaks specifically to the impacts we are now seeing as being the result of Capital and Man), and the need to look to a horizon of possibility that might take into account slower ways of living, concern for nature, for society, and for being able to repair our communities, our things, ourselves, and our relation to each other in more ways than one. These themes of unevenness, and a degree of unpredictability are further brought to the fore in the Trespassing series, as we observe the fine details of Brodersen’s extended exposures of sparklers and lights moving across the sea, dodging rocks. The images all bear close scrutiny as aesthetic objects, as the level of detail is impressive as one observes stray light like a lightning bolt seeming to hang over the ocean amidst a real attention to color and hue in terms of the tonalities of blues and greens. On the one hand, the climate connection is strongest with these images in a way that to some may seem overly didactic. The less still frames present jagged sparking lines across the water that remind one of the jagged spikes of carbon emissions in so many scientific graphs that represent the increasing dominance of fossil fuels in the economy since the emergence of the steam engine, thus directly connecting to the history of Lyngør, even implicating the place in that history.

The final book’s images, which are night images, put even a finer point on how this book is connected to Brodersen’s thinking about climate change. Amidst the blue-blackness of night, a stream of color emerges out of the corner of Brodersen’s frames: red, blue, green, magenta, gold, and more. Again, we get the scientific connection, although it may at first appear less obvious. What is on Brodersen’s mind? Much of the contemporary discussion of the climate crisis often comes back to “scenarios” and “alternatives,” “possible futures,” and pathways. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, better known as the IPCC, for example, often produces a series of scenarios for any climate predictions that it generates across its mathematical models bases on climatic data observations. As science does not provide definitive, although it does provide likely, answers to our questions about climate, Brodersen here is contemplating these issues in his unique way. Unlike the prior images in the series, where the lights proceed through the frame, here with the multi-colored lines, they stop in the middle of the sea, with the horizon seeming to be nearly gone, receding into the top of the frame as night deepens. It is here in this blackness that we find ourselves as human beings amidst the immensity of the natural world, and the history of the exploitation of it. To say where the trends will end, is to imagine a place in which the devastation can be suspended, like Brodersen’s lights extending into the apparent abyss. However obscure, it is here that we are left to dwell, in the dark tempest of the present and future. We must reckon with the myths and truths of the past, however brightly they continue to burn, and it is at that point that we might begin making new myths, new stories, and ultimately new trajectories to liberate ourselves out from the ones deep within which we once seemed to be so entrenched, however idle(ic).

Contributing Editor Brian F. O’Neill is a sociologist, writer, and photographer based in Phoenix, Arizona.

____________

Ole Brodersen – Imagine a Place

Author: Ole Brodersen (NO, b. 1981)

Publisher, Aye Aye Press (Lyngør, Norway) 2025

Photographs: Ole Brodersen

Essays: Ole Brodersen, Johan Harstad, Simen Tveitereid, Håkon Haugland, Dag O. Hessen, and Simon Bainbridge

Editor: Harald Fougner

Translations: Lucy Moffatt

Image editor: Simon Bainbridge

Design: Modest (Rune Døli)

Typography: Genath (optimo.ch)

Postproduction: JK Mossis AB Sverige

Printing and binding: Printer Trento s.r.l., Italy

Linen hardcover with debossed image; thread-sewn, square spine; 12.5 X 11.5 inches; 156 pages; 98 images; ISBN 978-82-303-7052-0

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment