Review by Brian O’Neill ·

Climate change, and various aspects of it, from forest fires, to drought, to adaptive landscaping and technologies, as well as oil extraction, have become more and more common within the world of fine art and documentary photography. Often, photographic projects oriented around climate change take an approach to human stories (relying on environmental portraits, for example) or to landscapes (sometimes featuring animals, especially megafauna). Even the more abstract projects that deal with this subject seem to fall into one or the other mode of presentation, like Magnum photographer Trent Parke’s recent work, Crimson Line, which relies on a unique approach to the landscape genre with his use of telephoto lenses. Other projects that broach this topic can be left wanting due to their lackluster engagement with the politics of climate change. By contrast, Nora Bibel’s 2024 photographic monograph Uncertain Homelands bursts the limits of conventional approaches to making climate change visible.

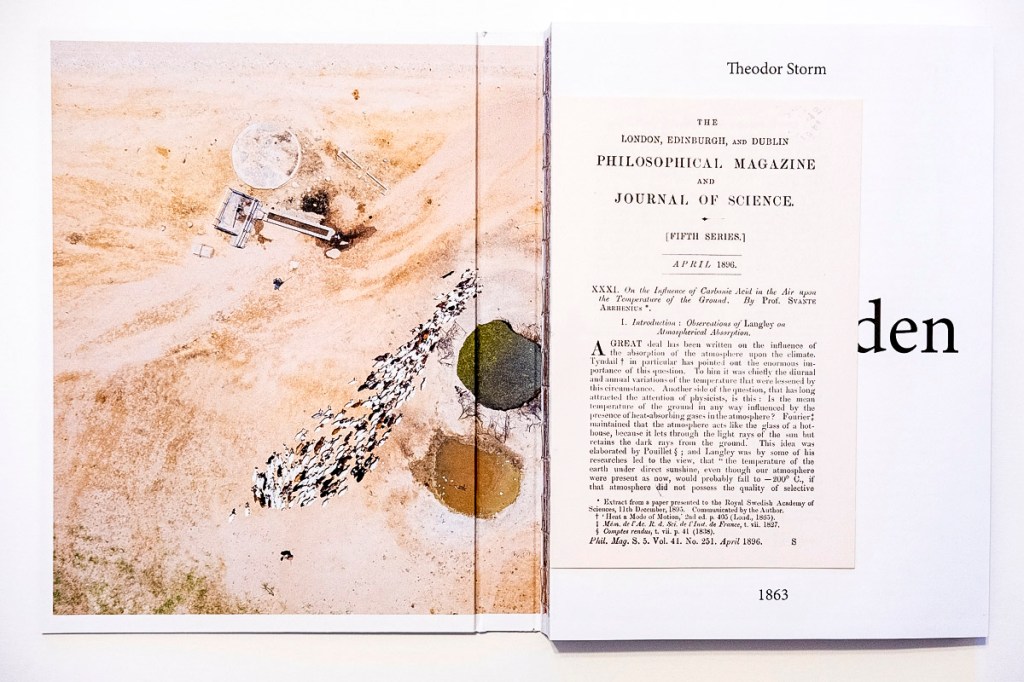

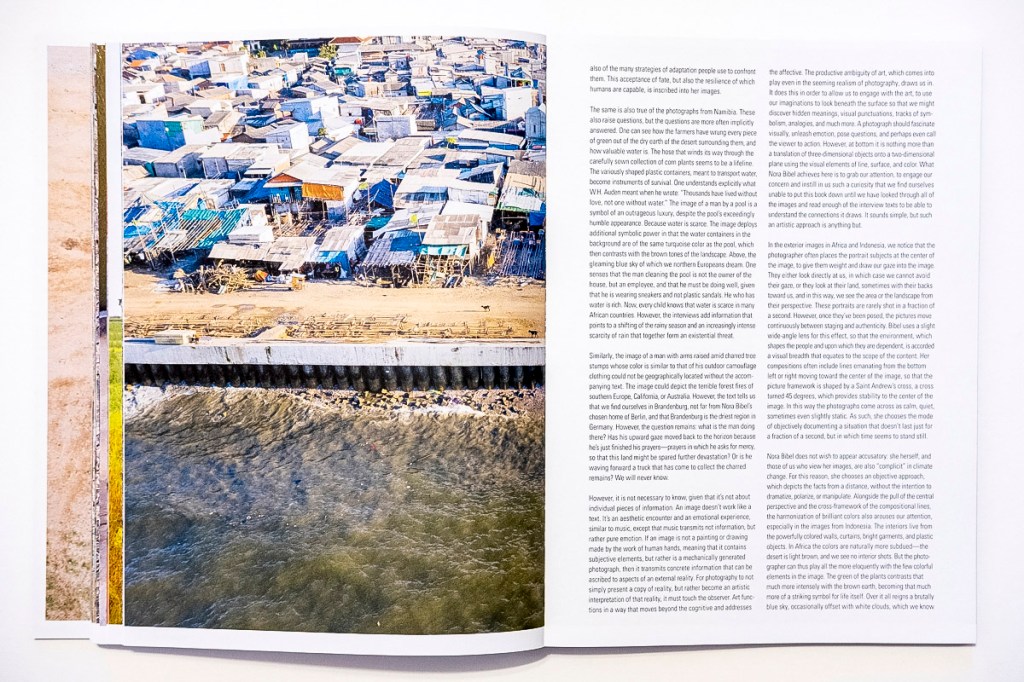

Bibel’s work here is notably rigorous on a number of levels. To begin, the use of a variety of non-photographic, historical resources, like scientific reports dating as far back as 1896, provide a depth of understanding about climate change and the origins of our scientific understanding of the phenomena. Set alongside the images with finely produced newsprint paper, the reader also gets a snippet of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report at the end of the book. These texts help to contextualize the images within but also serve as a useful contrast. Bibel seems to be saying that we need a more comprehension “vision” of the climate crisis, one that ranges from the more abstract scientific discourse to the capturing of lived reality that is possible through photographic practice. The variety of textual references abounds in other ways as well, ranging from a section of text by 19th century German poet and writer Theodor Storm to more academic narrations of landscapes, such as that on the deserts of Namibia by scholar Rosa-Stella Mbulu. An essay by Christiane Stahl towards the end of the book contextualizes the work further, speaking to its merits.

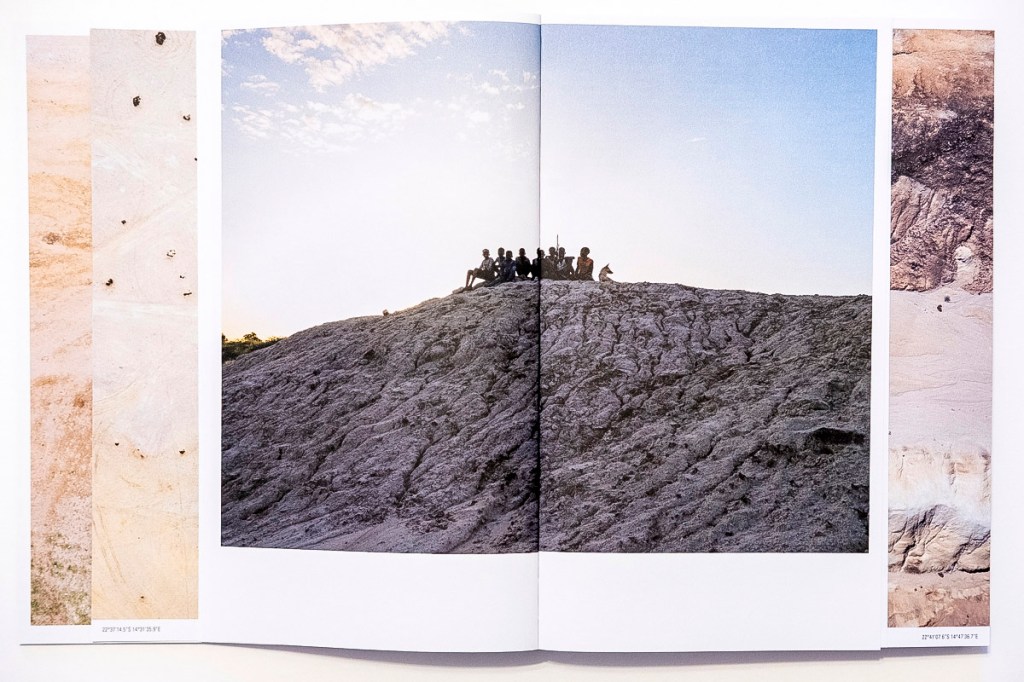

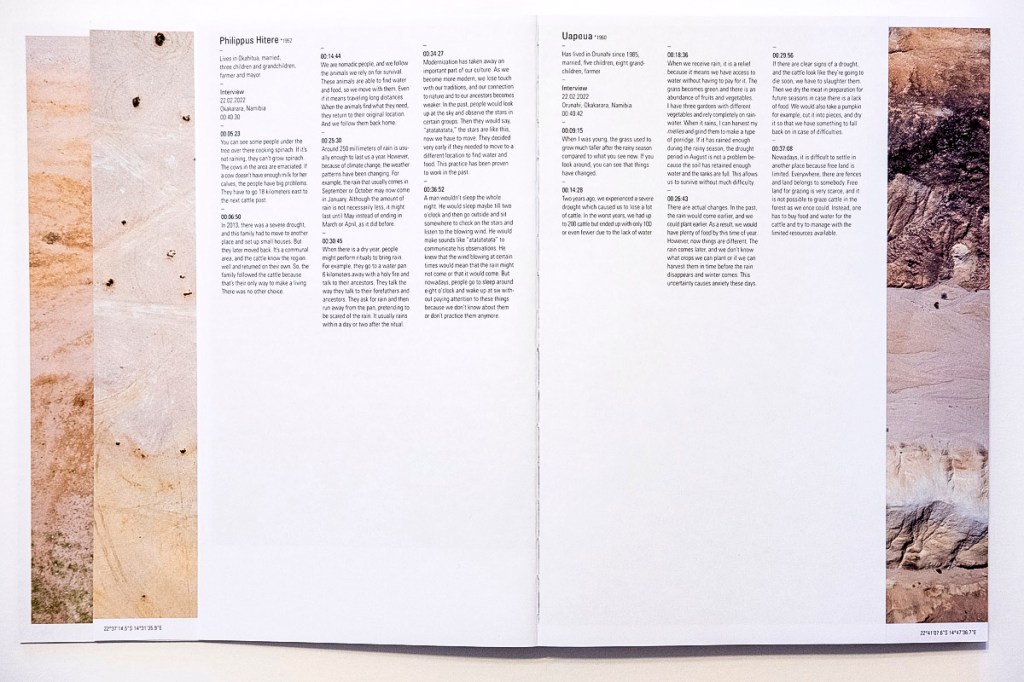

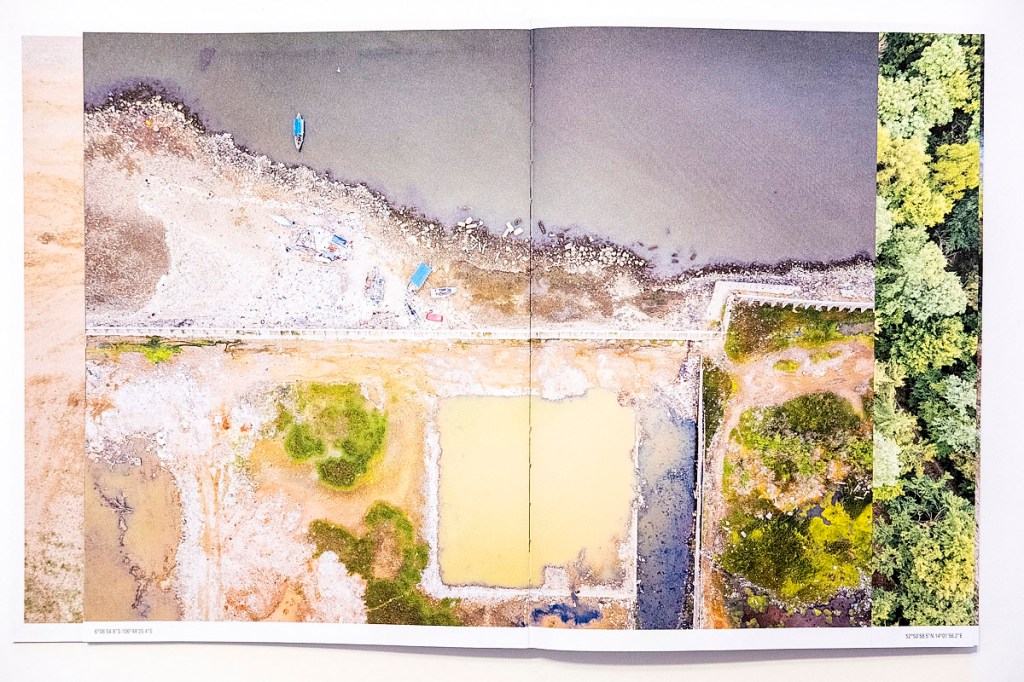

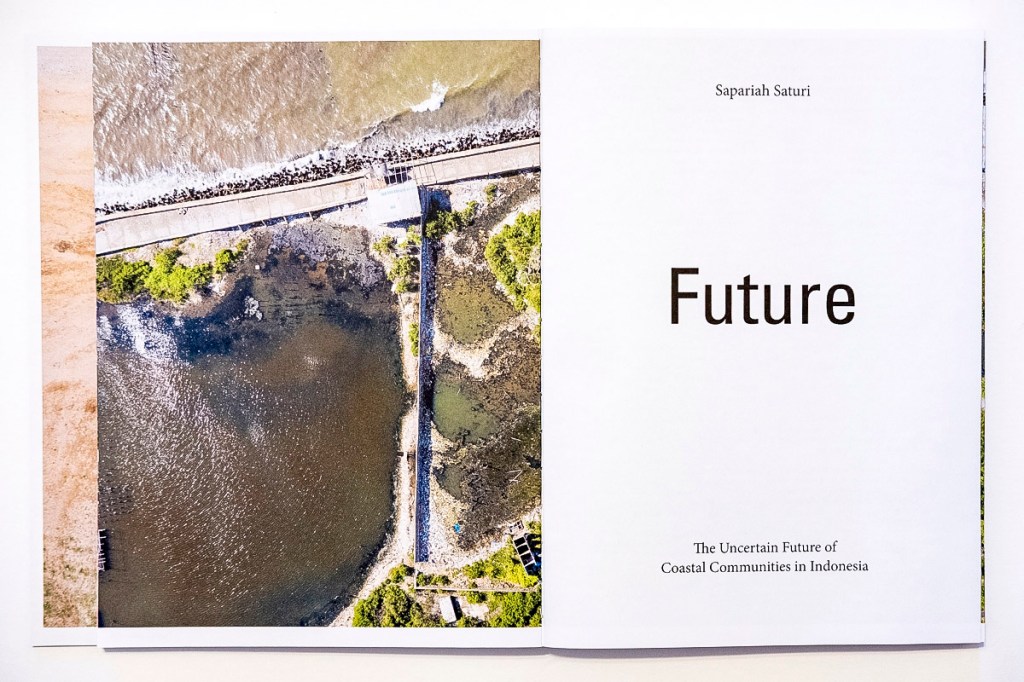

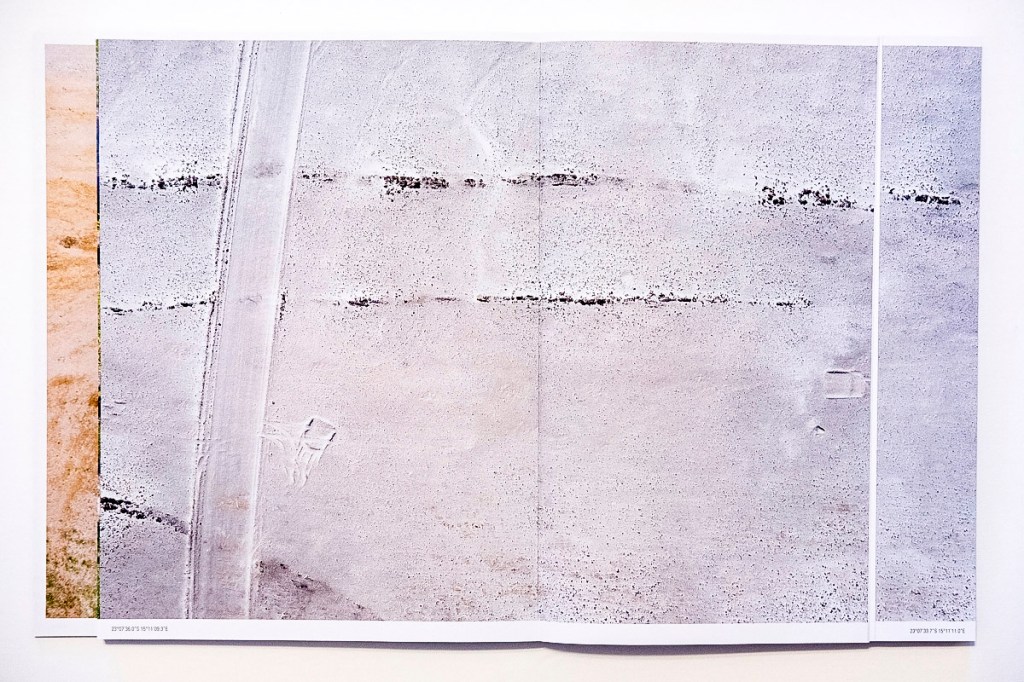

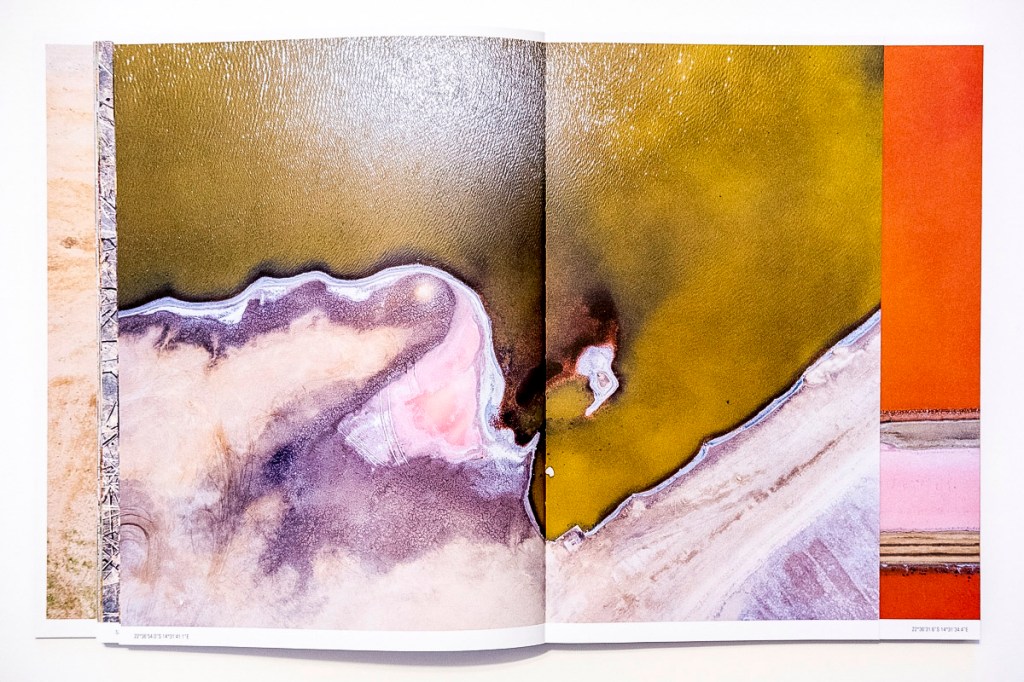

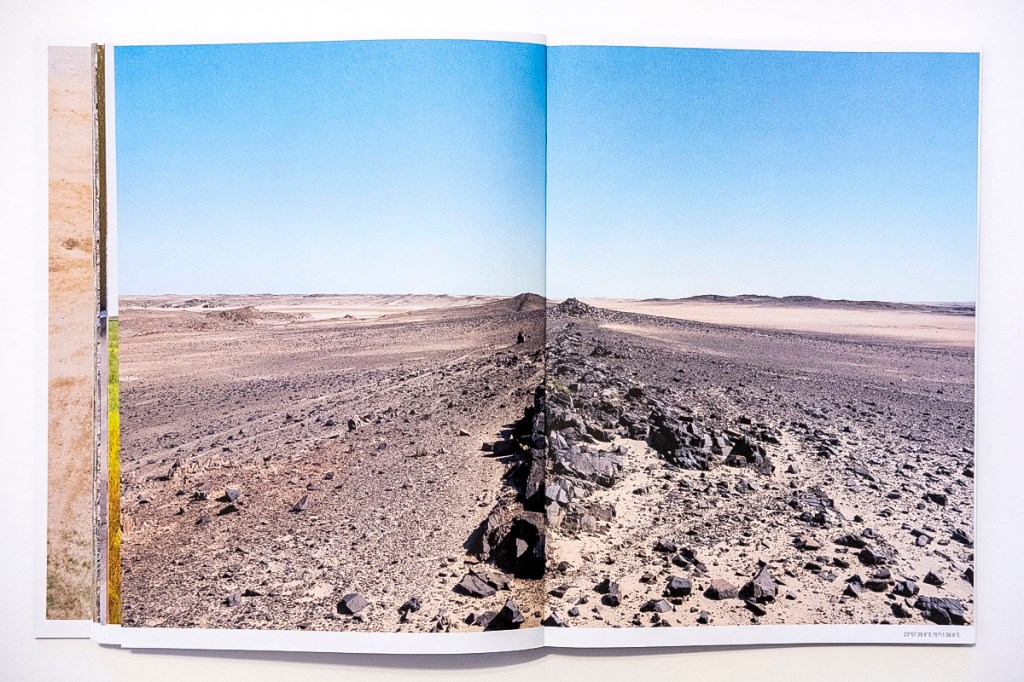

The book is also wide-ranging in terms of geography. It proceeds as an exploration of Indonesia, Namibia, and Germany. In this way, the book relies on the logic of many, especially European research projects that utilize a multi-part case study approach. There is also an element of a cultural survey approach happening here (indeed, Christiane Stahl mentions how the interviews in the book depict “universal” qualities), common to photographic projects of this type, although the reasons for choosing these three “sites” remains a bit opaque. Connections are not really made between the cases beyond the idea that through surveying different nation-states in the world-system, we, the readers, learn about the multifaceted impacts of climate change. This assumes a bit of methodological knowledge on the apt of the reader. For instance, we might imagine that the logic is loosely comparative. Presumably, an underlying idea here is that Germany was chosen as it was a high income, high GDP country, with Indonesia falling more in the middle of these variables, and Namibia the lower end of the spectrum. The colonial connection between Namibia and Germany is not unpacked, although the texts across the book help to loosely illuminate some basic contours of how global inequalities and the unequal exchanges of resources are implied in climate change. And, within the broader remit of climate change, water is a unifying theme. This variously includes the issue of access to water, but also flooding, and the control of water in the form of canals, pools, rivers etc. Throughout, the organization tends towards scene-setting images, often overhead views from drones, that then give way to more intimate environmental portraits. Many of the drone landscape images are further indicated with GPS coordinates neatly tucked into the corner of the page, further evidencing the care and attention to documentary detail that Bibel deploys.

A major merit of the book is how it is multi-modal. One of the more interesting dimensions is its inclusion of interview texts, interspersed throughout and often corresponding to some of the environmental portraits. The pages are nicely set off with a different trim size and provide just enough material for the reader to consider without overwhelming the reader with detail. The upshot of these is that it further brings home the lived realities, and indeed struggles of, for example, living life in constant fear/preparation for the next flood or other climate catastrophe.

Bibel has produced a thought-provoking cultural reading of the landscape under the conditions of climate change, posing important questions along the way. The use of such a wide range of photographic techniques will be an inspiration to others and compliment the ambitious use of materials within the context of the design of the book itself. Throughout, technical precision in the images is just as evident as in the execution of the book project. Uncertain Homelands further succeeds on the level expanding the horizon of what a photobook about climate changes can be, achieving both aesthetic and scholarly rigor.

Brian O’Neill is a sociologist, writer, and photographer from Phoenix, Arizona.

____________

Nora Bibel: Uncertain Homelands

Photographer: Nora Bibel (Born in 1971, lives in Berlin)

Publisher: The Eriskay Connection, © 2024

Languages: English (with German translations)

Texts: Dr. F. Hattermann, Rosa-Stella Mbulu, Prof. Dr. Bruno Merz, Sapariah Saturi, Dr. Christiane Stahl

Conducting and editing interviews: Nora Bibel

Translations: Michael Grubb, Julia Merk, Donna Stonecipher

Lithography: Sebastiaan Hanekroot (Colour & Books)

Production: Jos Morree (Fine Books)

Printing: Wilco Art Books (NL)

Swiss-bound hardcover, 230 × 320 mm, 308 pages

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment