Review by Brian Arnold ·

“Her art was mischievously unruly and luxuriously disruptive; she was interested in confronting the idea of ‘experience’ to directly address issues around feminism, sexuality, classicism and austerity, death, disease, and beauty.”

Laura Smith

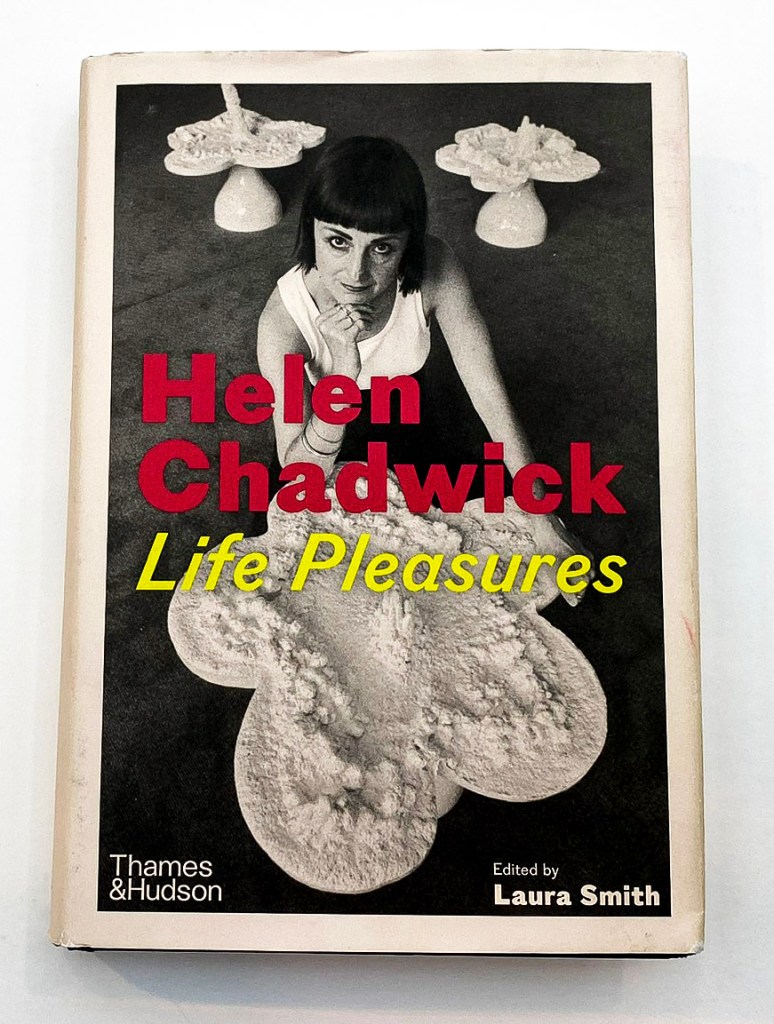

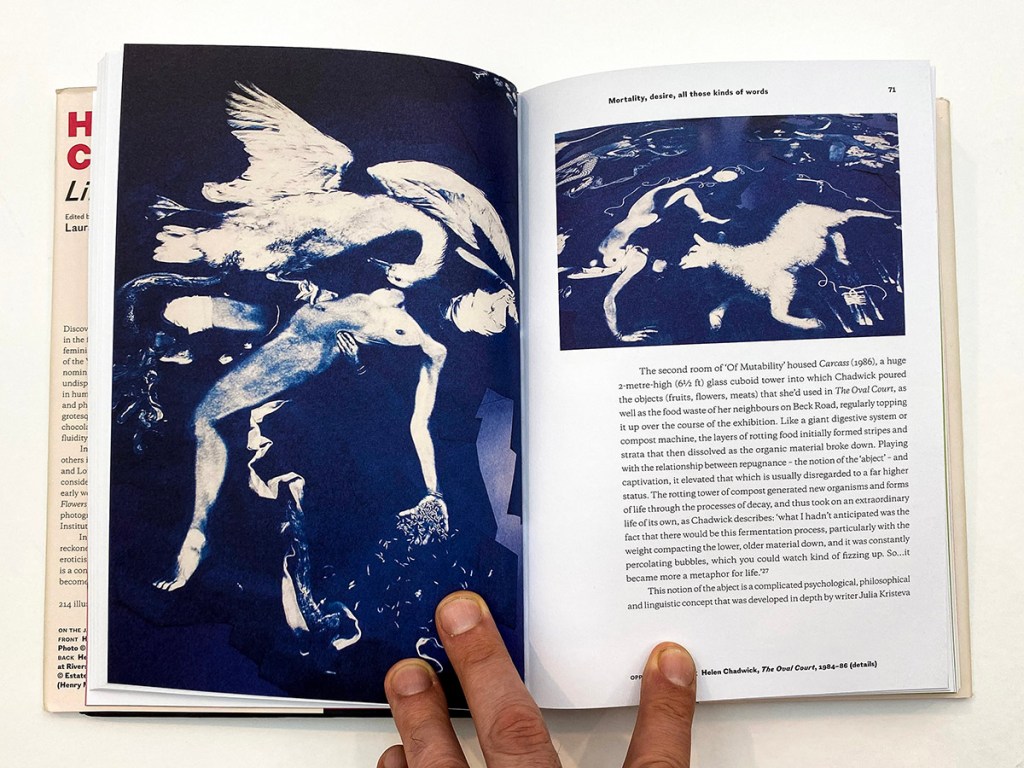

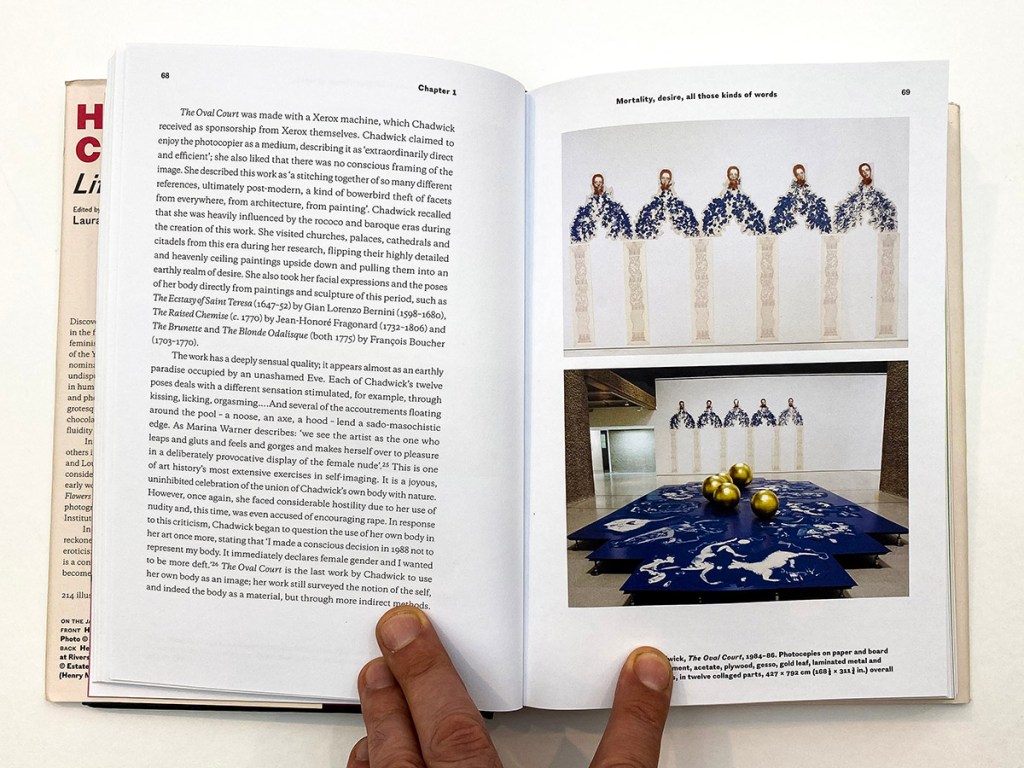

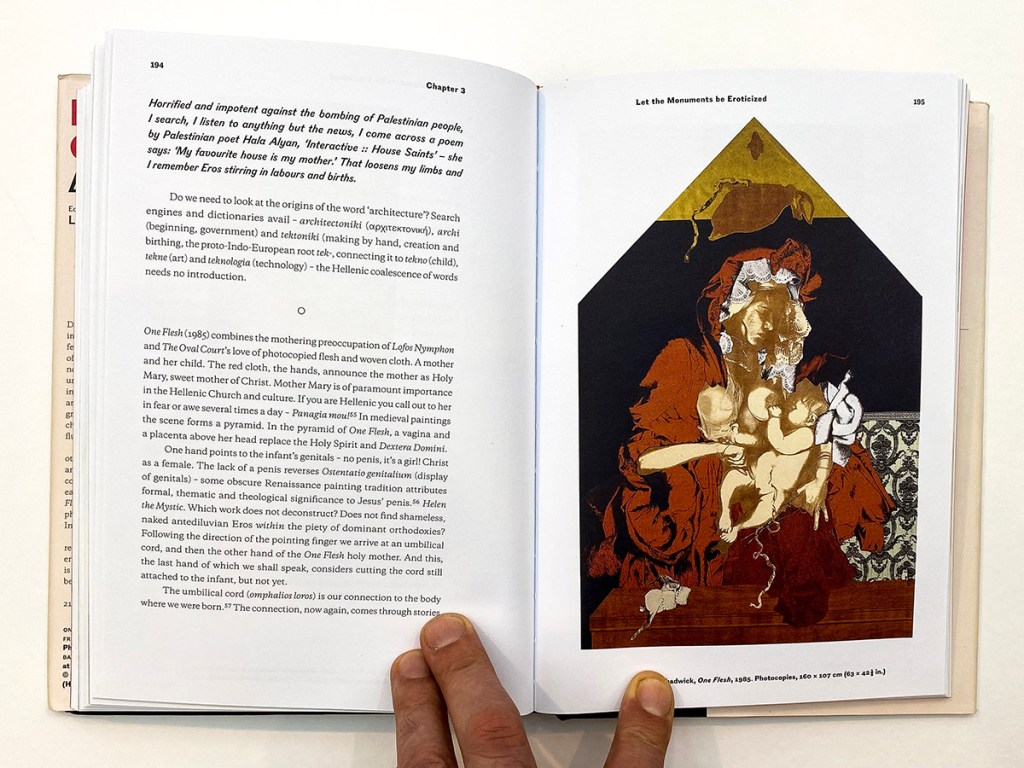

The first work I experienced by Helen Chadwick was The Oval Court, and I only saw it in reproduction, as part of an art history slide library in Western New York. I knew nothing about Chadwick but this piece, and only experienced it crudely and without explanation, but I still loved it. Composed entirely with Xerox copies, I shared these slides of The Oval Court with my students frequently because I thought it a fantastic example of photographic innovation using only the most basic elements and tools, no Hasselblad or Iris printer. If you are unfamiliar with it, the piece is a series of allegoric collages, life-size but assembled from prints churned out of an office copier. The collages are laid out on a platform with five gold orbs resting between them. The Xerox images are incredible, all created in a color resembling a cyanotype and literally hundreds of them, printed on cheap reams of copier paper. These prints are collaged together to create life-size tableaus, each spinning fantastic narratives centered around Chadwick’s nude body.

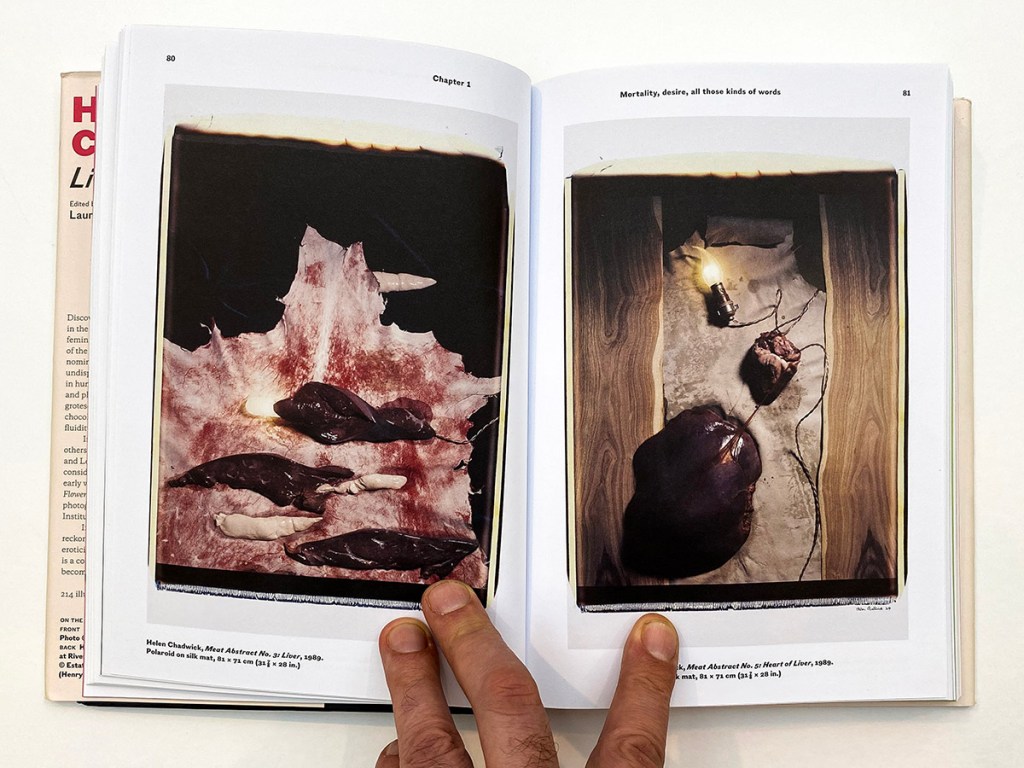

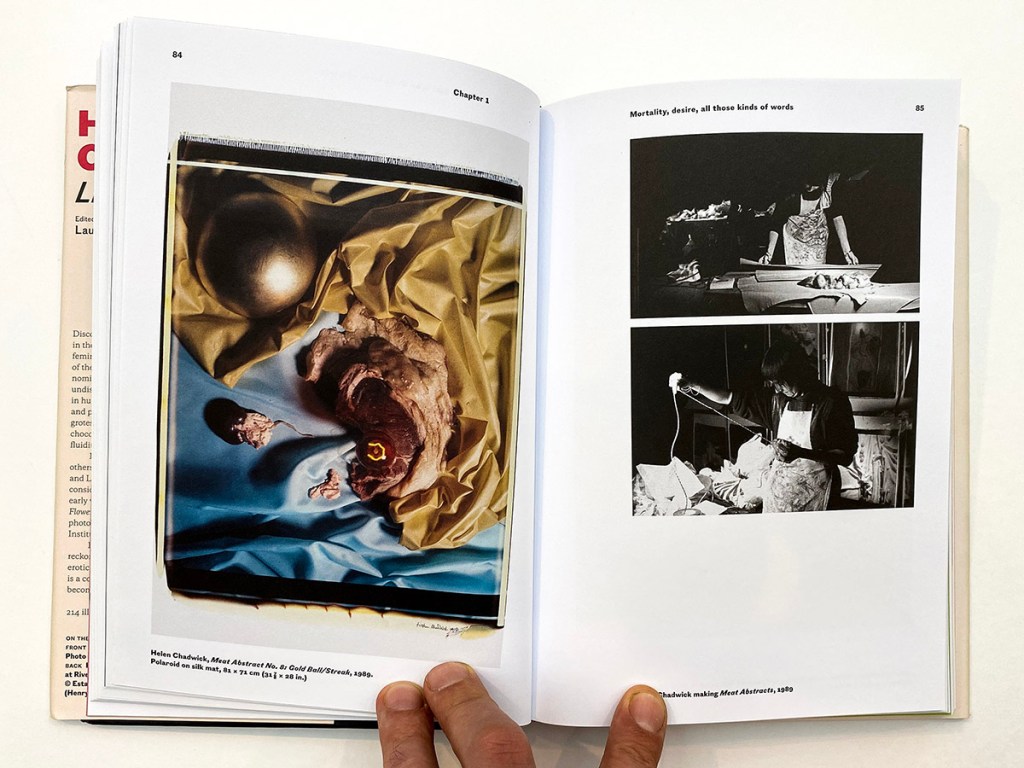

The compelling part of these tableaus are the other items Chadwick posed with, each charged with clear, bold symbolism. As she did with much of her work, Chadwick juxtaposed extremely provocative materials and forms with her body. Early on it was raw meat, latex, and electric burners from a kitchen stove. In The Oval Court, she selected images thinking more about allegory than confrontation. In these blue-toned collages, Chadwick’s nude body appears drowning underwater, writhing beneath the surface with things like a lamb, a rabbit, an array of flowers and insects, an axe, and fishnet stockings. These objects and the movements of her body appear deliberate and rigorously conceived. The five gold orbs (the senses?) appear divine, like buoys that might save her before she drowns. With all these elements at play, The Oval Court explores deeply layered ideas about religion, sexuality, and identity. Even seeing reproductions of this work using only a loop and a lightbox, I was mesmerized by her shamanic images, the artist literally rolling her naked body through art history and religious allegory.

The Oval Court launched her into international fame, a career-defining piece that was lauded and praised by art critics but was also extremely controversial in other circles. Chadwick had already built an impressive career as an artist and educator, but with this piece the world took note. Shortly after The Oval Court was first shown, Chadwick as nominated for the Turner Prize (she was the first woman considered for this prestigious award), and she also started receiving invitations to show her work around the world. The Oval Court was compared to Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, but it also outraged feminists who felt she used her sexuality in ways propagating patriarchal oppression. Like Andrea Dworkin in the United States, earlier feminists in England felt that any depiction of female nudity continued to promote objectification. Indeed, there was so much discussion about Chadwick’s nudity that after The Oval Court she abandoned this practice. It’s not that she agreed with the critics, but that she felt too much time was spent on these discussions and it was distracting from the real ideas driving her work.

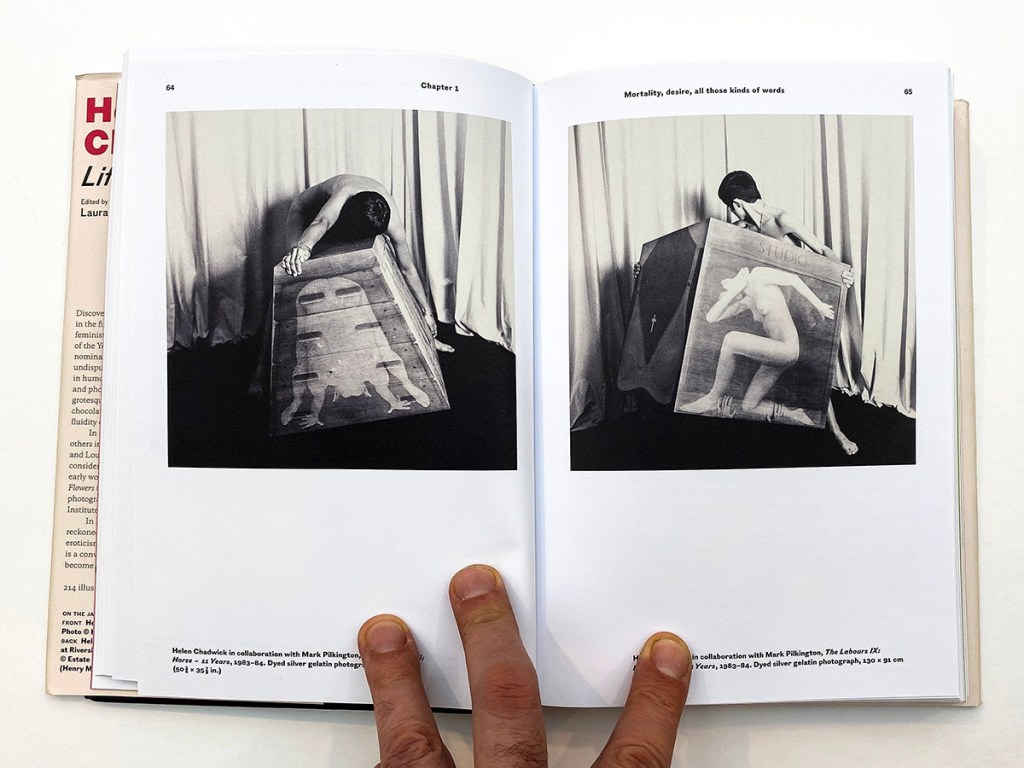

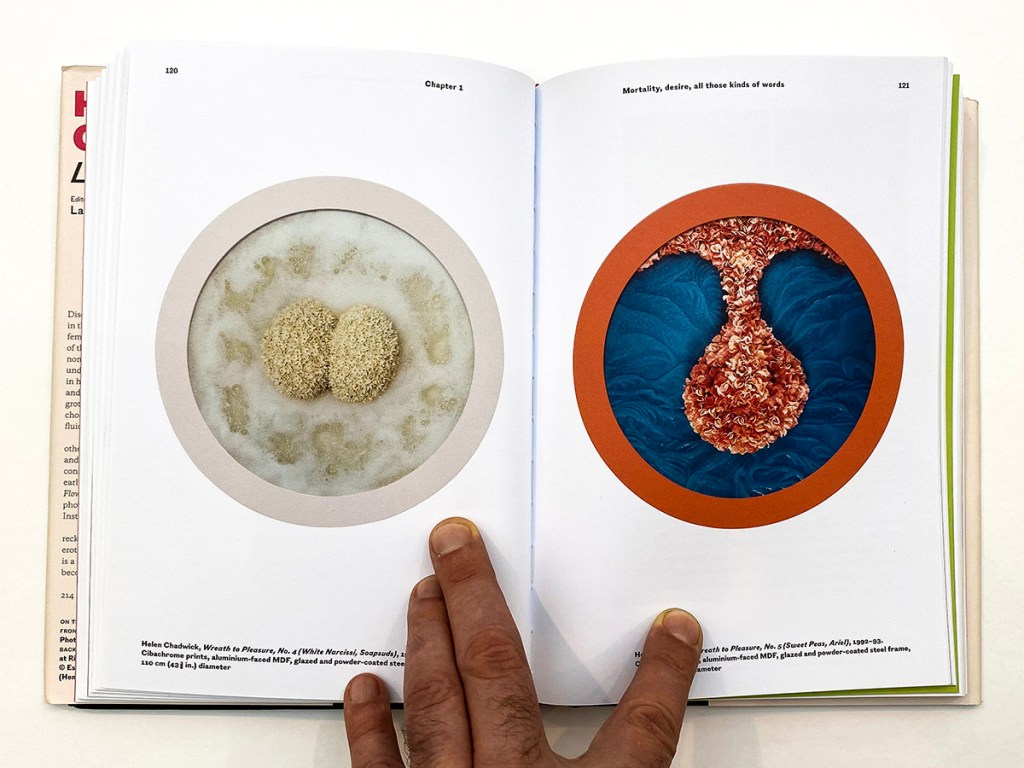

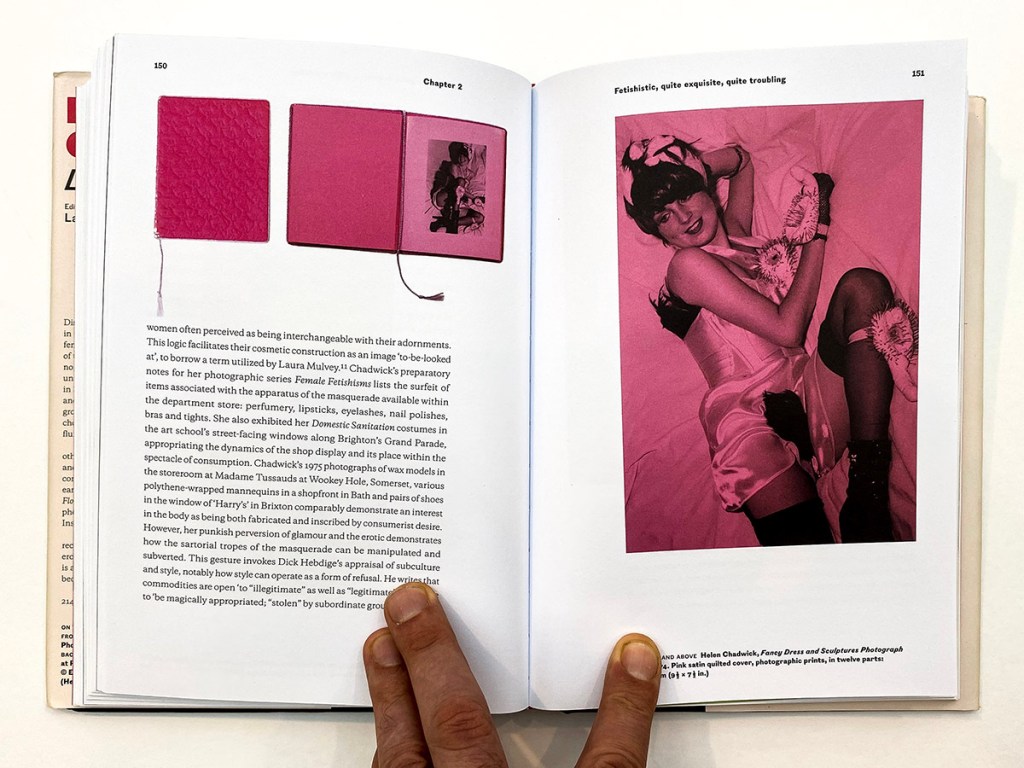

I’ll be honest and say that I haven’t thought too much about Chadwick or The Oval Court since I lost access to that slide library over 20 years ago, at least until I had the chance to read the new book edited by Laura Smith, Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, published by Thames & Hudson in conjunction with a retrospective of Chadwick’s work at the Hepworth Wakefield Museum in West Yorkshire. The book offers a detailed account of Chadwick’s work and career. The introductory essay by Smith traces the artist’s development from her early days as an art student at Brighton Polytechnic (1973-1976) to her untimely death at age 42 (1996). From her earliest work, Chadwick demonstrated a clear vision – working to break down gender roles and social mythologies – with a remarkable discipline for learning materials, expressing her ideas in an incredibly diverse range of media including photography, latex, snow, plaster, fur, and raw meat. So much of Chadwick’s work played with contradictory feelings and sensations – equally seductive and revolting, simultaneously embracing beauty, disgust, life, and death. The Oval Court was truly a breakthrough piece for Chadwick; much of her early work was didactic and offered simple social critiques, but her mature work presents much more nuanced and complex ideas about identity, sexuality, art history, religion, and vulnerability. Smith presents all of this with the same critical depth, offering great insight into the artist’s major works – bizarre, interesting, and luxurious pieces like Glossolaliaand Piss Flowers – but also stressing the important of Chadwick’s drawings, sketchbooks, and student work.

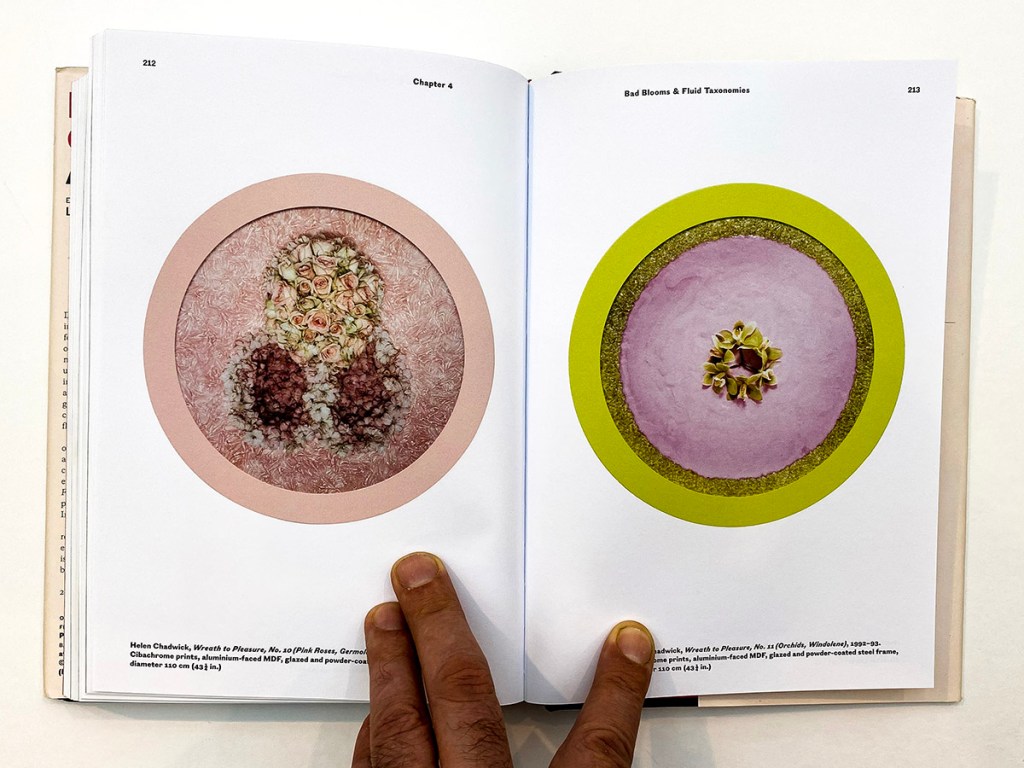

In addition to Smith’s introduction, Life Pleasures shares two other essays. The first of these, “Fetishistic, quite exquisite, quite troubling” by Philomena Epps, explores Chadwick’s Greek roots (Chadwick’s mother and father met in Athens during World War II), emphasizing that the artist’s vision is rooted in some of the oldest symbols and allegories of Western civilization. Epps also offers a close reading of Chadwick’s hand gestures, pointing out the deliberately arcane symbols the artist shaped with her hands. The last essay, “Bad Blooms & Fluid Taxonomies” by Katrin Bucher Trantow, is devoted to Piss Flowers, castings Chadwick made of her urine during an icy residency at Banff. The book concludes with a series of short testimonials, contributions by people as interesting and different as Mark Hayworth-Booth, Peter Gabriel, and Cosey Fanni Tutti, each stressing the importance of Chadwick in their own professional development.

I love Chadwick’s self-defining phrase “consolatory nonsense” because to me it implies mischief – “mischievously unruly,” as Smith says – a term that perfectly encapsulates her vision. Mischief delineates bad behavior, but nothing delinquent or destructive, perhaps playful instead, describing a prankster rather than a villain. In many ways her work is indicative of social and artistic trends of the 1970s and 1980s but nevertheless remains relevant today; Chadwick rebelled against the mechanisms of patriarchy long before #MeToo and advocated for true self-possession and sexual ownership. She rejected easy answers and comfortable narratives and demonstrated that true liberation requires confronting discomfort rather than seeking consolation. Chadwick’s brief but luminant career challenged us to examine the intersections of beauty and repulsion, mythology and materiality, the sacred and profane – tensions that still characterize our political and social discourses today. What emerges from Life Pleasures is not just a record of Chadwick’s unique oeuvre, but a reminder of art’s ability to express our most deeply held feelings about body, gender, and identity.

Contributing Editor Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

____________

Laura Smith (ed.) – Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures

Artist: Helen Chadwick

Publisher: Thames & Hudson

Editor: Laura Smith

Forward: Marina Warner

Essays: Katrin Bucher Trantow, Maria Christoforidou, Philomena Epps, and Laura Smith

Interview: Laura Smith with Luisa Buck and David Notarius

Perfect-bound hardcover: 170 x 240 mm (6.7 x 9.5 in); 272 pages; English; ISBN: 9780500028889

____________

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment