Review by Brian F. O’Neill ·

On the one hand, many people define cities as the sum of their innovative minds, cultural milieu, and the enterprising spirit that seems to emanate from a place. Another line of insight into the nature of cities concerns the interpretation of their becoming. As historians and cultural geographers have increasingly emphasized, the unfurling of the varied processes of urbanization often points back to Nature. It will come as no surprise then, that New York City, not quite so “modern” as Paris, nor so postmodern as Los Angeles, is an especially apt location to uncover this connection. While the city is known for its green spaces, (like the famous Central Park, or even more recently, the now transformed High Line, photographed in its formerly decrepit state by Joel Sternfeld, now a locale of urban nature and tourism) one of the city’s most foundational elements is water. As cultural geographer Matthew Gandy has argued, the reworking of nature through channeling, sluicing, and guiding flows, has been central to urban and suburban expansion. What we now experience in New York is what Gandy calls a metropolitan nature, a mode of infrastructural existence that creates a sense of integration and cohesion through its engineering out of what is in fact a varied territory that would now largely be unrecognizable to the indigenous peoples, and then settlers, who encountered it just a few hundred years ago.

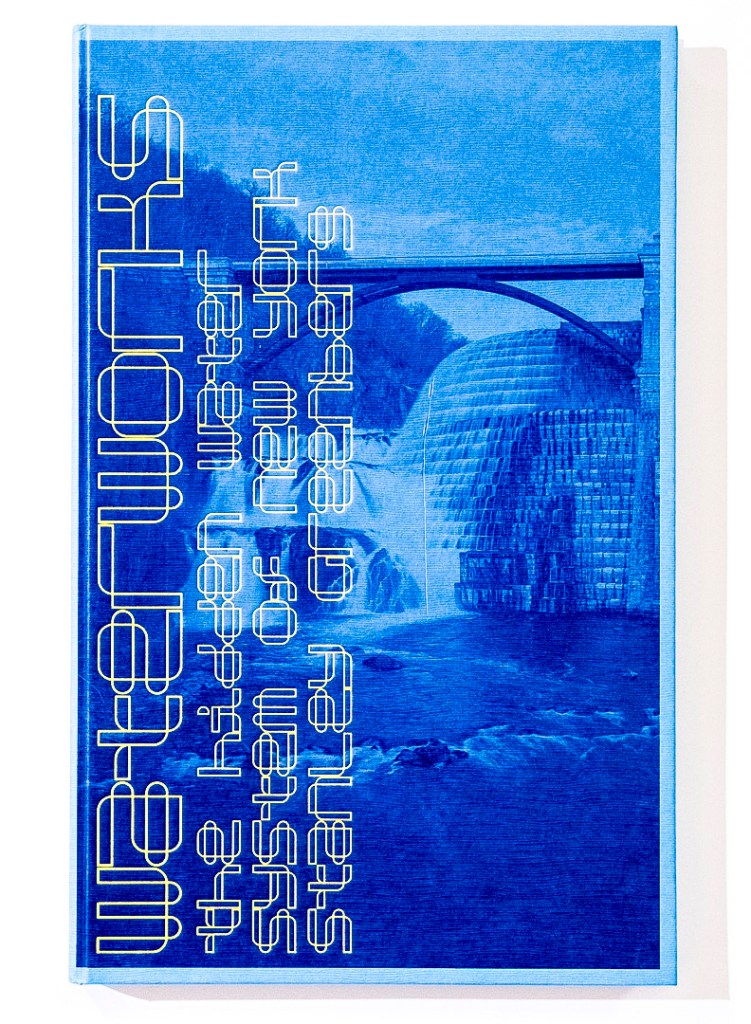

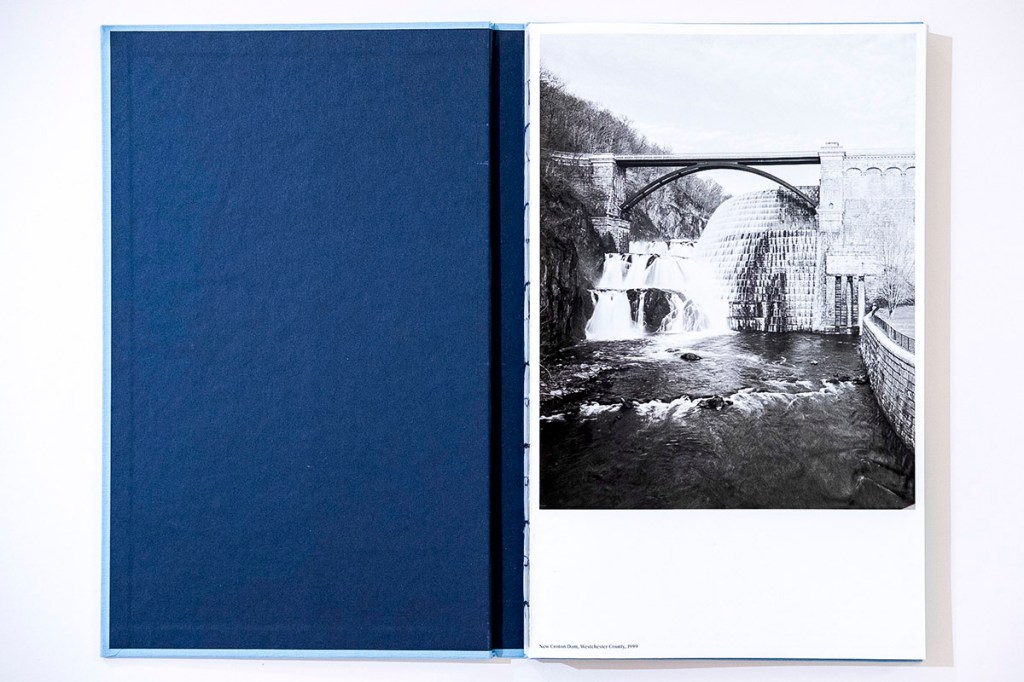

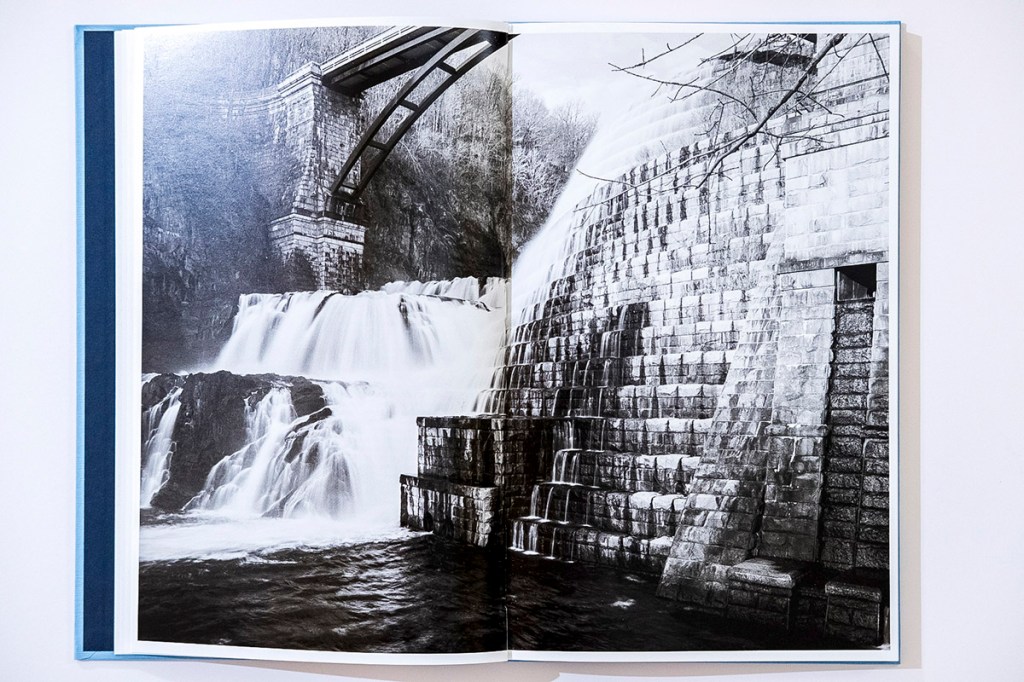

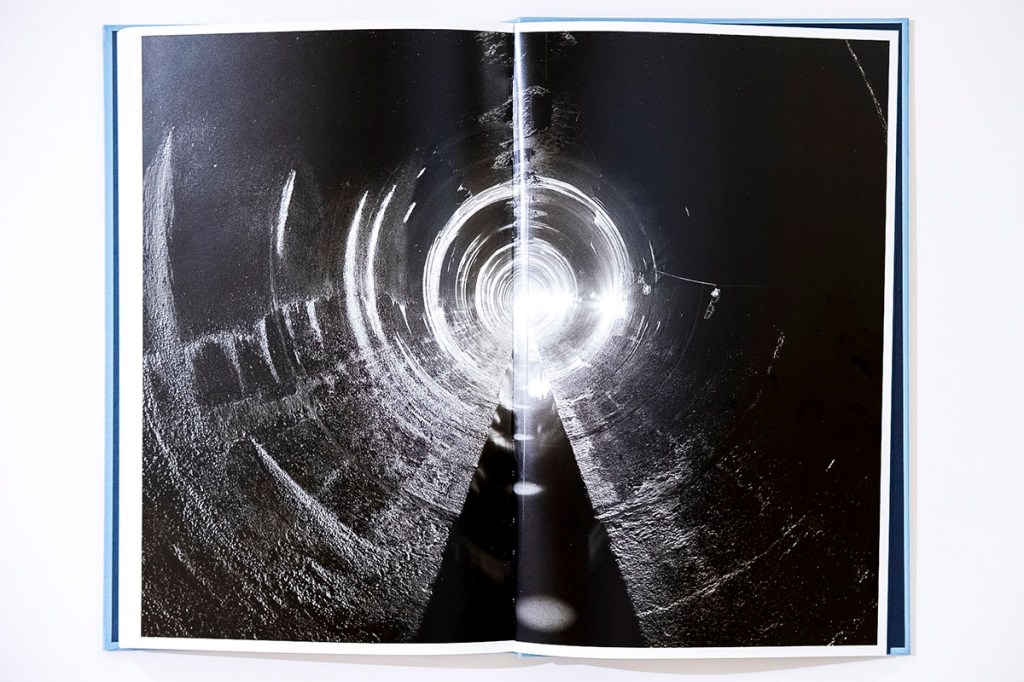

The undergirding of this metropolitan nature is the subject of the reworked and updated printing of Stanley Greenberg’s Waterworks: The Hidden Water System of New York. The original project was published in 2003, but here we see the culmination of Greenberg’s longstanding, and very personal commitment to documenting the water, and sewage, system. The book has been updated with new images and a striking, tasteful design, making it an attractive object to behold and a pleasure to page through (the cover is especially considered, as, beyond the fact that it is blue, it has a slightly wavy texture embossed into it, adding to the sense of a flow). Across hundreds of monochrome images, we take in water as system. Some of this is in the subterranean depths of the greater New York territory (it was no small task to access and photograph – Greenberg reports being rejected repeatedly by government officials to access sites and he faced problems with the 2003 publication, as his document was seen as sensitive in post 9/11 New York), and some of which is in plain sight.

Greenberg’s use of “hidden” in the subtitle is appropriate both for what images the reader sees in this edition, and for the way that it signals something about his method, one of attentive observation as much as one of considered research. Even as a kid in Brooklyn, Greenberg recalls noticing the conspicuous ever-presence of storm sewers and fire hydrants and brick buildings leading…? Well, somewhere. That question would stay with him. It would be only later, as he developed his life-long commitment to the photographic documentation, and indeed, mapping of the industrial heart of contemporary life, that he began to slowly uncover the water system’s sinews towards what he calls: “a private map.”

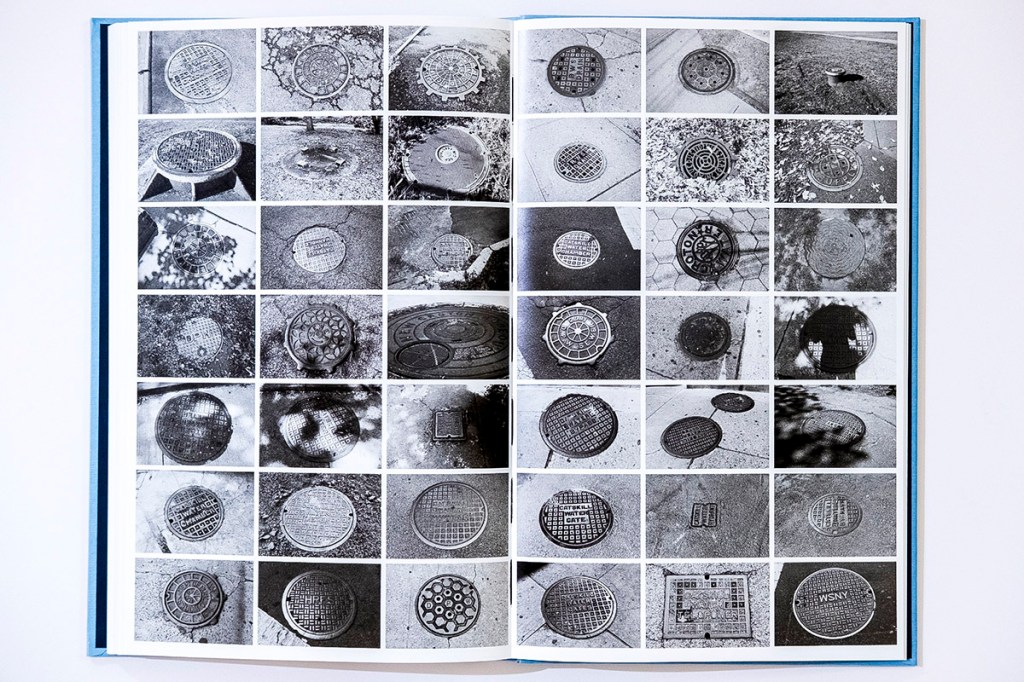

This map of experience, as encountered by Greenberg, unfolds through the text across a number of smaller sub-systems that deal with collection, conveyance, distribution, and treatment. To his credit, Greenberg has not just made images of the particularly photogenic or “wonderous” structures. If there is a sense of industrial sublime here, it remains muted, or at least it retains a respectful distance. Throughout, he shows that he understands how the system works, well, systematically, or we might say, as an assemblage: without one part, another cannot function for long, all of it coming from or eventually returning to nature and the atmosphere. All of this and more are discussed in a brief essay that Greenberg made specifically for the project.

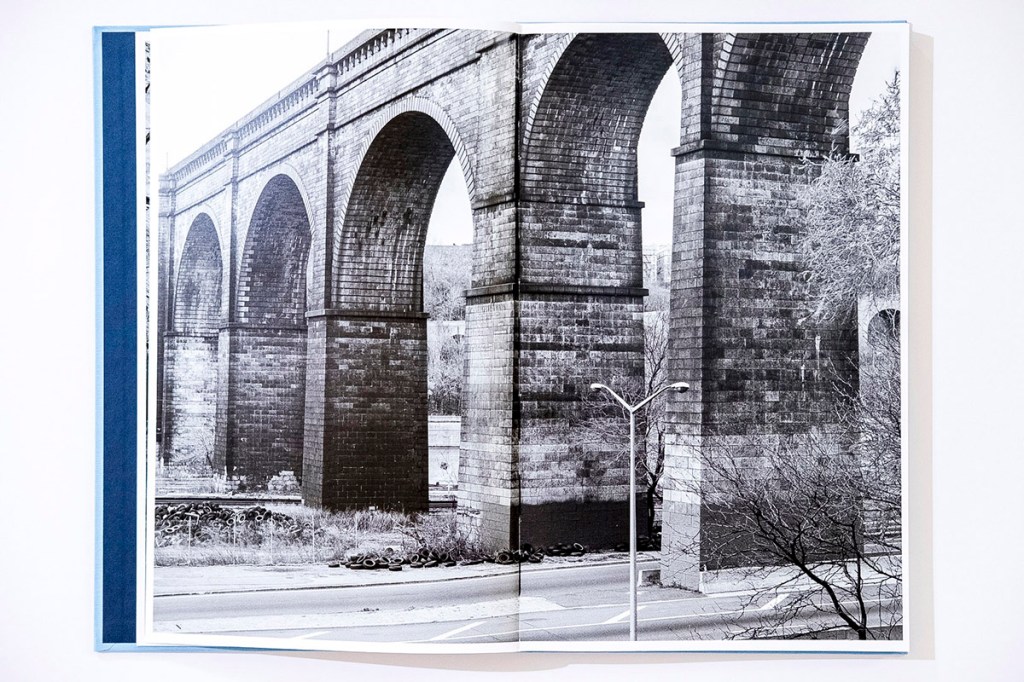

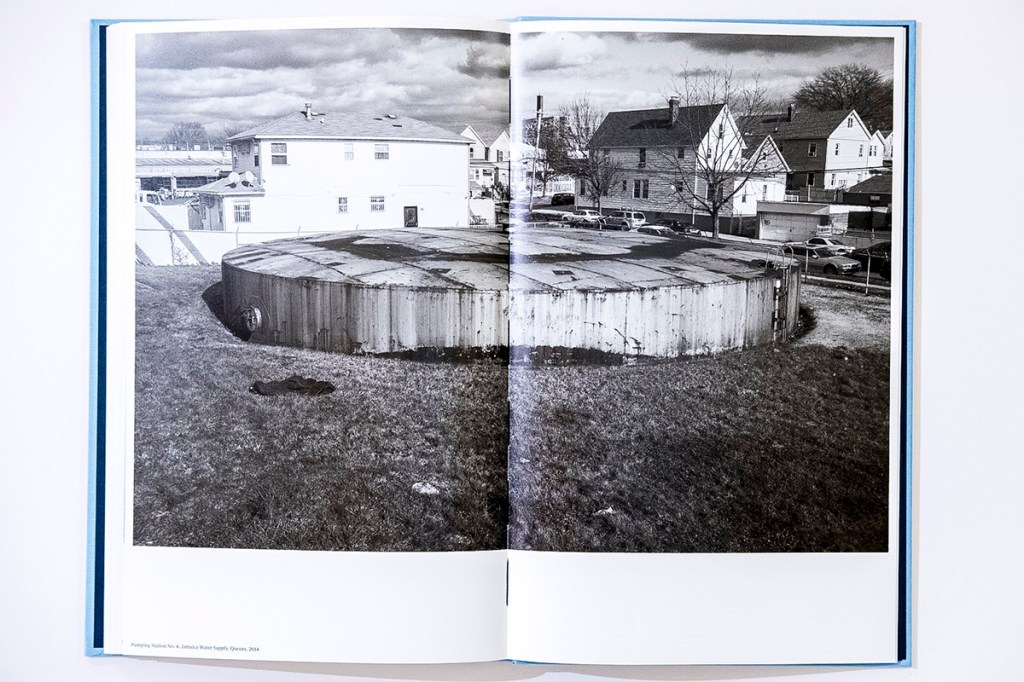

The images themselves are striking monochrome renderings, full of detail even in the darkest shadows beneath the earth. The book spans more than 20 years of image-making. However, without the date and site descriptions given throughout the book, one would not be able to tell which was made when. Greenberg has been dutiful and consistent in his approach, visualizing the infrastructure almost always with what would be considered a normal field of view and at eye level, emphasizing the placement of the human amidst the often-vast landscape. But, he holds to this method for the “intimate” scenes too, where no doubt, he was tucked away in a corner of an odiferous, damp tunnel.

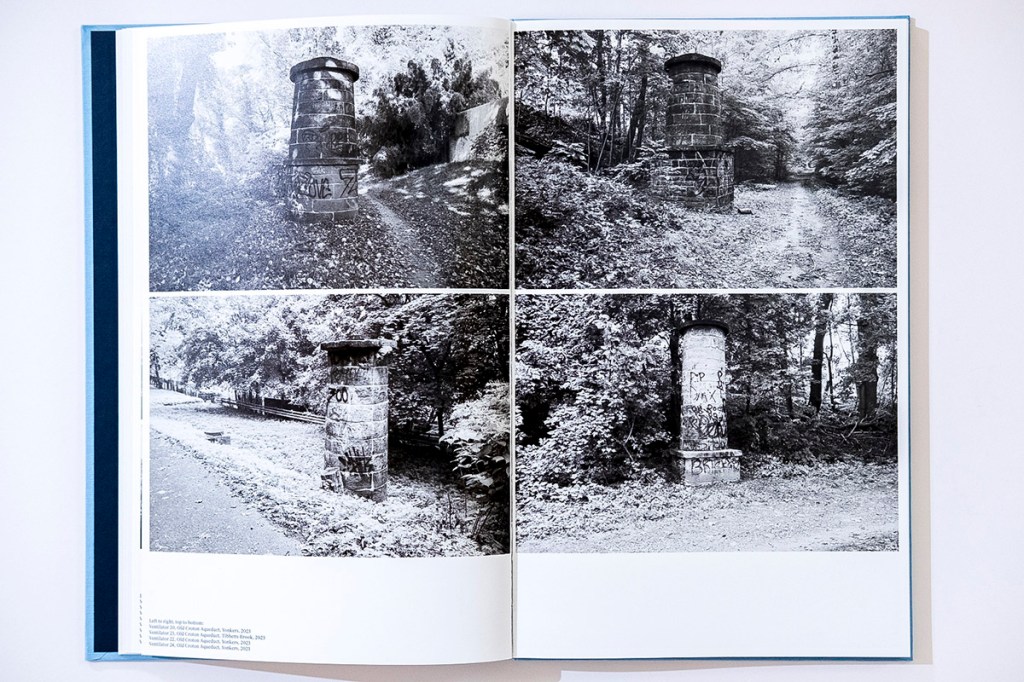

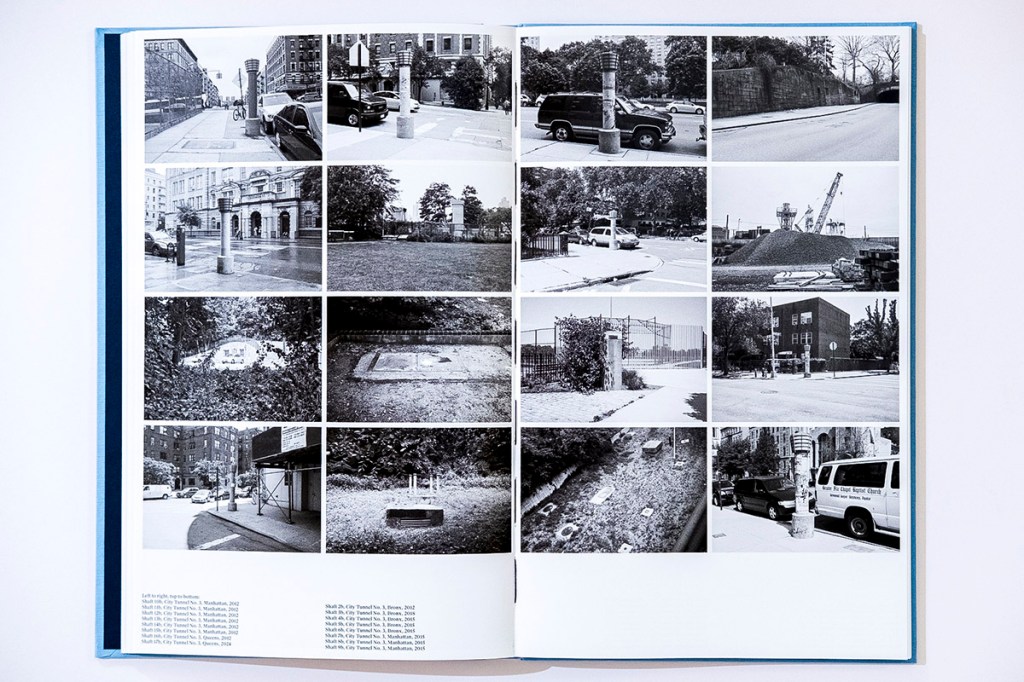

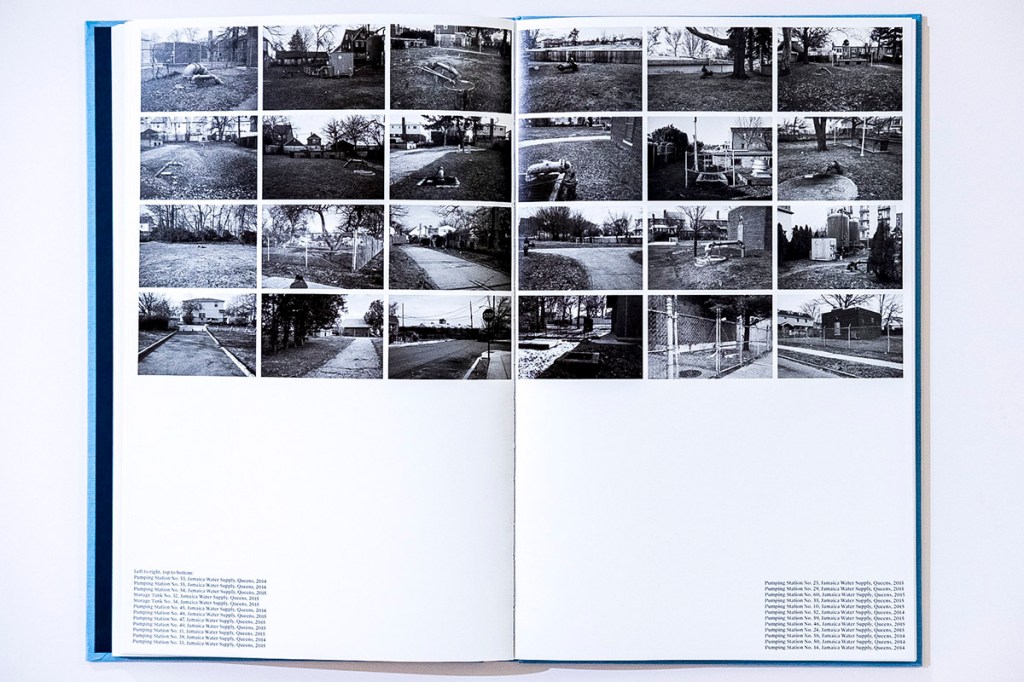

The monochrome palette and precise framing have some formal elements in common with the famous typographic work of Hilla and Bernd Becher. Yet, while Greenberg’s scenes are often people-less like the Becher’s well-known images of water towers and factories, they are still scenes. If Greenberg’s images are less immediately haunting, they gain their affective quality in other ways. We never lose sight of being in the world with Greenberg. Life is happening in and around the city. If there has been postindustrial decline, the water system, so vital, cannot so easily be discarded, removed or forgotten by society. We see old tires sit along a railway and road at High Bridge, Bronx and Manhattan, 2000. People attend church and go to work amidst Shafts 2b through 17b, Tunnel No. 3, Manhattan. Wastewater is flowing through Brooklyn and Queens. Pumping Station No. 4, Jamaica Water Supply, seems to have landed ominously in Queens on a residential street. Ventilators stand, graffitied and bird poo bedecked, as sentinels along the Old Croton Aqueduct in Yonkers. Old and new, the infrastructure channels, but also permits innumerable other flows of life, however apparently marginal.

Adding further visual variety, Greenberg expertly reintroduces the human to the typographic concept with his interspersed matrices of pages of images (4, 16, sometimes more) arranged across a spread, of, for example, the shafts and city tunnels, going often unnoticed but still intimately a part of the urban life of New Yorkers. These scenes especially speak to the theme of metropolitan nature. Human elements are here “interacting” with “the natural.” Engineering exists with people and nature. As the reader experiences the organization of the book as a reconstruction of the flow of water from the hinterlands of the city’s several reservoir systems towards New York, New York, and its boroughs, Greenberg establishes the interlocking of society with the systems that are surrounding us.

***

As I continued to return to the book, I reflected on the potential meaning of Greenberg’s term: “private map,” as used in describing this project. On the one hand, it seems at least ironic, if not nonsensical, due to the fact that the images are presented in a book, for consumption, if you will, by the public (or at least, the photobookish variety). Yet, this is always the tension with photography. A photograph is largely a thing that is made privately, sometimes even secretively (Greenberg even reports he was taken to some locations by friends, clandestinely), formulated within the darkened apparatus of the camera, whereby the artist brings to light images and selects subjects from the world for not always very clear reasons. Still, for Greenberg, while there is a literal map included in the book, the other kind of map that is operating here is what might be called a deep map, to use William Least Heat-Moon’s term, that is, a way of approaching the landscape that seeks to connect facets of cultural history and geography with the interpersonal and biographical. Indeed, in the 1980s, Greenberg held a government post at the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), where, as he reports, “I got to see the water infrastructure up close, mostly where the water mains had broken.” At some point, he became knowledgeable of, and fascinated by, a huge archive of images dating back to 1840 of the system that has continued to provide a source of insight and inspiration for his work. It is foundational and fitting then that in this new edition, we get to see a fuller realization of a lifelong commitment and concern for this most public type of infrastructure. To this end, in a recent interview Greenberg has commented that he wishes that people had greater access to these so-called hidden places: “I’d try to convince them (DEP) to allow more public access to the system so that people are more connected to the water supply and wastewater treatment systems. I think it’s easier to ask for the public’s help in taking care of the system when they understand better that it’s a public resource that they collectively own.”

Amidst so many books, artistic and otherwise, that now approach topics of environmental protection and petrochemically induced ecological decline of all sorts, I cannot think of a higher aspiration. Greenberg’s discerning eye and detailed, systematic approach can serve as inspiration for that kind of collective thinking, and of course for the fine execution of the photobook form that is the result of persistent, yet, patient commitment, and one that is concerned, but never heavy handedly didactic.

Brian F. O’Neill is a sociologist and photographer based in Phoenix, Arizona.

____________

Stanley Greenberg – Waterworks: The Hidden Water System of New York

Photographs: Stanley Greenberg (Am, b. 1956)

Essay: Stanley Greenberg

Map: Stanley Greenberg and Larry Buchanan

Editing: Kris Graves/Kris Graves Projects 2024

Publisher: Kris Graves Projects

Design: Caleb Cain Marcus/Luminosity Lab

Printing: ABC Tipografia Firenze (Italy)

Hardback with Exposed Glued Text Block (Swiss) binding; 12.5 X 8”; 128 pages; 362 plates; 18 x 24″ double-sided offset map; ISBN 978-1-954877-19-1

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment