Review and Interview by Hans Hickerson ·

Publishers of photobooks publish photography books, but sometimes they also publish books about photography books. Jason Eskenazi’s The Americans List, published by Red Hook Editions, is a good example. It is about Robert Frank’s seminal book The Americans. Eskenazi asked photographers he knew and met, as well as some he searched out, to choose their favorite photograph from the book and write something about it.

This is the third and final edition of the book. The first, published in 2012, had 276 responses, the second from 2016 included additional responses totaling 368, and the current edition includes all responses to date and has 538. That is a lot of people weighing in to give their opinion, and the results are fascinating. Some of the photographs are quite popular, for example “Trolley – New Orleans” with 40 listings, while others, such as “Casino – Elko, Nevada” or “Bar – Detroit,” have none. Care was taken to reproduce the original fonts and languages of the responses and it gives the texts a feeling of variety and authenticity.

The Americans List is not a book that you are likely to read through cover to cover. You are more likely to thumb through it, looking for names or photos you recognize, picking it up again as a reference. Or you might read an entry or two every evening before bed. It is an especially rich reference – a monument to a monument. It is a wonderful example of listening, of encouraging an exchange of views, of fostering community among photographers, and of starting an open-ended discussion – or rather 538 discussions. A simple but brilliant idea.

Because there are no photographs to decipher, no visual analysis necessary, instead I talked to Eskenazi about the book, his own work, and Red Hook Editions. Below is our conversation, edited for clarity.

HH: Tell us about when Red Hook Editions started. It is presented as “a publishing community.” Who was involved?

JE: Red Hook Editions started as a kind of community publisher. We call ourselves a publishing community still, even though I am the only person in Red Hook Editions. But I feel like the photographers that I publish are part of a community. Yes, it has changed over the years, after COVID, and I think people are staying home more, they got used to being more on their own. But there is still a community, especially in New York. There’s always been a community. I’ve known some people 25 years – photographers in New York.

HH: Did you start it? You and some others initially?

JE: I started it as “doing business as” – DBA – Red Hook Editions – to publish Wonderland, or to re-print Wonderland it must have been. And then, because I lived in Red Hook with other photographers, we decided to make it a company and invite other people to make books. It has gone through many iterations, but I have always been in it, and part owner of it, and now I am the only owner of it, and it seems like it’s going to go into the future like that.

HH: What year did you start?

JE: I think it was 2009. I was working at the Met in 2009 and I re-printed Wonderland while I was working there. We might have incorporated as a business in 2012. We’re an LLC.

HH: You don’t have to have a day job?

JE: I don’t make money from Red Hook Editions. It works like a non-profit. I make money selling my books through Red Hook Editions as the other authors do as well. My books still sell. Every day there are books selling. I’ll run out of some of them soon. Like Wonderland is basically finished at the end of the year.

It makes a little profit, but that profit goes into, like, going to Paris, for Paris Photo for Polycopies and paying 800 Euros for a table, and then flying there, paying for food and an apartment. The money basically goes back into the company, and for me it has always been like a platform. So I’m happy to share my platform with others, almost like a photo agency, but instead of selling Ektachromes, we’re selling books. And the photographers get the lion’s share of the profits. They invest in the book. We have an upside-down model. The photographers pay for the books, but then they get the bigger part of the profits. Red Hook Editions takes a small percentage to cover expenses. To store the books, for example – we have thousands of books – we’ve got to store them somewhere, and my garage is not that big. It’s all about sustaining and I don’t get a paycheck.

HH: I don’t think anybody does. Of maybe some people somewhere do. Someone pointed out this Reddit thread to me recently about the fact that even bigger, established photobook publishers expect the author to fork out a substantial sum up front to get their book published.

JE: It’s been (like that) from the eighties or nineties. Aperture was maybe the first, and they asked for the photographer to raise fifty percent. You didn’t pay only if you were lucky enough to get published by Random House or Steidl – Steidl I guess still pays for the books. But yes, most publishers have some kind of deal where they make you pay for it, and the photographer doesn’t get anything. They get twenty books, and then they say adios, go be happy with your twenty books, and have a published book, which a lot of photographers think, well that’s the best deal I am going to get. I want my book out there.

We always thought that we were pro-photographer. So the photographer makes the money, but then unfortunately I don’t make any money, but I don’t know, it’s like community. I still believe in the photo community in some ways. You know, Dog Food was all about photo-community, and The Americans List is all about photo community. I’m still doing that. But again, I benefit by publishing my own books and having my books next to other books that I like.

And I’m sure you’ll ask this question: I basically choose the books, and I choose them like, OMG, that’s a great book, I have to do it. It’s going to look great next to mine or some other ones. It’s got to be done. If I do not feel like amazingly passionate about it, I cannot take on a book because it’s like having a child. I have to lug those books all around the world. I don’t want to stand behind a table of books that I don’t totally believe in. Just like sequencing and editing, I feel like I’m also sequencing and editing the line of books, like there’s a thread that goes throughout the Red Hook Editions books, whether it’s stylistically, subject matter, and I feel like I’m curating a publishing company.

HH: It seems like you are at a good place. From what I see, it seems that some of these younger, newer publishers that are now at all the fairs – Polycopies, LA, New York – it looks to me like at this point it’s a business and they need to keep creating product to pay themselves and I don’t see them at that creative point where they can choose whatever they want, when they want and do new things with it. They have to keep producing safe stuff that they can sell and fill the bookshelves with.

JE: The ones I know are passionate about what they do and the books they choose, but I don’t know their model and if they make any money at it. Some of them go to every single fair imaginable – LA, Tokyo, Brussels – it’s a full-time job and they sell other things like T-shirts. I’m not a full-time publisher. I’m a photographer. I’m still shooting, and making books. I still have a wanderlust to go, and actually I live in Istanbul, officially, so I’m here taking care of my mother most of the time when I’m in New York, but I’m going back to Istanbul over the winter, and I’m going to Syria again, maybe Ukraine. I’m still working it.

HH: Do you just get assignments or you just take the pictures?

No, no assignments. When I did live in Moscow in the 90s I did get assignments back then because that was what you did as a photo-journalist and when the agencies were more active and when there was work, for the New York Times, the magazine, Time magazine. I worked a lot for the Open Society Institute. I did those things, but I never enjoyed it. I always shot on the side my own work. And then I gravitated toward getting grants – a Guggenheim in 1999, a Dorothea Lange in 1999, a Fulbright in 2004. I’d make some money from my books, a few thousand dollars, and go away and buy a hundred rolls of Tri-X and I’d live in Istanbul and I’d travel and take pictures and come back when I have no money, and I’d do it all over again. I never changed, and it’s funny, I’m developing film now, a hundred rolls, and I’m still using the same room in my mother’s house, which is absolutely not a professional place to do film. I’ve been developing film in this room for forty years.

HH: Do you scan the negatives? You don’t print everything?

No, I used to make work prints, but basically for books after seeing the images I scan them for books.

HH: That’s what I’m doing. I shot so much in the 80s and 90s that I have piles of notebooks with negatives. You never have time to actually print them. I printed some. But then you can go back and see what you were actually doing, so now I’m making books. I have submitted to some places and gotten some nibbles, but it’s so laborious, I mean I’ll be dead by the time someone wants to do one of my books. I’m retired and in the meantime I can finance making a limited quantity. I’m trying to break into the photo-market circuit, but you’re locked out of the bigger events. People that started earlier are like the inside group and more established, and so there’s just no room at events.

JE: This is the first year that Red Hook Editions has gotten into the New York Art Book Fair. We tried for many years. This is the first year that we actually got in.

HH: As far as the book, The Americans List, I was wondering about the evolution. You got the idea talking to Robert Frank and then…

JE: No, I was working at the Met for over a year already and the Robert Frank Looking In show came to the Met. I had never met Robert Frank but I had seen him around walking around the Bowery but I never said anything to him. I was working at the Met and guarding the Robert Frank show, and the other guards knew I was a photographer so they actually let me stay in those rooms the entire day. If you know how the Met works, you have to get moved. I can’t give away their security secrets, but they allowed me to stay there. I was watching, seeing all my friends come into the show and other photographers that I knew, and it sparked when Joel Meyerowitz came in. I had met him or knew him and I asked him his favorite image. He said something, and then other people came in, and I started to gather the information that way.

And this show actually got me back out on the road, because in those years I was really poor. I got the job at the Met basically to get the health insurance. That job of guarding the show catapulted me back into the world to take pictures. I quit because of that show and I went to Cairo and Istanbul and started the work that was later to become Black Gardens. And during those years, 2009 to 2012, I was emailing everyone I had come into contact with about The Americans List and getting them to write something and email it to me. I also used the font from their email in the book. That’s why you see the different fonts in the book. That was a design element, because it was so monotonous.

About the time I quit, I met Robert Frank, at the closing party. I describe it in the book. I put my guard’s uniform in the locker, walked out of the Met from the garage, then came through the front door, with a nice jacket on, a sports jacket, and then I met Robert Frank, and then later that evening we all went downtown at a restaurant on Bleeker across from his house. Then also it took time to go to his house. That eventually happened months or a year later. But at that time I started to travel again, and I was living in Istanbul.

For The Americans List I was definitely going after certain people to get their responses, and it took years and years to get them to write something. That’s the way that evolved. That’s hopefully the last edition. I don’t want to do this again. It’s a lot about community. For me the book is less a kind of fanzine about Robert Frank and more a book that is like an access that everybody knows that everyone can riff off, and it says more about their own photography than about Robert Frank.

A good example is Ralph Gibson (who) gave a great answer. He chose the absolutely most boring photo from The Americans, which is this art house in Salt Lake City. I couldn’t fathom how he would like such a picture, but he said, well, it’s because of the geometry, look at this, look at that. There’s a triangle, there’s a square, there’s a sphere. And then I said, that looks like a Ralph Gibson photo, actually. So you see that they were riffing in that way and saying a lot about how they felt. And then it’s also interesting to see which photographers like the same image, that can be diametrically opposed photography types.

That can be interesting as well, to see who likes the same photo you like. There were like five photos that a lot of people chose, “Elevator Girl,” the last photo with the family, “Canal Street.” And then there are a few photos no one chose. I’ve never counted, but there have to be six or seven photos that no one chose.

HH: I tried to choose one that was less well-known, because it still resonates with me, and it’s interesting because you chose the same one, the men’s restroom. If you live in another country, you do not see – I mean, who is getting their shoes shined, an elegant kind of thing, in a place where people are peeing? It’s just so American. For us to be totally blind to any sort of elegance, or life-style.

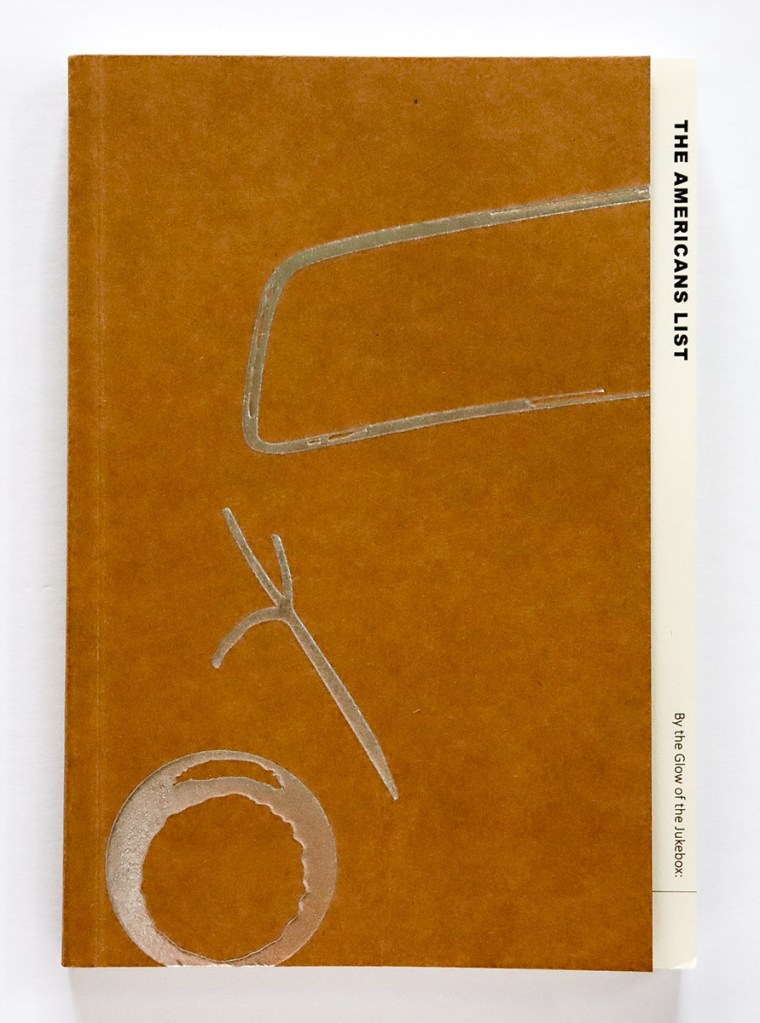

JE: The design of the book is that, after the first edition, I went to the printer, it was being printed in Istanbul, and I saw the book before they cut it, and I said, Wow. For the second edition we’re not cutting the book. That’s how you have this kind of lip on the right side, and you have the printer’s marks inside as well – that’s before the book gets cut. For me it flaps open better, like a bible. I basically designed the book like that for the second edition, and for the third edition I came up with a silver-foil cover idea, and also restructuring the book according to image, and that was also in the works ten years ago. It was tedious. Alex did a lot of amazing, tedious work aligning the text and adding more and it was quite a job to do something like that.

HH: I haven’t started to read it because it’s not the kind of thing you can just pick up and read. It’s something you have on your shelf and look things up. But I think it’s also brilliant because, okay, how do you sell a book like this? Well there are five hundred something people who probably want a copy of it because they’re in it. That’s super smart – participation. And it’s a dialogue. People are conversing. It’s not a gimmick. Maybe professors will order it for a class. For a photography class,

JE: That’s what I’m hoping. Teachers can’t make the students buy something, so I guess they can put it in the library. It’s not like a university where you have to buy the geometry book or something. I’ve also offered it many times to teachers at deep discounts if they wanted to buy ten or twelve for their class.

For me it’s a great education tool. Maybe one of the best. Having a dialogue with all these photographers. Unedited in some ways. We left their responses as they said it, with all the mistakes and stuff like that. It’s also a great read on an airplane if you want to take a nap.

HH: It’s a resource. And the more photographers you know, the more interesting it is. There are so many people in there. I have no clue who they are. Or let alone their style.

JE: I wanted to be democratic. I didn’t just want the heavy hitters. The criteria was, anyone who walks around with a camera, beating the streets, is eligible to write something. They’re all photographers. Maybe one or two other people slipped in. Curators slipped in, because they were important, someone like Stuart Alexander who knows Robert Frank forwards and backwards. I don’t think he’s necessarily a photographer. He was important to put in there. And people like that, some curators like Sarah Greenough who was the one who built that show, from the Washington, D.C. gallery. She’s in there, Phil Bookman and other people like that. Mary Frank is in there, you know, Robert’s first wife. She’s a painter, but she was important. June Leaf is in there. She’s not a photographer.

So, yes, it was, let’s say, a slog, to use that word, to do it. It took a lot of emailing photographers for years and years and years. Of course, people put it on their back burner to write something. But I got a lot of people to do it. Some people I didn’t get, like Nan Goldin I really wanted, even Annie Liebovitz, to write something. Other people like that I couldn’t get. But I got who I can get.

HH: Is there anything else you’d like to mention?

I think I mention this in the book as well, that one of the greatest moments is I did go over to Robert Frank’s house. I think it was a summer day. Usually, I would go there with someone else, to give me a buffer. Like what do I say to Robert Frank? So I did go over once alone. I was sitting in his kitchen. June, his wife, was there, and she said I’m going out for ice cream. And then I was left alone with Robert Frank. And I said, wow, what am I going to do? Ask some stupid questions? The second edition of The Americans List was there on the table, and I said to Robert, do you want me to read from the book? And he goes OK. And I started to read the descriptions of the photos, and he would try to conjure up the actual image that they were talking about. And you could see a light bulb go off and he would say, ah yes, San Francisco. This for me was like the moment in my life that I was like talking to Picasso. I was reading the fairy tale to the fairy tale maker. And for me this was a great moment. That was a special moment I had with him.

And also, Mary Frank. I got her very late. I thought to myself, who is never going to answer the question – Mary Frank is never going to answer. But I wrote to her. She lives in Woodstock. I might have spoken to her on the phone. She says, okay I’ll do it. And she chose the last image in the book, of course, because she’s in the car with her children, Pablo and Andrea. And the tragedy that happened to both of them. And she wrote something that nobody else would ever know. She wrote, it was freezing cold in Texas and I had to warm up some milk for the kids and we couldn’t find anything and we warmed it up in a Coke bottle. This kind of thing that only she would know, this personal experience. And she said at the end, Robert had no sense of direction whatsoever. And to think who is Robert Frank, driving around the country, sometimes alone, sometimes with others, that he would have no sense of direction. Strange.

For me the last edition of the book (the third) becomes more personal. Before it was more like an exercise. Almost like a thesis. A college term paper, of getting people to write something. And then it became very personal for me, and that’s how I can just say, that’s it. I’m never going to do it again, it’s just too much. But I’m glad I did it. It came about very organically because if I hadn’t worked at the Met, I never would have done such a book on my own. It happened because I was guarding the show. And I was really bored, and I started to ask the question to my friends. That’s how it came about.

And one time Koudelka came in but he always came in the back entrance. And I saw him twice. And I remember saying to the curator, Jeff Rosenheim, who I knew a bit, and I said Jeff, the second most famous living photographer is here. And he goes, Who? And I go, Jeff, you’re the curator of photographs at the Met, and he said, Irving Penn. And I said no. Josef Koudelka. And then the next day, Irving Penn died. So that was like really very strange.

It was only twenty months that I worked at the Met, but it felt like twenty years. I’m happy for that time, but happy I left. I was pushed out the door by The Americans, by Robert Frank. Back out on the road.

Hans Hickerson, Editor of the PhotoBook Journal, is a photographer and photobook artist from Portland, Oregon.

Jason Eskenazi – The Americans List 3rd edition

Editor: Jason Eskenazi (born 1960, lives in Istanbul and New York)

Publisher: Red Hook Editions © 2025

Language: English and other

Texts: multiple contributors

Design: Alexander Paterson-Jones, Jason Eskenazi

Printing: Onikinci Matbaa, Istanbul

Softcover; perfect binding, 262 pages, paginated; 22.5 x 15.5 cm; ISBN 979-0-9841954-5-9

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment