Review by Brian Arnold ·

Pres-tige /pre ste(d)ZH

Noun

Widespread respect and admiration felt for someone or something based on perception of their achievements or qualities

John Cutter, one of the principal characters in Christopher Nolan’s 2006 film The Prestige, tells us there are three basic acts composing any magic trick. The first is called The Pledge; the magician shows you something ordinary (a deck of cards, a bird, or a man) and confirms to this is indeed as it appears to be. The second act is The Turn. Here the magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary, like vanish into thin air. Most of the audience is looking for the sleight of hand but if the magician really uses misdirection, the audience will be left dumbfounded. Finally, the last act is The Prestige, the great reveal, when that which disappears comes back, but with the audience still left in wonder. Again, the audience wants to the know the truth, but Cutter tells us we will never work it out, “because of course you aren’t really looking, you don’t really want to work it out. You want to be fooled.”

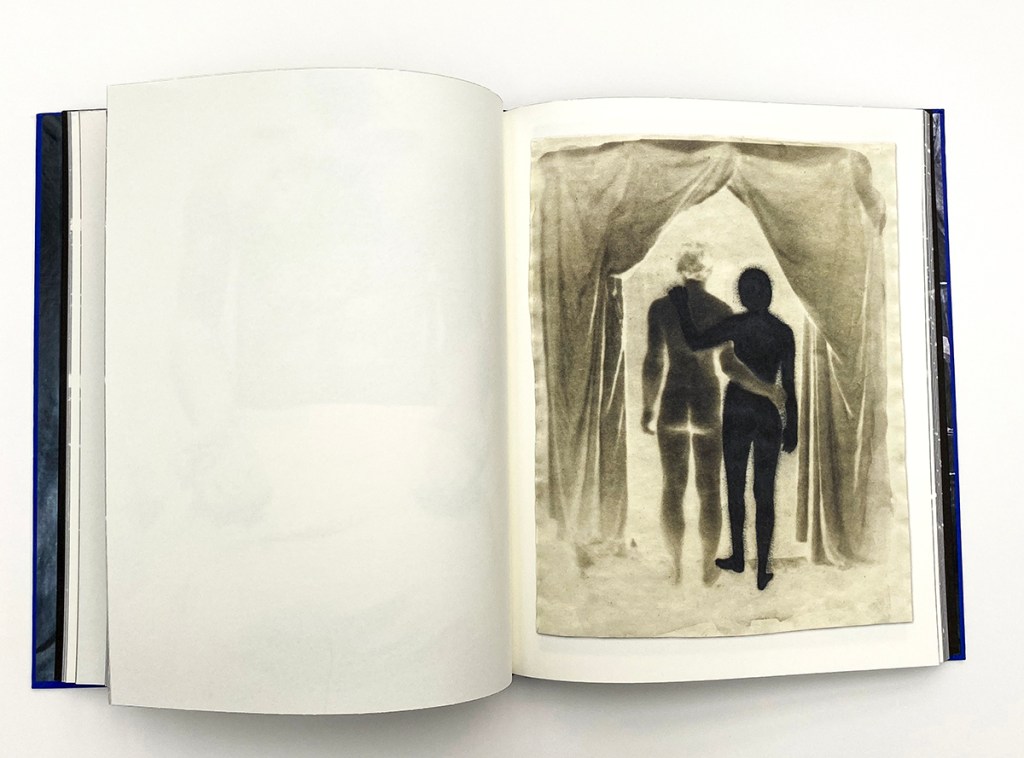

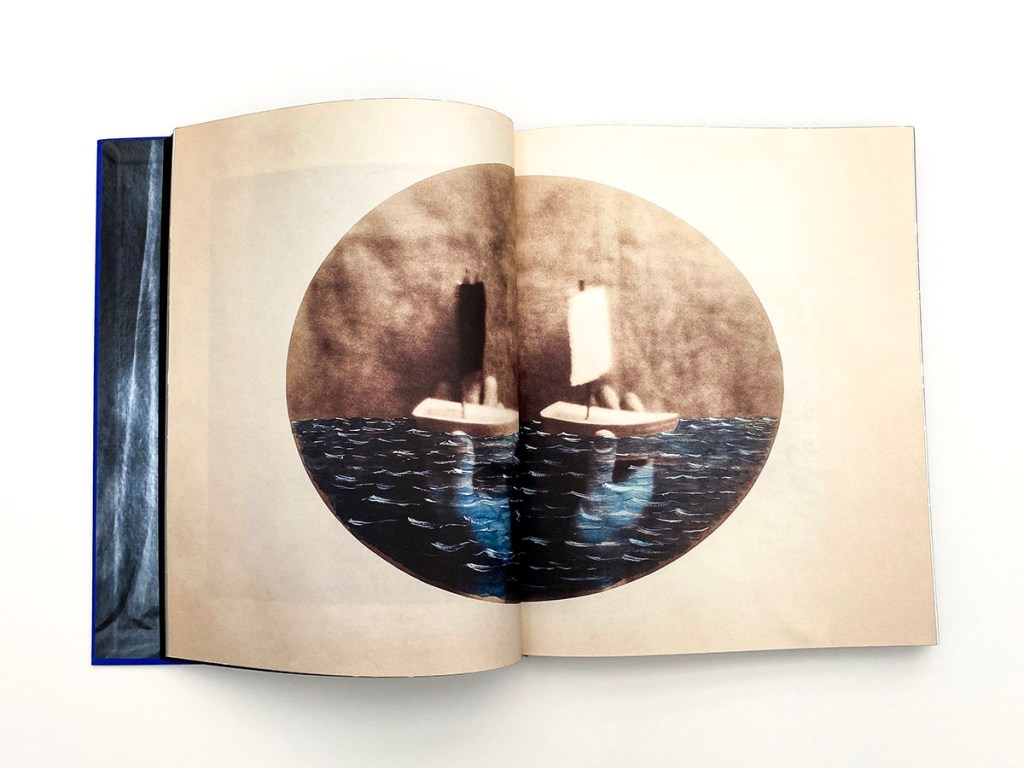

Like most of Nolan’s films, The Prestige is amazing, and offers confounding layers of deception and perception, really defining the nature of magic as being about these contradictory ways of seeing. Photography, at least if you think of it in its earliest years, must have seemed like incredible magic, a parlor trick that would provide lasting entertainment and insight, a sleight of hand that at once made the world more real and more abstract. Imagine the days long before television let alone the internet; your first tintype portrait or cabinet card must have felt like a revelation. When I first discovered photography, I was really drawn to artists that made magic and alchemy part of their subject (as a teenage punk rocker, it seemed more rebellious to think of photography this way – before I discovered it for myself, I thought all photographers were nerds or pornographers). Brooklyn-based artist Dan Estabrook has similar ideas and still embraces the magic and alchemy of photography. He also understands the medium as a tool for playing with perception and deception. Indeed, a great part of the appeal his new book Forever & Never is that it unashamedly relishes in these ideas – that photography is magical, that it can manipulate perception and deception, and that it can also elevate the simplest of objects and experiences into something that looks and feels extraordinary – really what Cutter is getting at when he talks about The Prestige.

I first learned of Estabrook’s work in the early 2000s. I was just out of grad school and teaching an alternative process class and found his salted paper prints while researching contemporary work done in historical photographic processes. A prodigy of the great Christopher James, Estabrook has made a deep investigation of early photographic processes a cornerstone of his work. I’ve long been a proponent of 19th photographic techniques (studio costs can be so much lower when you don’t need technology, just water and sun), but I also feel these early methods are also full of traps and tropes to be avoided (platinum/palladium prints can be totally gorgeous or a bit saccharine, depending so much of the aptitude of the maker). Part of what I find compelling about Estabrook’s work is that he embraces history and nostalgia, even exploring ideas that feel deliberately campy, but also brings a sly and compelling wit to his pictures, resulting in photographs that historian Lyle Rexer described as “antiquarian avant-garde,” (The past is not dead. It’s not even past).

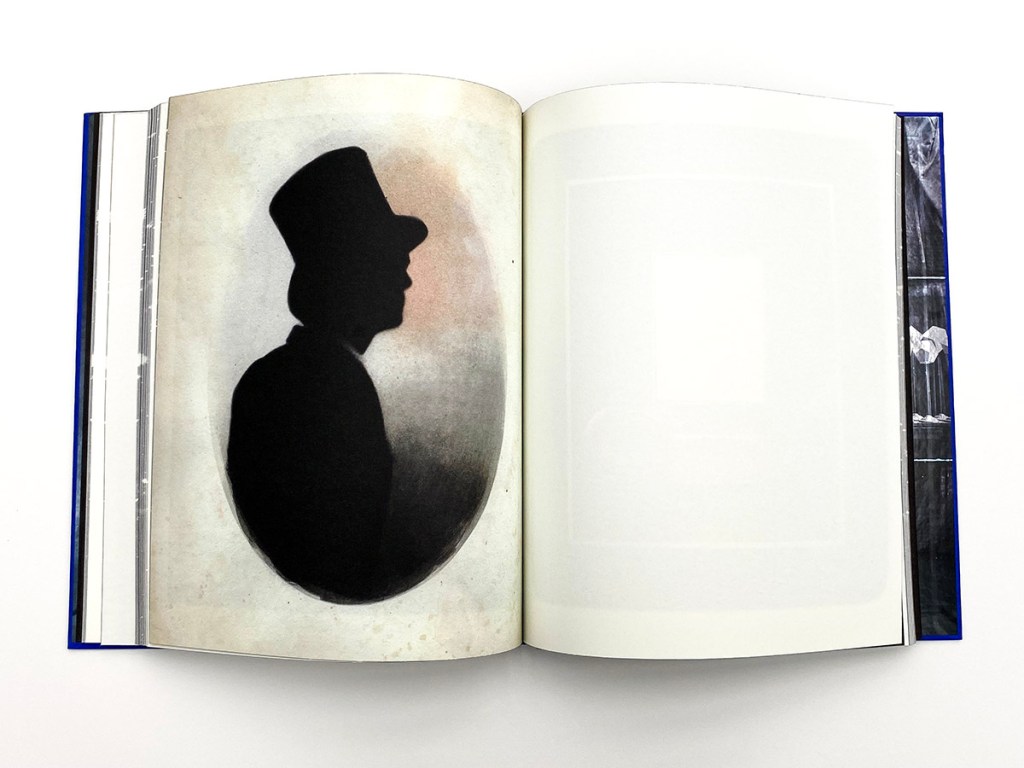

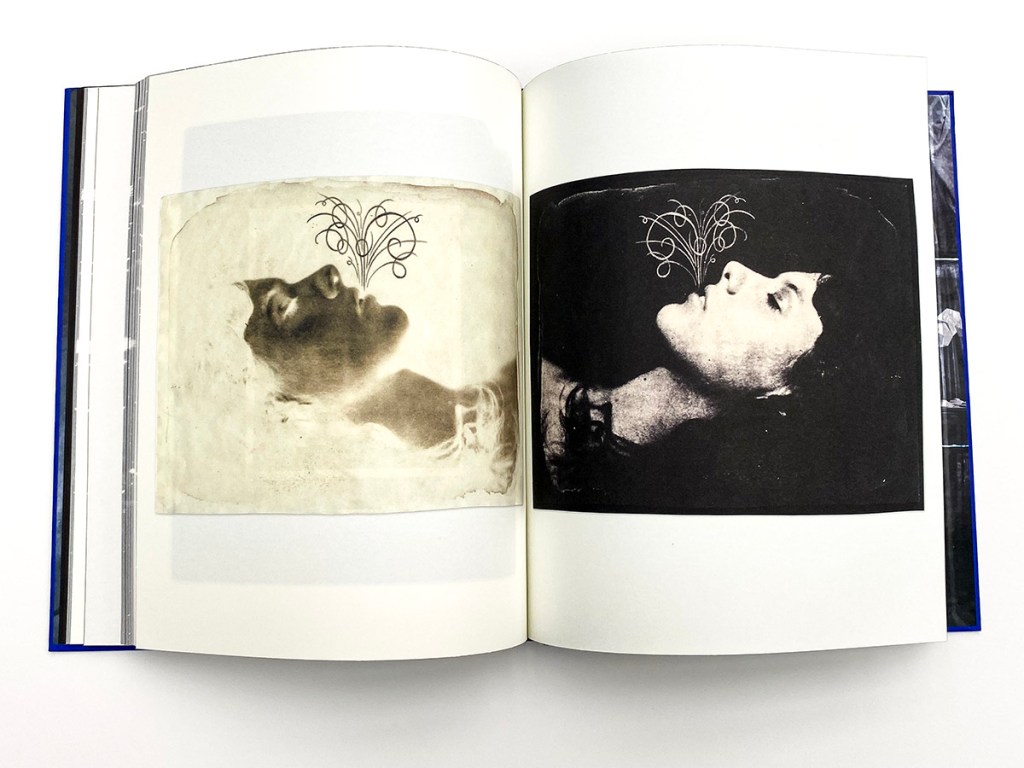

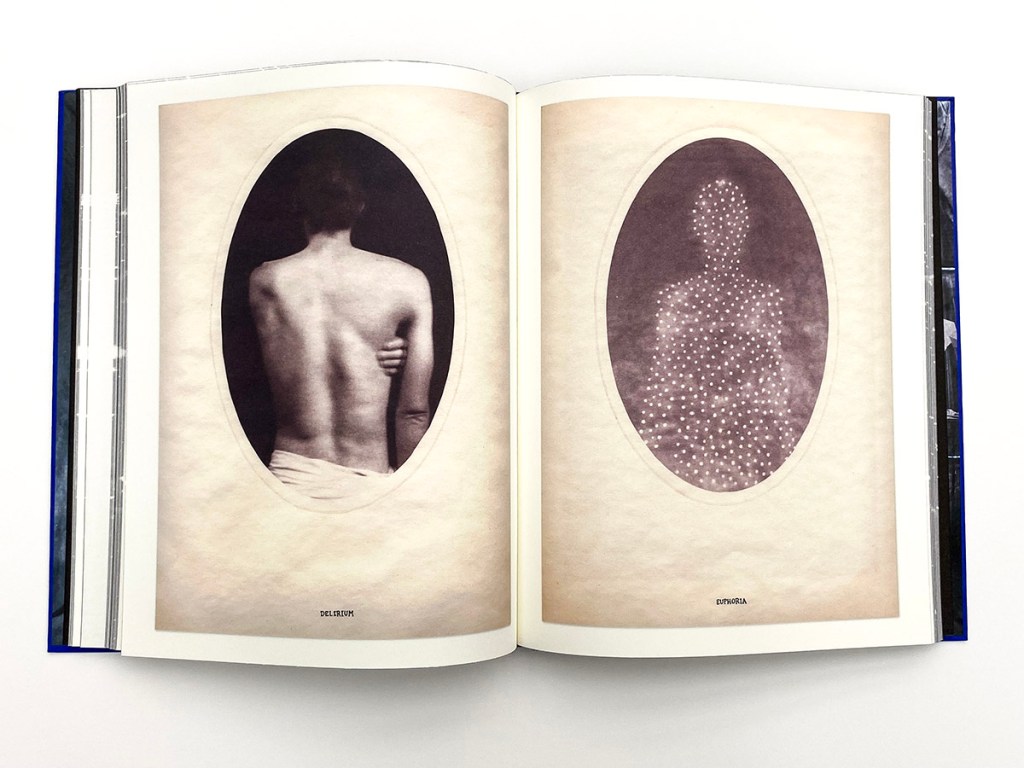

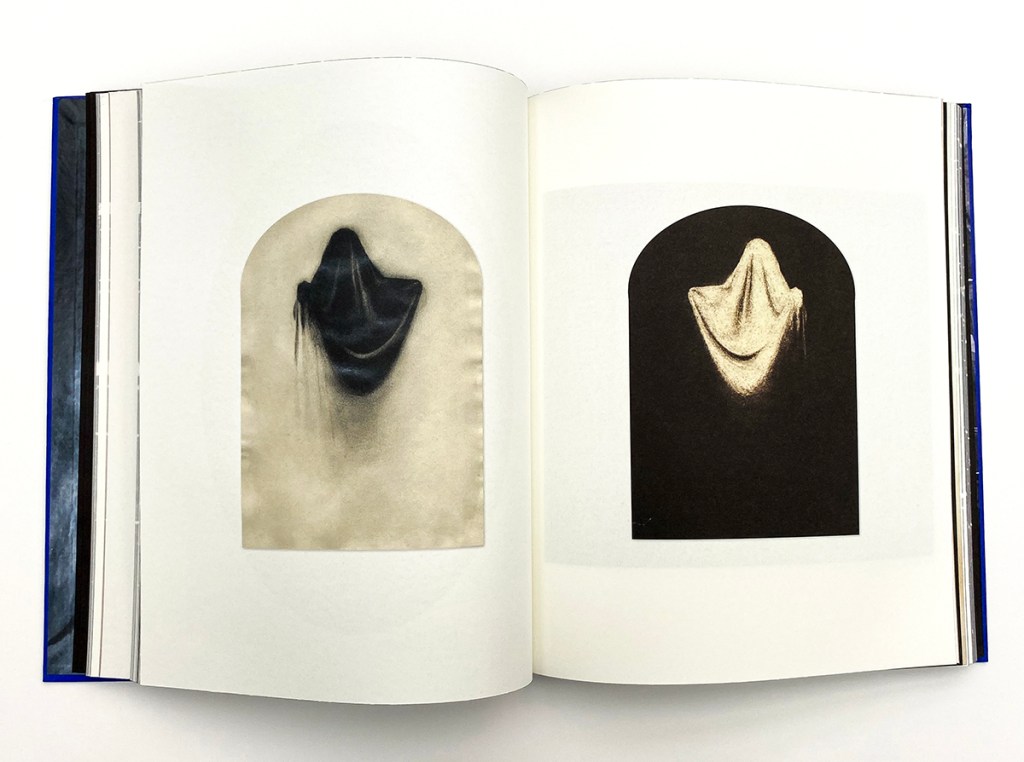

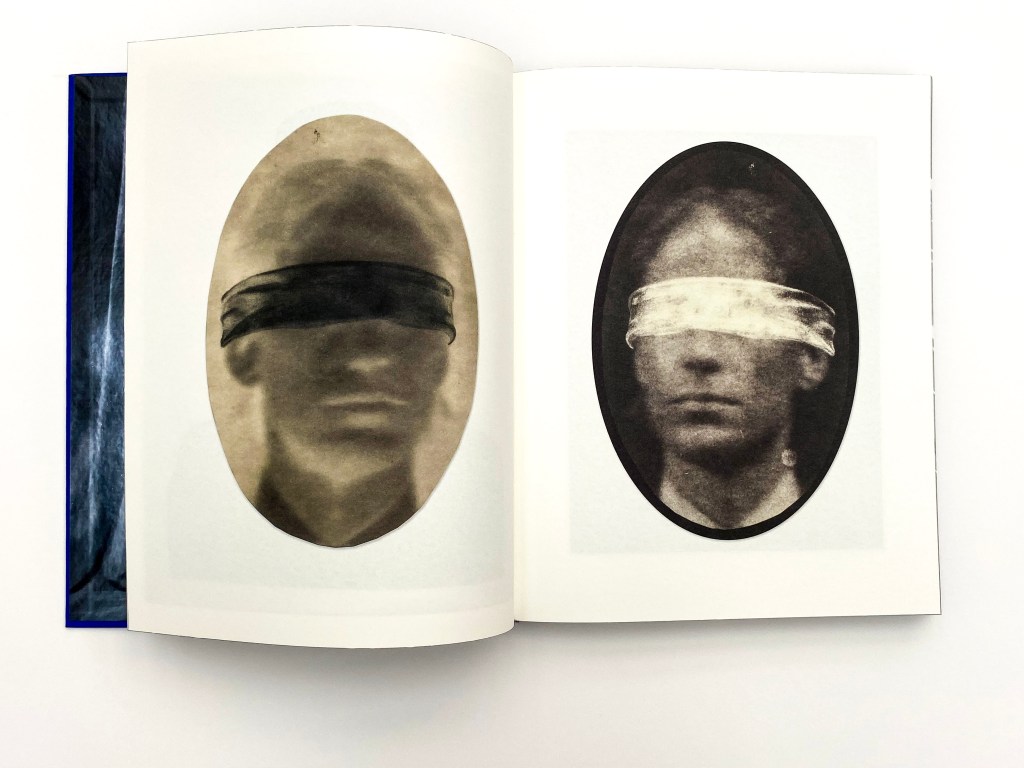

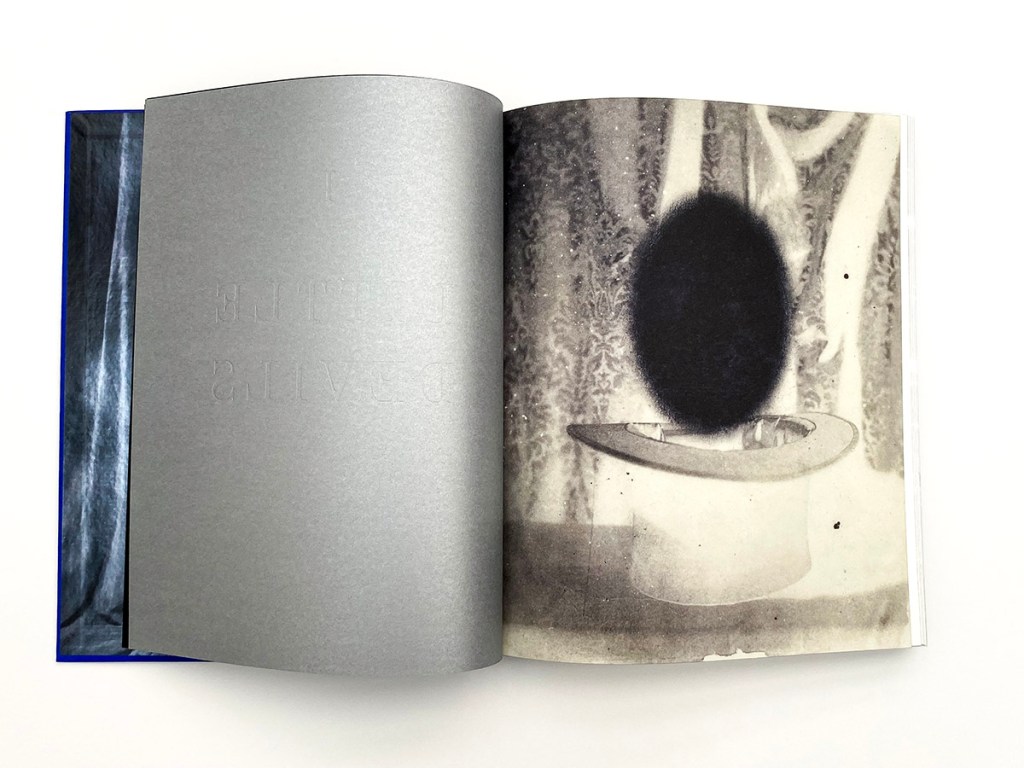

Forever & Never is a playful book, full of clever sleights of hands, a style of performance that feels akin to a middle school play, and complex ideas about the mysteries of life. Beautifully designed by Elana Schlenker, the book has a glowing cobalt blue cover, a mask of the artist’s face stenciled in the middle with a small hole burrowed between his lips. The bound pages are printed to make them look both like a tabletop stained with silver nitrate and a primitive map of the heavens. Opening the book, the endpapers are glossy and radiant pages depicting the artist’s studio, an illuminated mirror at the heart (appearing as though originally photographed in a wet collodion process). The following pages, a more traditional matt finish, illustrate a narrative of a man performing small, staged scenarios that explore the elusive mysteries of love, childhood, fantasy, death, mysticism, and photography. The book is divided into three chapters – Little Devils, Ghosts and Models, and Broken Fingers – and each of these is composed with pictures Estabrook made between 1999-2024 (personally, I love when photographers can demonstrate so much patience with their vision). Conceived as objects as much as images (one of my favorite attributes of alternative process photography), Estabrooks photographs use an incredible range of processes – calotype negatives embellished with graphite and an Xacto knife, rich and lovely palladium prints, touches of watercolor, albumen prints mounted on cardboard, and silver gelatin prints reconfigured with bleaches and toners. In his 25 years of photographing, there is one character that repeats throughout, his alter ego, a sort of magician adorned with a top-hat – appearing elusive but relatable, clever and creative, conceived as an everyman experiencing all the complexities of love and life in the 21st century while reflecting on the nature of photography, perception, and history.

To get a better understanding of Forever & Never, I felt the need to contextualize Estabrook’s pictures, because ultimately, I feel the central character of his work appears throughout photographic history, a sort of Victorian every man. I tried to think of list of photographers who represented a similar character and came up with William Henry Fox Talbot, Edward Steichen, Paul Outerbridge Jr., Tony Oursler, the early pictures of Robert and Shauna ParkeHarrison, and even in the 19th century reenactments of John Coffer. Estabrook’s style, while polished and performative, also strives for a historical vernacular, perhaps best seen in a series of ovular portraits that look something like cabinet cards but with captions like “Shortness of Breath,” “Hear Rate Increase,” and “Euphoria.” Embracing of the vernacular got me to add a couple more things to this list – The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult , the brilliant exhibition and book organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Clément Chéroux, and some of the photographs I collected from antique malls. All of these comparisons do help clarify Estabrook’s ideas and methods, but it’s also clear that he has developed an entirely unique approach to photography, one that reminds me that the heart of creativity is play, a childlike spirit that still believes in magic.

Contributing Editor Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

____________

Dan Estabrook – Forever & Never

Photographer: Dan Estabrook

Text: Linda Johnson Dougherty, Arnold J. Kemp, and Lyle Rexer

Publisher: Art Suite

Designer: Elana Schlenker

Language: English

Smyth sewn with a die cut hardcover; 212 pages, 90 plates, 6 die cuts; 11 3/8 x 9 1/8 in. (28.83 x 23.11 cm.); ISBN 979-8-89443-361-5

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment