Copyright Aperture, 1973

From time to time, I will be digging deep in my photobook library to retrieve photobooks that I think may be relevant. The caveat to this statement is that the photobook is relevant for what ever reasons I choose. In this case, I am reading and preparing a review of the J. Paul Getty Museum 2010 publication, The Photographs of Frederick H. Evans, and I felt that my thoughts about the earlier Aperture photobook might be a nice starting point.

In 1973 Aperture published its retrospective monograph, Frederick H. Evans. Beaumont Newhall (b 1908, d 1993) was the editor and provided the introductory essay to this photobook. Newhall trivia; MOMA’s first director of photography in 1940, then curator of the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House 1948-1958, subsequently it’s Director from 1958 to 1971.

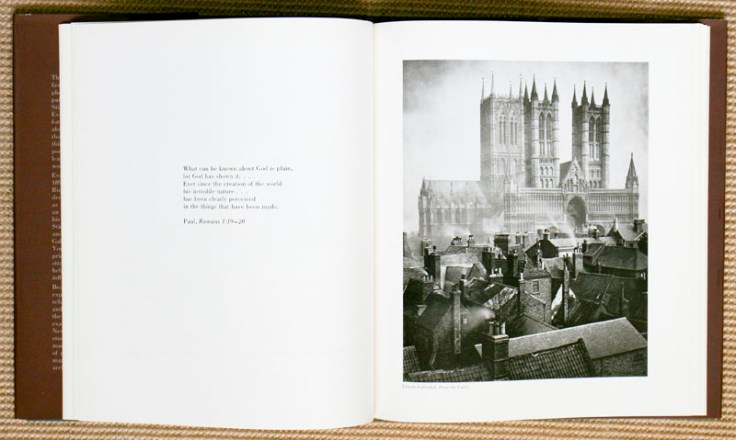

Evans was an English photographer (b. 1853, d. 1943, England) probably best known for his interpretative photographs of English and French Cathedrals. He was equally proficient photographing individuals and urban landscapes, creating well known portraits of F. Holland Day, Alvin Coburn, George Bernard Shaw (also an ardent support of Evans photographs) and Aubrey Beardsley.

A historical trivia is that Alfred Stieglitz at the turn of the century was a fan and supporter of Evan’s cathedral photographs, and both were members of the London based Linked Ring. Evans photographs and writings were published in Steiglitz’s Camera Work, starting with edition number 4 in 1904, and Evans exhibited at Steiglitz’s “291” gallery in 1906 at New York.

Interesting technical photographic trivia; Evans advocated a “straight” photographic techniques and his style laid the foundation for the practice of pre-visualization and the concepts behind the zone system. He would spend two weeks in a cathedral, studying and takes notes on the location of light, intensity of the light and potential location of the camera and with which lens set to achieve the final print he was seeking. If the lighting was not right, he would determine which time of year to return to achieve the effect he anticipated.

Evans had developed a two layer emulsion negative (double-coated plate) that with one extended exposure would capture the full range of light. The resulting negative was then coupled with a long tonal range platinum contact printing paper. He could capture detail in the shadows of the cathedral interiors without blowing out the details of the stained glass windows. In today terms, that is a true HDR situation, or at least shooting in RAW and using ALL of the Photoshop tricks to save the exposure.

Likewise, with the view camera lens of his time, with one set of lens components, you could create a wide variety of optical effects. His single seven piece lens set was probably the equivalent of our zoom lens today.

Evans was a strong advocate of the straight photograph (unaltered negative and photographic print) versus the then prevalent photographic altering practices of the “fine art” Pictorialist, such as scratching the negative or use of gum printing to create an “artistic” effect. He advocated exposures with the aperture at f/32 to capture details and great depths of field. He published an article requiring photographers to get the negative correct, everything else will follow. All of these three decades before Ansel Adams started to codified similar opinions for the f/32 group and the subsequent West Coast (USA) style of straight photography.

There is a timelessness of his cathedral photographs that remind me of Eugene Atget. Evans chose to photograph at specific times of day to minimize mankind’s presence, and capture a certain kind of illuminating light. Evans perhaps was more interested than Atget in creating an aesthetic object, the fine art photographic print. A second point of departure is that Evans seems to have been more interested in the interiors than the exteriors, but nevertheless, I found many of Evans cathedral external landscape photographs that attempt to contextualize the place to be very Atget like.

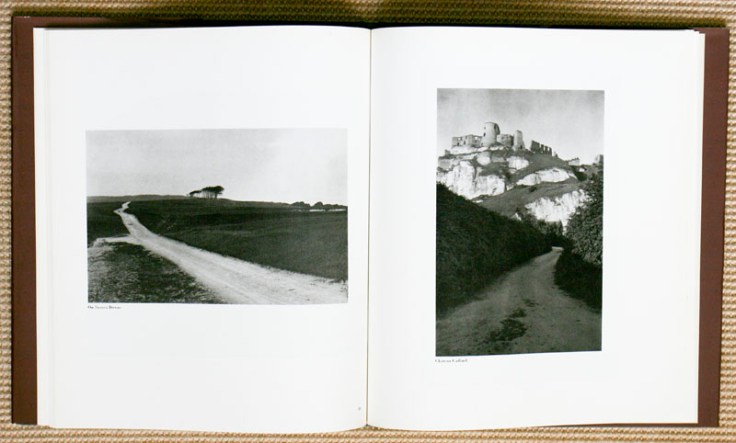

Evans strived for an aesthetic interpretation of his subjects, which was to be imbued with a sense of poetry and wonder. What probably differentiated him from others was his sensitivity to the effects of light and how that might effect his eventual composition. Even in the early 1900’s, it was remarked that many photographers were searching his tripod marks in order to create their photographs, but although they may have emulated his composition, they still did not seem to grasp the nuances of capturing the light. He was looking for aesthetic beauty, a balance of forms, shapes, textures and tonality, which would be peaceful for prolonged contemplation. Perhaps similar to the West Coast photographic style about aesthetic landscape photography still in vogue today, such as John Sexton, Clyde Butcher, Michael Levin, Michael Kenna and Josef Hoflehner

It does not take long when walking through one of old cathedrals in Europe to realize that they tend to be overly monochromatically gray. The same gray tonality of gray column adjacent to gray stone can lead to a very flat photograph. The use of sunlight to differential the levels and planes of the various surfaces could make a huge difference in reading the interior spaces, which became Evans expertise. He was also able to overcome the deep and dark shadows, from personal observation, brilliant shafts of sunlight, usually through jewel like stained glass windows, either perched high above or massive walls of colored matrix.

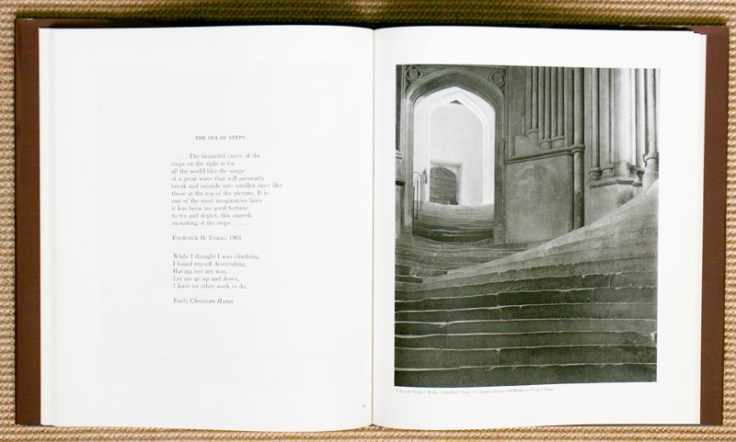

In Evans time, photographs that included paths, open windows, open doors and doorways, and stairs were understood as visual tools to “lead the eye” and “pull the viewer forward”. These motifs and similar compositions now imply more metaphoric themes of time, personal journeys, memory, and history.

“Sea of Steps”, is probably one of his better known photographs of Wells Cathedral, below, and one that took a number of successive trips and studies over a series of year to final achieve what he was striving for. Evans had seen the wear on the steps when caught with the right light, as a wave of steps undulating upward to the far door. A rim light on the edge of each step emphasized the heavy uneven wear of each step, providing a ripple like appearance that appeared to move upward. It was an effective visual framing that he continued to use on other subjects, especially if stairs or steps were included.

Even though a staunch advocate of the straight print, he would create and print a softer focus or incorporate atmospheric haze in a photograph to gain a purposeful poetic and interpretative effect. It was necessary for Evans to convey an emotional quality in his photographs. His use of atmospheric haze also creates a three dimensional illusion, of depth and space within a two dimensional medium. Evans claimed that his photographs were inspired by the atmospheric and poetic painting of J.M.W. Turner. In his day, to create a topology photograph was considered an insult.

The hardcover book was published with a dust cover, although obvious in the cover image above, mine has a slight tear the in the dust cover and not so obvious, the end panel of the dust cover has been sun-faded over the years. The page stock is matte and the images are unvarnished, thus a subdued luminance. The printing color of each black and white image is a consistent natural gray.

Publishing trivia, shortly after purchasing the book, I became aware the final editing of this book did not go as well as Aperture had planned, as eight plates were mis-captioned. I did not keep the notification letter, but I did pencil the corrections in my copy. So there will probably be some confusion if some unaware person attempts to references the interior photographs based on the printed captions in this book.

Unlike the recent J Paul Getty Museum photobook on Evans, the captions in the Aperture book do not reference the photographs date of origin.

by Douglas Stockdale

great