Review by Brian Arnold ·

The earth

Is made of earth

And I like that stuff

Adrian Mitchell, “Stufferation”

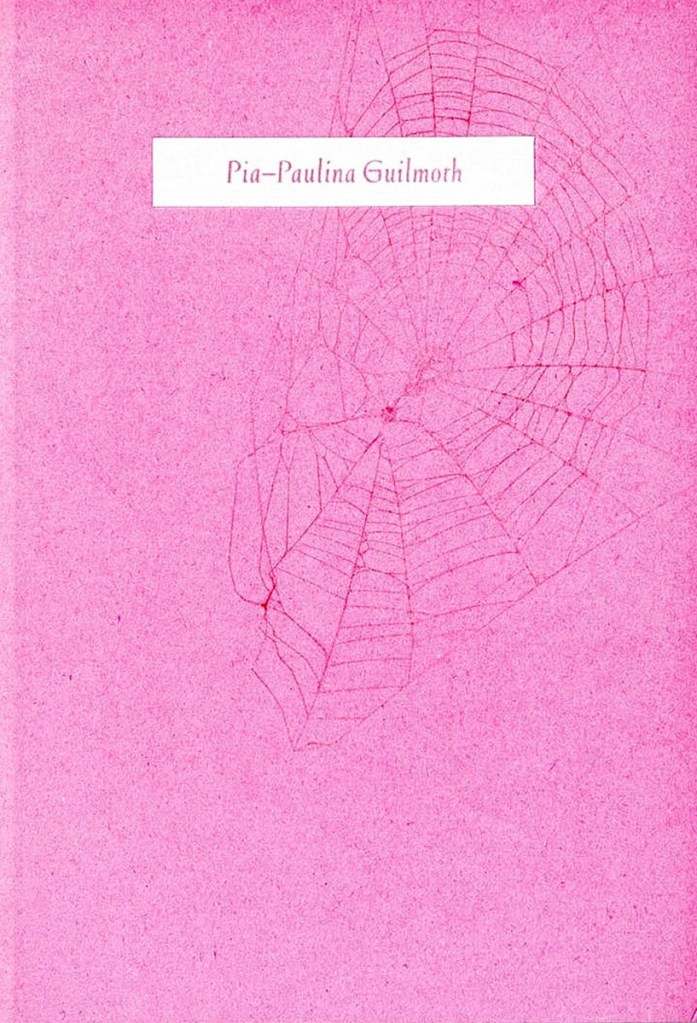

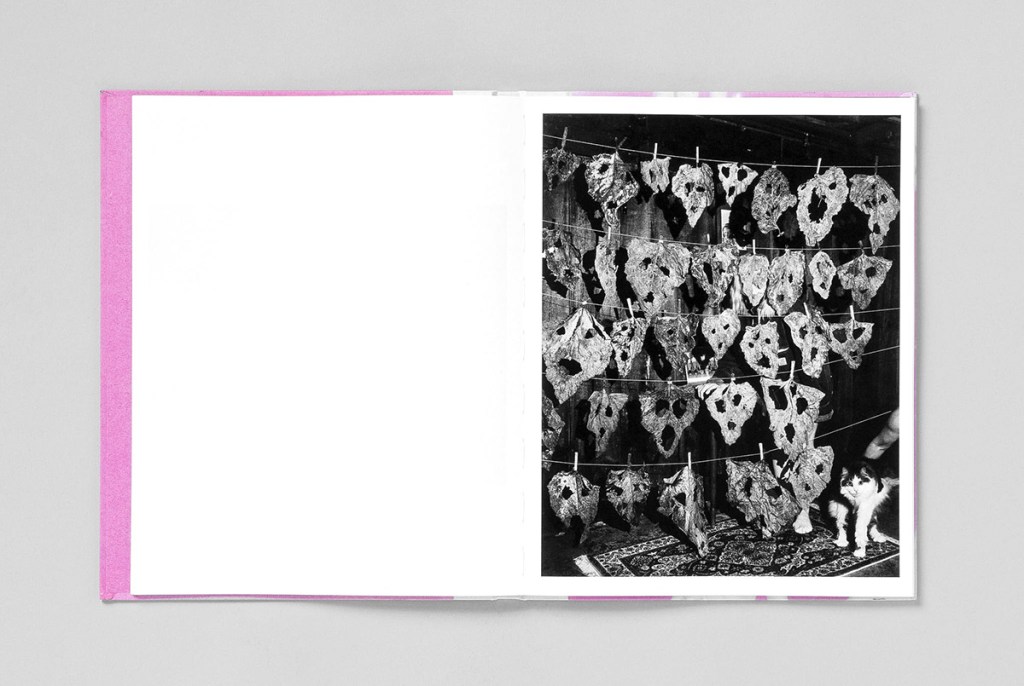

It’s hard to fully describe the complexity that abounds in flowers drink the river, a book of photographs by Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, published by Stanley/Barker and designed by Ramel-Luzoir. It is a rich and compelling story about personal identity, mythology, and the mucky flesh of earth. The pictures are mysterious – with velvety blacks and wonderful monochrome technique – representing personal allegories and metaphors, an unlikely narrative built in the woods of Maine long after dark. To best explain my experience with flowers drink the river, I want to describe the first pictures encountered before getting to the title page; these alone can tell us so much about Guilmoth’s work.

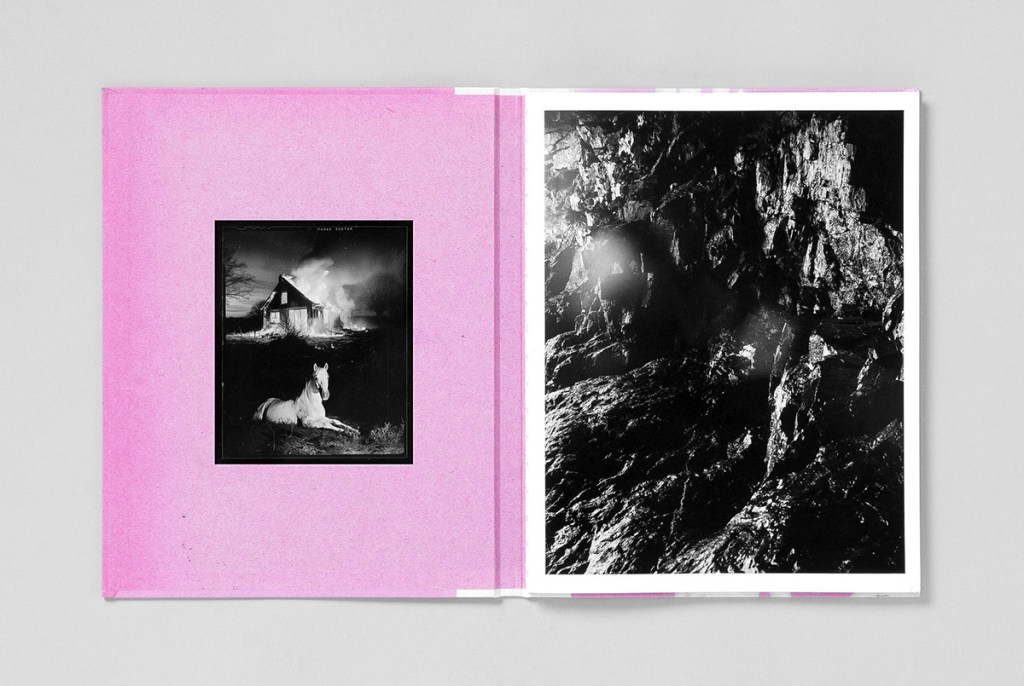

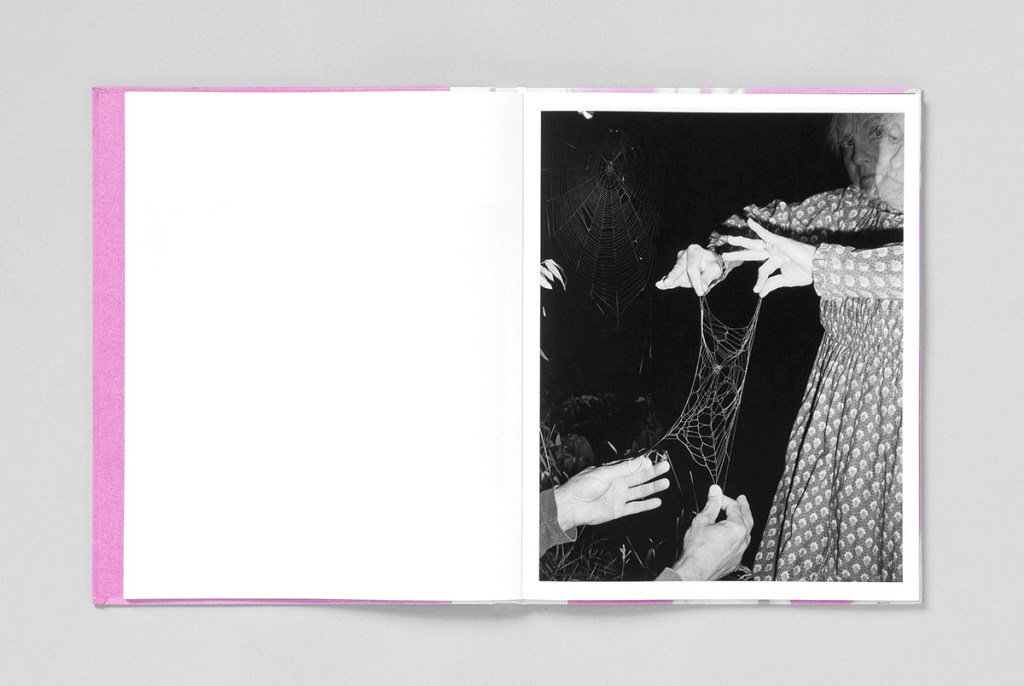

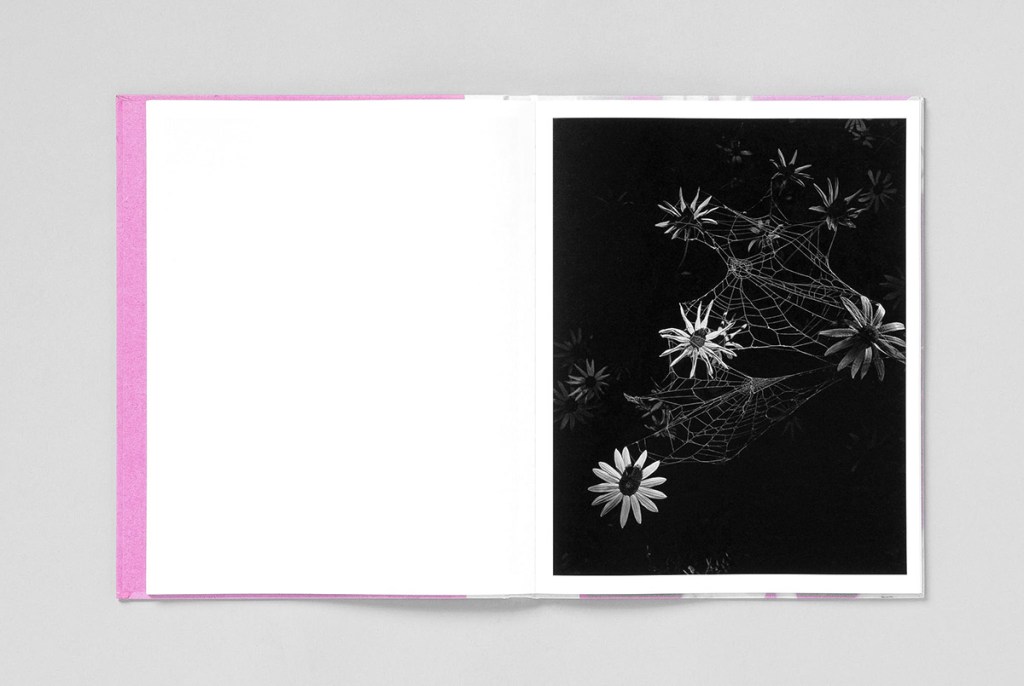

The cover is bound in a dappled pink paper; looking closely you can see how different individual fibers in its surface accepted the dye. The printing on the front is very minimal, a blood red line drawing of a spiderweb derived from one of Guilmoth’s pictures, a linen strip printed with the author’s name is mounted just above its heart. The back cover offers a fuller photographic representation, again of a spiderweb, though this one held together by 3-sets of hands, each adorned with glittery nail-polish. There are a couple of daisies caught in the web, and the hands pull it tight causing the fibers to glow with starry constellations. The inside of the cover has one black-and-white photo pasted in the middle, a 4×5 contact print of a white horse laying in a field, its head cocked toward the camera. Behind it, a fire rages, reducing a house to ashes.

I want to slow down and really unpack this photograph, one in broad circulation that has come to define this work. As rich and telling as the picture looks, there is still more to it than meets the eye. The picture is printed with the make and notch code of the film evident, providing the raw feel of a work print, mounted on the dappled pink paper. The burning house reminds me of a stencil frequently used by artist David Wojnarowicz – first seen in his graffiti but also finding its way into his canvases and prints – as a symbol for the failure of the bourgeoisie, the failure of the American Dream. It’s widely understood that Wojnarowicz used this to symbolize a disillusioned middle-class, of suburban marriages that failed because Daddy likes men (an outspoken advocate for queer civil rights, Wojnarowicz spent his late teens working as a hustler).

The horse in the foreground, still in repose, looks strong and ready but unphased by the fire that rages behind him. Like the burning house, I think the horse is best understood symbolically. In Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, author Tom Robbins uses horses as an important symbol for understanding feminine power (as least as encountered on a lesbian dude ranch in western Oregon), calling them fleshy, organic vibrators that reduce the need for men. The first idea I had about the horse, however, was Lady Godiva, another and more compelling depiction of a horse illustrating the feminine. As a political protest and act of solidarity with the working class, Godiva rode naked through the center of Coventry, a town administered by her husband, openly sharing her sexuality and vulnerability for the greater good. By claiming her feminine power, she also disempowers the residing patriarch.

The first pictures beyond the cover are just as dense and telling. Both are printed much larger than the horse, each framed with a thin white border of paper. The first of these photographs shows a harsh, rocky cave. The rock looks a little menacing, like the wrong step might result in bloody knees. The camera appears as though ascending, like we are returning from the bowels of the earth (there is a hint of sunshine, appearing just out of reach, on the top left of the picture). Flip the page, and the photograph depicts the cosmos, a starry sky that looks warm and infinite, the stuff of dreams. Beautifully rendered in the pictures, the harsh rock and brilliant cosmos feel one and the same, suggesting that what is jagged and painful can also look soothing and brilliant.

To better understand these two pictures, I want to again think by association, this time by looking at Plato’s timeless allegory of the cave, a story at the core of the Greek philosopher’s work. Plato likened our existence to prisoners held captive in a cave, bound in such a way as to recognize there is a life beyond our walls, but also in a way that renders us unable to see or fully grasp what’s behind it all. If one can see outside the cave, however, there is suddenly a possibility for a deeper understanding of our reality.

I mentioned the designers, Ramel-Luzoir, because the book is a stunning object. The pink-paper binding, the rich pacing and sequencing of the pictures, and the beautiful printing all provide a thoughtful translation of Guilmoth’s work and intentions. There is no text in flowers drink the river, so I consulted the Stanley/Barker website to try and get a better understanding of the background behind the pictures. I found important information about Guilmoth that helps explain why I evoke Wojnarowicz, Godiva, and Plato:

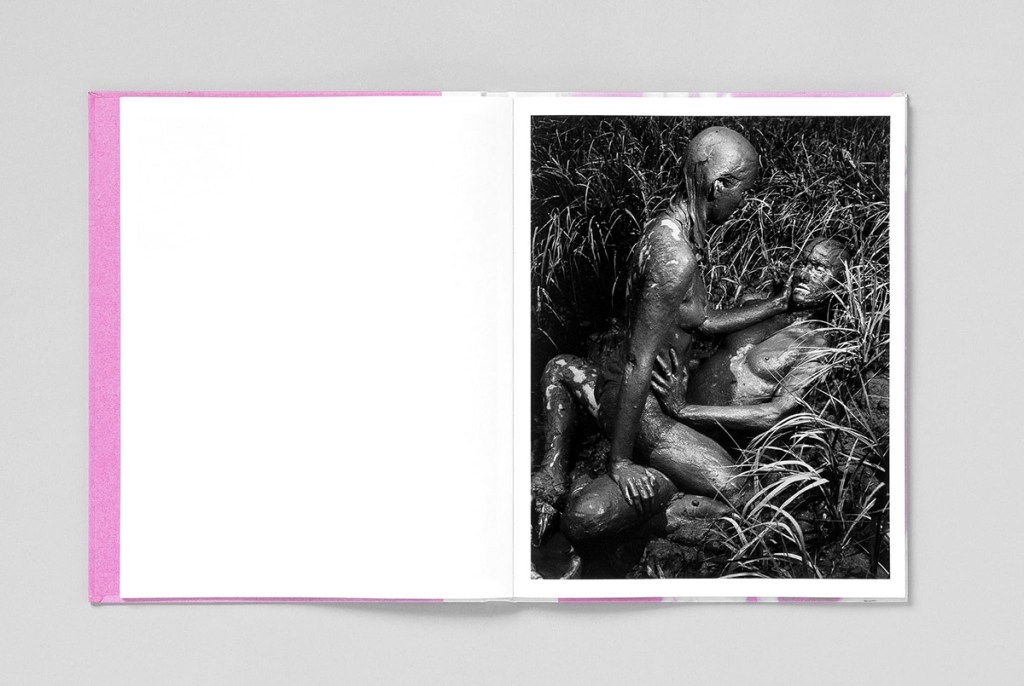

Flowers Drink the River spans the first two years of Pia’s gender transition, as she photographs her small community in rural Maine, and the beauty and terror of living as a trans woman in a small right-wing town. Scenes of moths and floating spider silk, mud-drenched bodies intertwining, a burning house, girlfriends pissing on each other from tree branches, nocturnal animals, and euphoric rituals adorn flash-soaked landscapes… [It] is an animistic search for beauty, resistance, safety, and magic in a world often devoid of these things. It’s a love note to rural working-class people, trans women, lesbians, queer people and the backwoods of central Maine. Pia finds beauty and belonging as she creates a utopia hidden just barely out of reach.

These pictures I described set the tone for the entire book, each page printed with photos full of profound questions and allegories used to describe Guilmoth’s life. The book concludes exactly as it opens, showing the final ascent out of the cave adjacent another view of the cosmos. The picture of the cave is significantly different because this time it does lead us out of darkness – a rocky, wet view leading up to its mouth, bathed in a misty, mystical light.

Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

____________

Pia-Pauline Guilmoth – flowers drink the river

Photographer – Pia-Pauline Guilmoth

Language – English

Publisher – Stanley Barker

Designer – Raeml-Luzoir

Hardback; Swiss bound with facsimmile contact print and fabric tip-in on cover; 80 pages; 12 x 9.5 inches (31 x 24 cm); printed by MAS Matbaa, Instanbul; ISBN 978-1-913288-76-1

Citation: David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night. David Breslin and David Kiehl (editors) Whitney Musuem of American Art/Yale University Press, 2018

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment