Review by Hans Hickerson ·

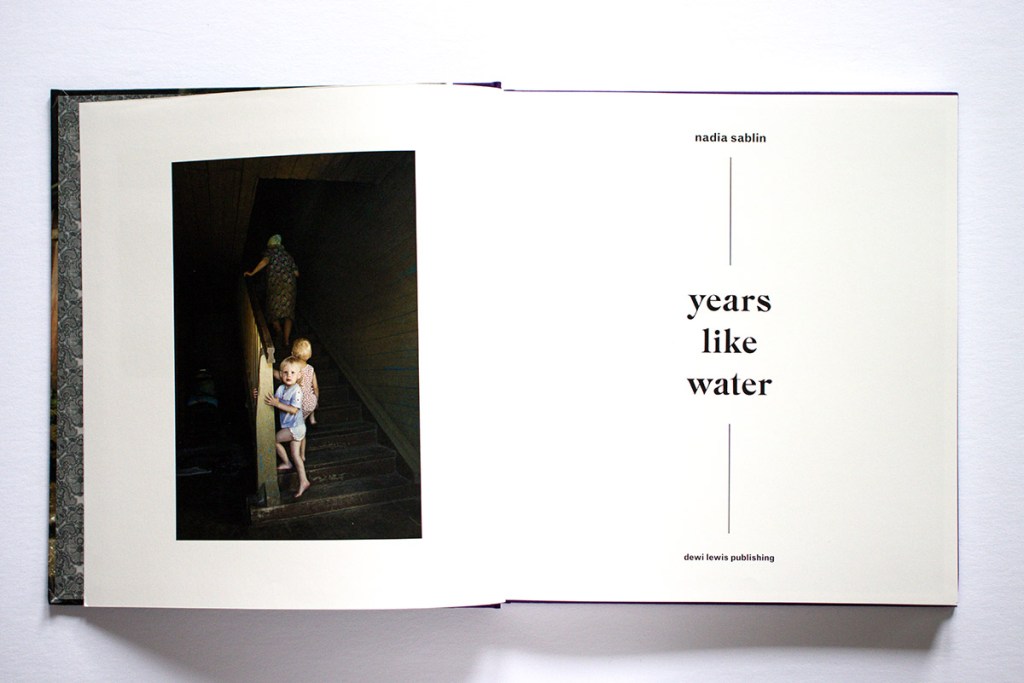

Spending extended time somewhere, getting to know the locals, participating in the community and earning its trust is a tried-and-true approach to completing a photography project and turning it into a book. Nadia Sablin’s Years Like Water is a particularly successful example of this. Like similar books, hers connects us with and helps us understand a place and people. Because of Sablin’s unusually close relationship with her subjects, however, it transcends mere document status and offers an unforgettable tableau of the human condition.

Sablin photographed in the village of Alekhovshchina, Russia, from 2008 through 2021. She had spent childhood summers there until she left for the U.S. when she was twelve, and her family was known in the community. For her project she typically went back in the summer and photographed, but in 2018 a Gugenheim fellowship allowed her to stay for the year.

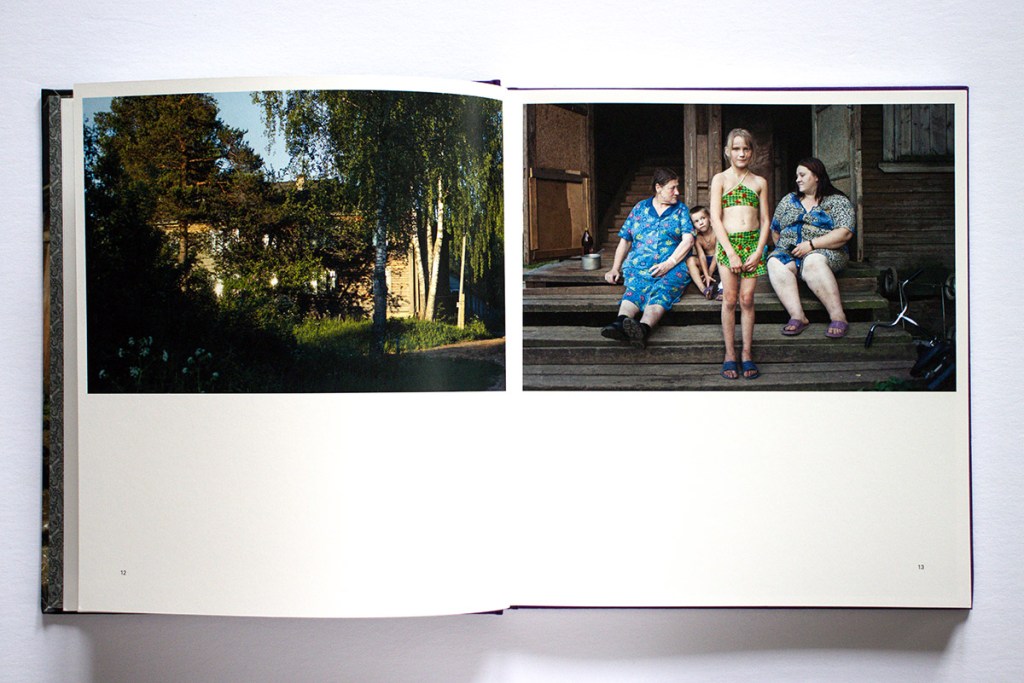

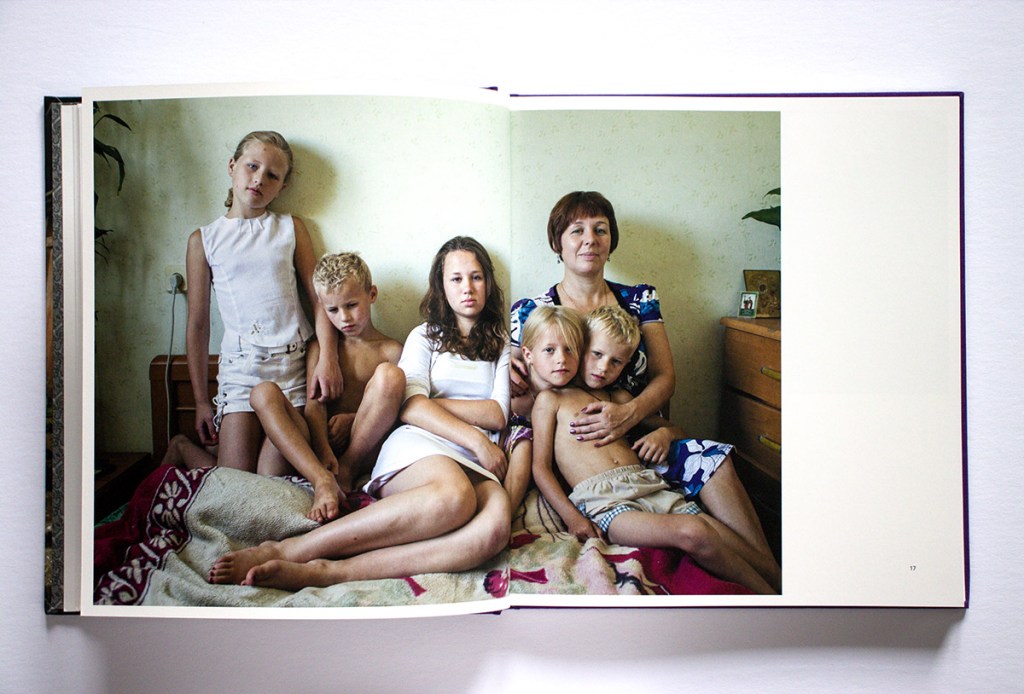

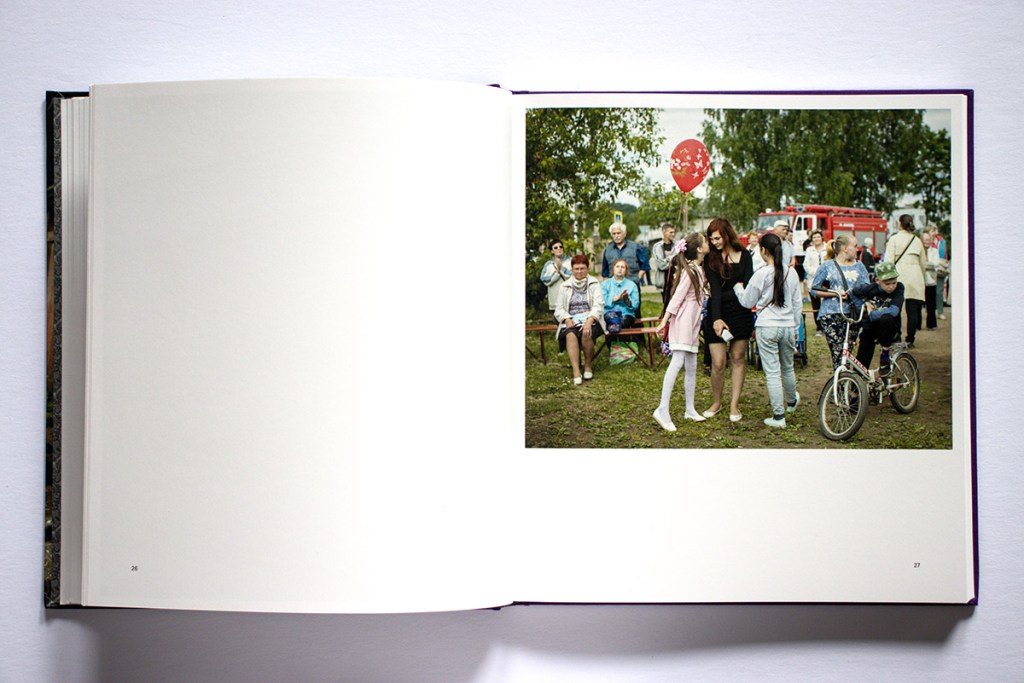

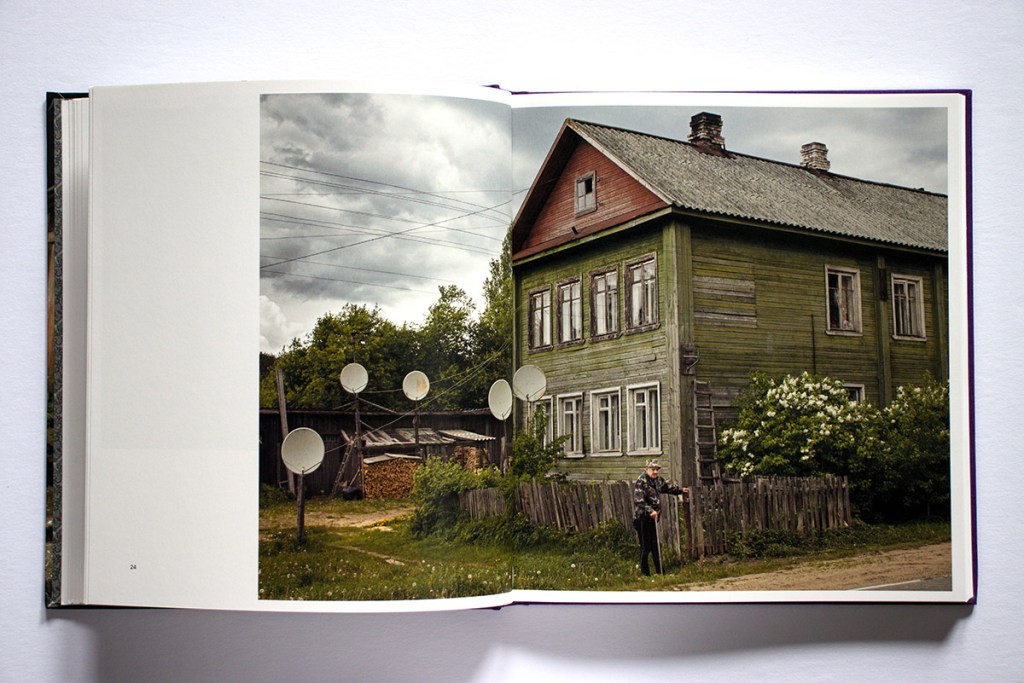

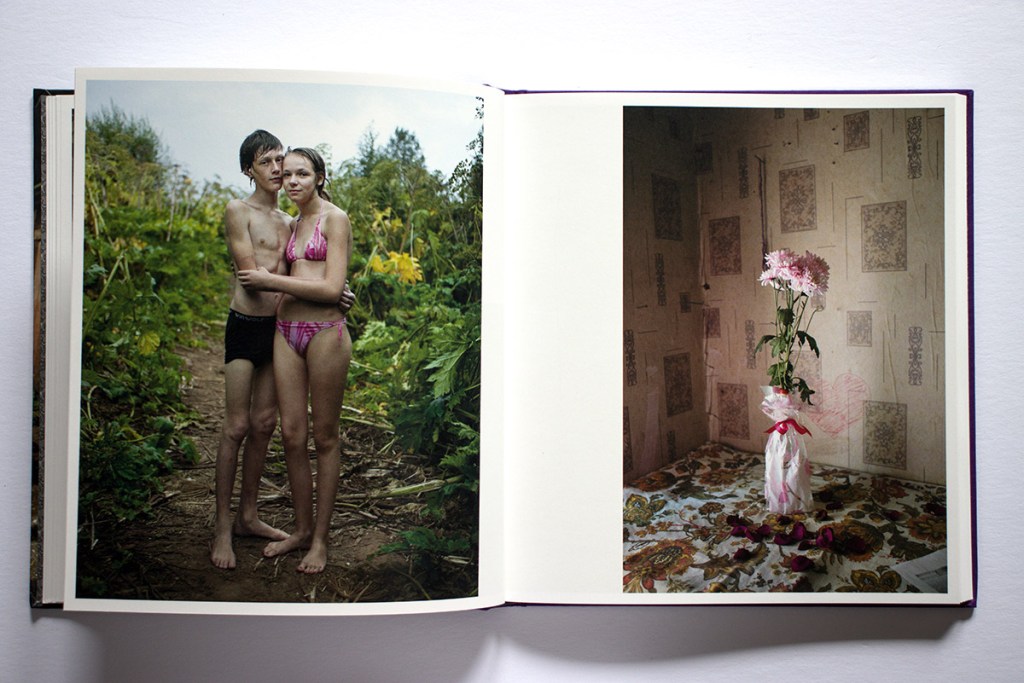

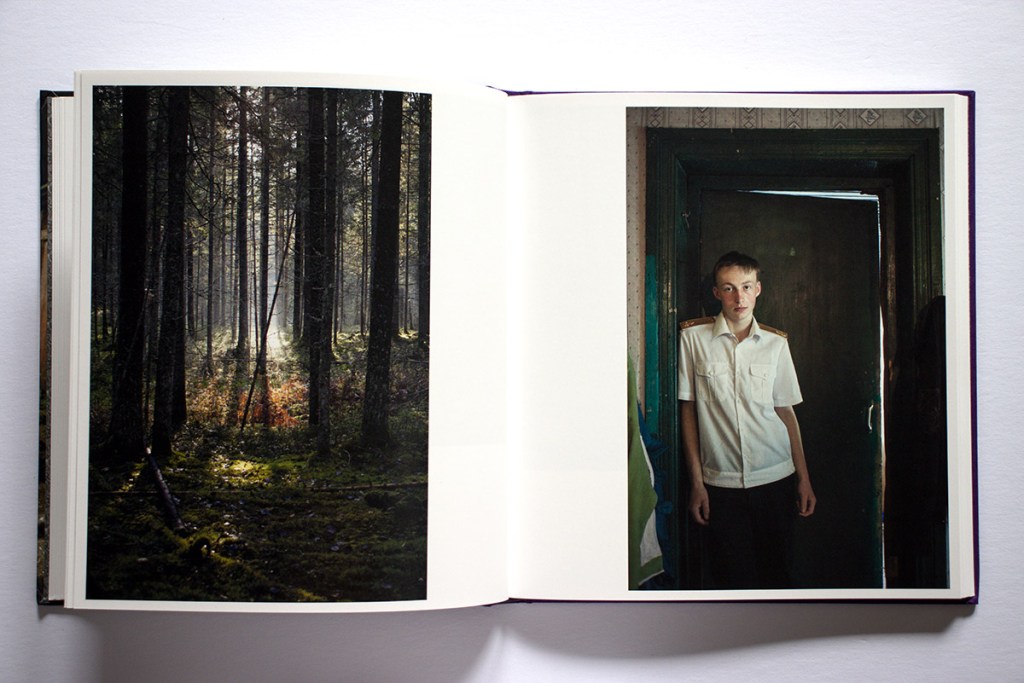

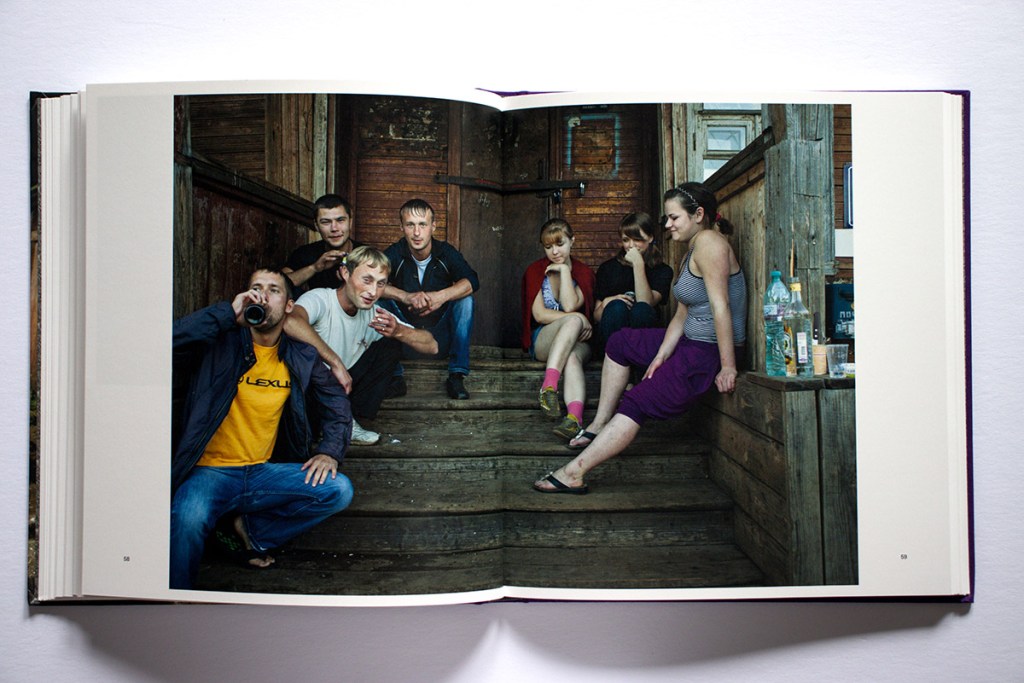

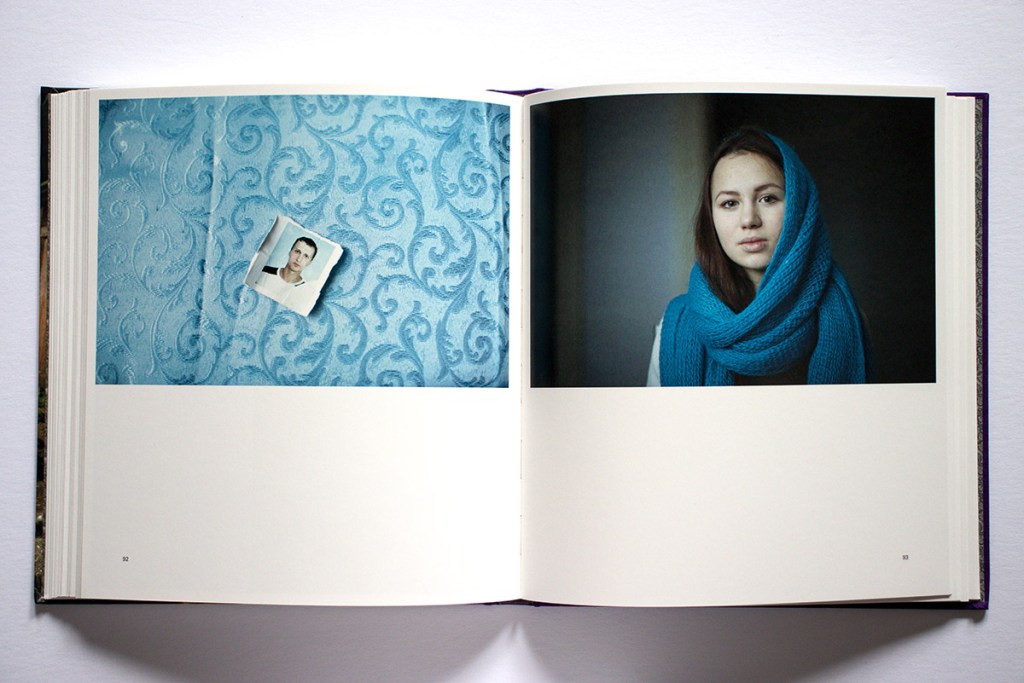

For Sablin, children and young people were easiest to meet, and in the book images of them predominate. There are only a handful of photographs of adults, and they are not the intimate solo portraits that we see of the young people. Interspersed among the photographs of people are photographs of the natural surroundings that help anchor the book in a place. We see a carpet of green on the forest floor, birch trees, ferns, a snowy forest, a pond. There are also a number of images of houses and buildings as well as of details of everyday life: cabbages ready for cooking, an arrangement of flowers, and a back yard scene with firewood, caged rabbits, and a dog. We get hints of the rhythm of village life in the events pictured – a senior dance at the cultural center, the village day fest, teens hanging out in front of the post office, a group of teenage boys pushing a dead car, and what must be a high school graduation.

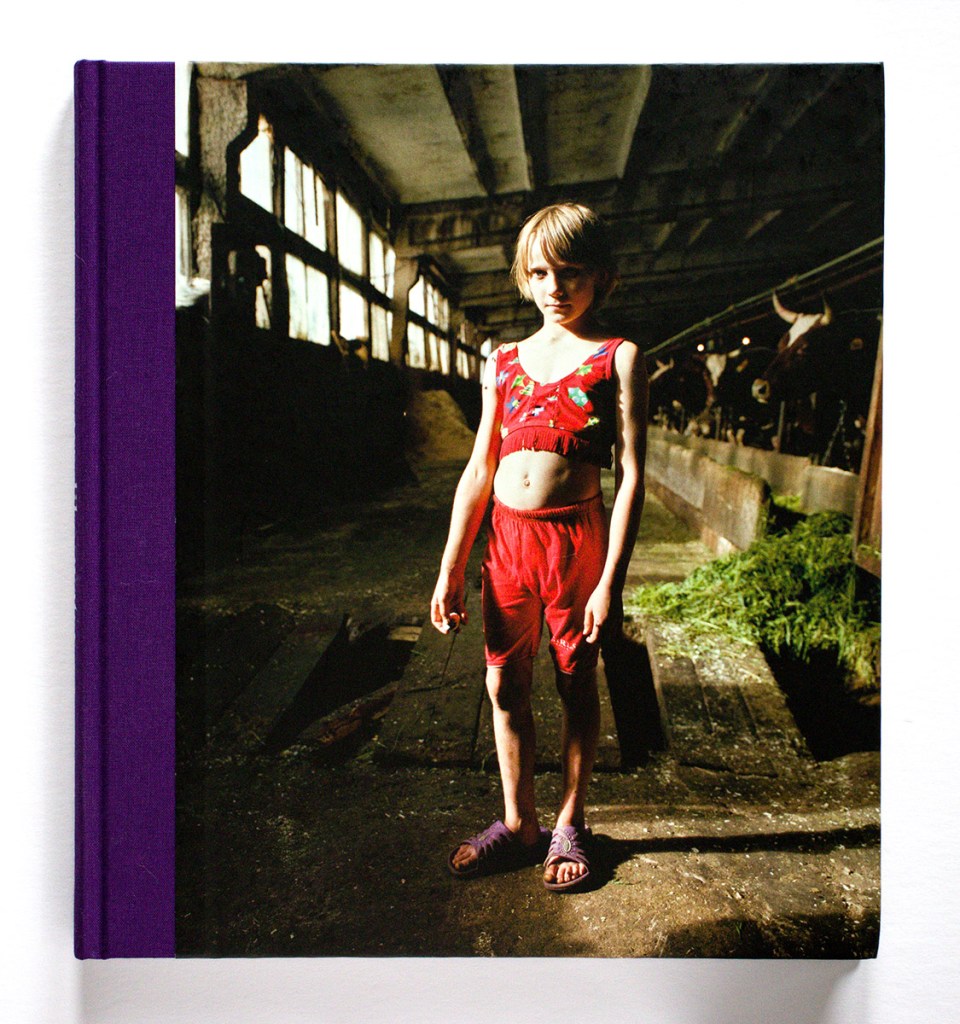

It all adds up to the portrait of a community, at least a community seen through the lens of one photographer. Sablin’s Alekhovshchina looks neither modern nor prosperous. We glimpse a few newer buildings but the houses we see are run down and in need of repair, their simple furnishings mostly handed down from earlier times. Childhood seems to be of the old-fashioned, unsupervised, free-range variety where you make your own fun and grow up fast.

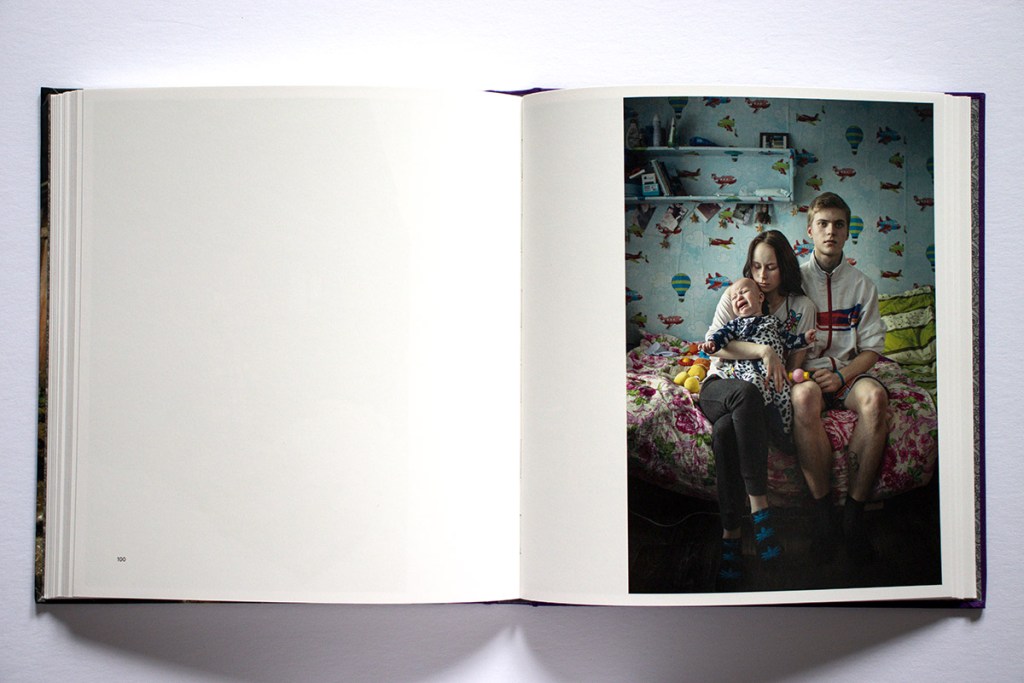

In her engaging afterward, Sablin explains how she met people and became involved in their lives, and she gives us details about some of them. The extended time she spent in Alekhovshchina allowed her to photograph the same people multiple times over the years. We see Vika, the girl in the cover photograph, in 2009 and then at the end of the book in 2019. We see Alyona as a young girl in 2008, as a pre-teen in 2013, as a teenager in 2016, and then with her first child and future husband in 2019. We see Alyosha as a skinny middle school boy in 2009, as a high school cadet of some kind in 2012, and as an older teen in what looks like a sailor’s uniform in 2018.

It is a coming-of-age story. As in villages everywhere, kids play, mess around, grow up, and then become parents themselves, all too soon confronting the long odds of a hard life. After spending time with and getting to know them through Sablin’s photographs, you can’t help but feel for them, especially when you think about what their lives must have become after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. What options will they have if they stay in the village? How will they manage if they seek a better life in the city? Maybe someday Sablin will be able to return and pick up her story where she left off. But for now we are left with her Alekhovshchina teens suspended on the cusp of adulthood, their possibilities limited, their futures unknowable but arguably bleak.

The book is handsomely packaged and printed. It fits together well – photographs, author’s afterword, and then a handy section with small versions of the photographs along with captions. Simple and tight. Unlike some photobooks it is not overproduced. It does not overdo itself trying to impress you with flashy features.

Sablin doesn’t explain the book’s title, Years Like Water, but for me it needs no explanation. It is a brilliant comparison: how easily we go through life, how smoothly time flows around us, how transparent and effortless it seems. And then you look back and the years have passed – like water. You can’t say where they have gone. It’s too late and you can’t go back.

Hans Hickerson, Editor of the PhotoBook Journal, is a photographer and photobook artist from Portland, Oregon.

____________

Nadia Sablin – Years Like Water

Photographer: Nadia Sablin (born in Russia 1980; lives in New York state)

Publisher: Dewi Lewis, UK © 2023

Language: English

Text: Nadia Sablin

Design: Bonnie Briant

Printing: EBS Verona

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment