Review by Gerhard Clausing •

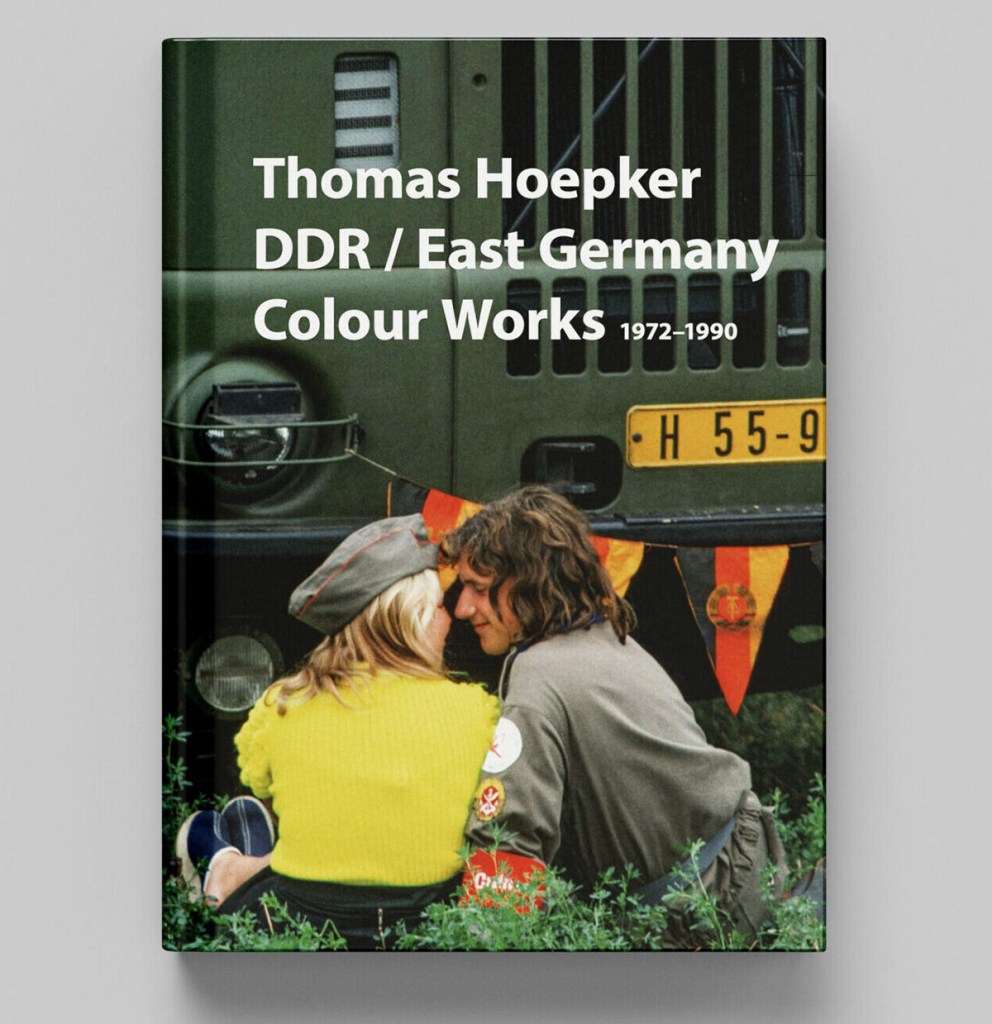

Thomas Hoepker’s DDR / East Germany – Colour Works 1972–1990 is a remarkable photobook, not because it reveals shocking new truths about the German Democratic Republic, but because it insists on looking carefully, patiently, and in color at a place that was more often described than seen. The photographs, so ably curated by the team of Thomas Gust and Anna Druga, working with Christine Kruchen, his widow, resist drama and condemnation. Instead, these images present East Germany as it appeared to careful observers (including myself) at the time: ordinary, highly constrained, oddly vivid, and deeply human.

Hoepker was the first West German photographer officially permitted to work in the GDR, beginning in 1974. This historical fact matters, but the photographs themselves never announce it. Instead, we encounter moments that feel almost casual: people waiting, walking, talking, standing beneath slogans, leaning against walls, or simply inhabiting spaces shaped by ideology and time. These images do not ask to be read as evidence; they ask to be looked at as photographs.

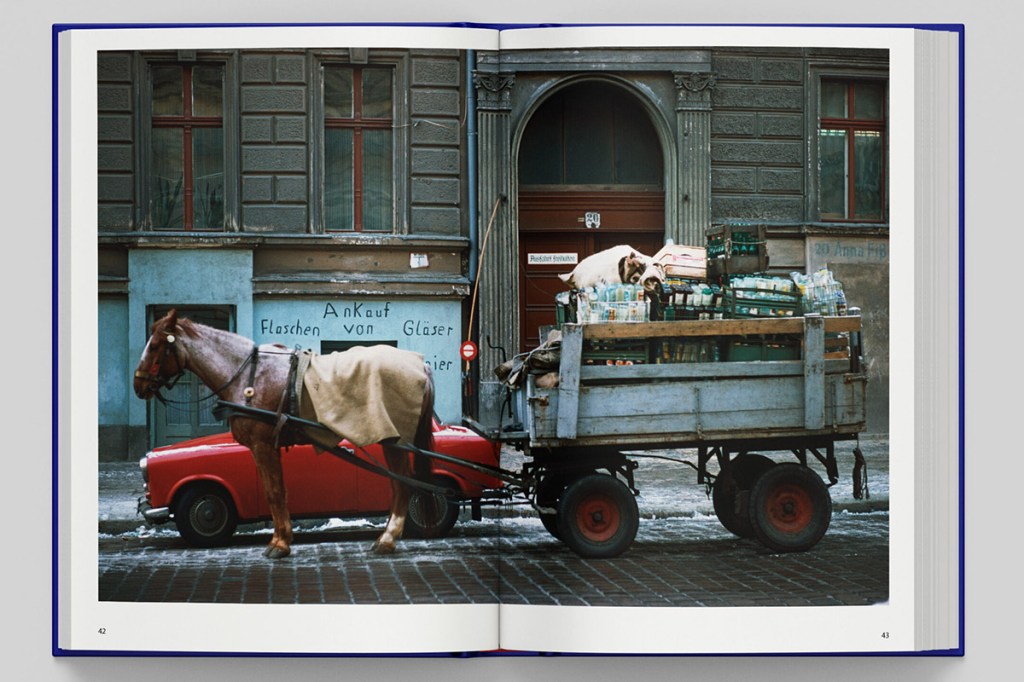

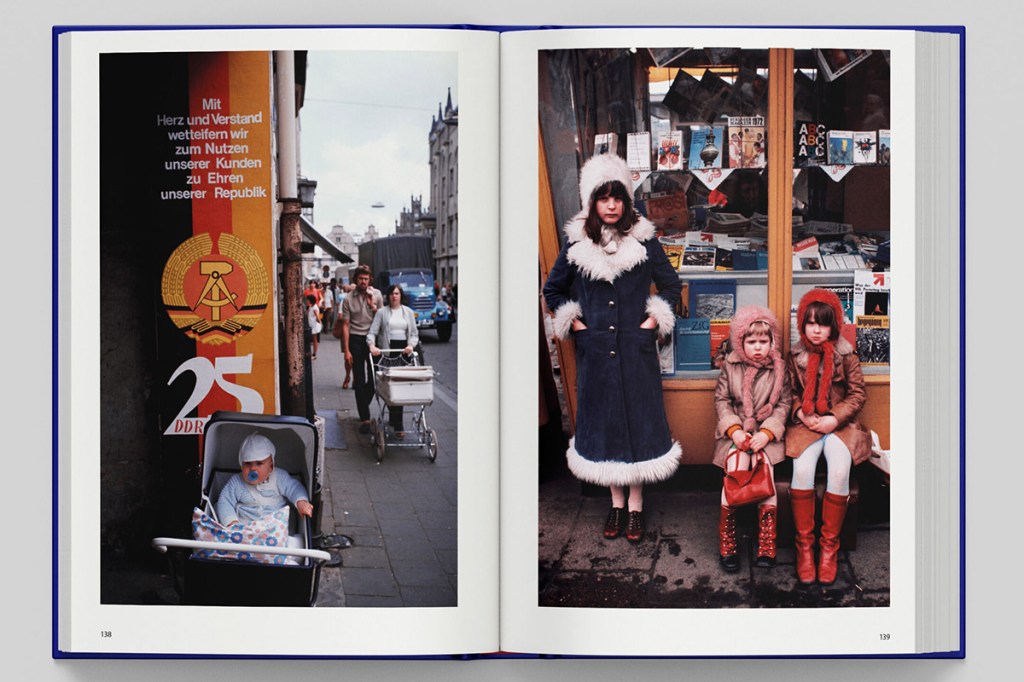

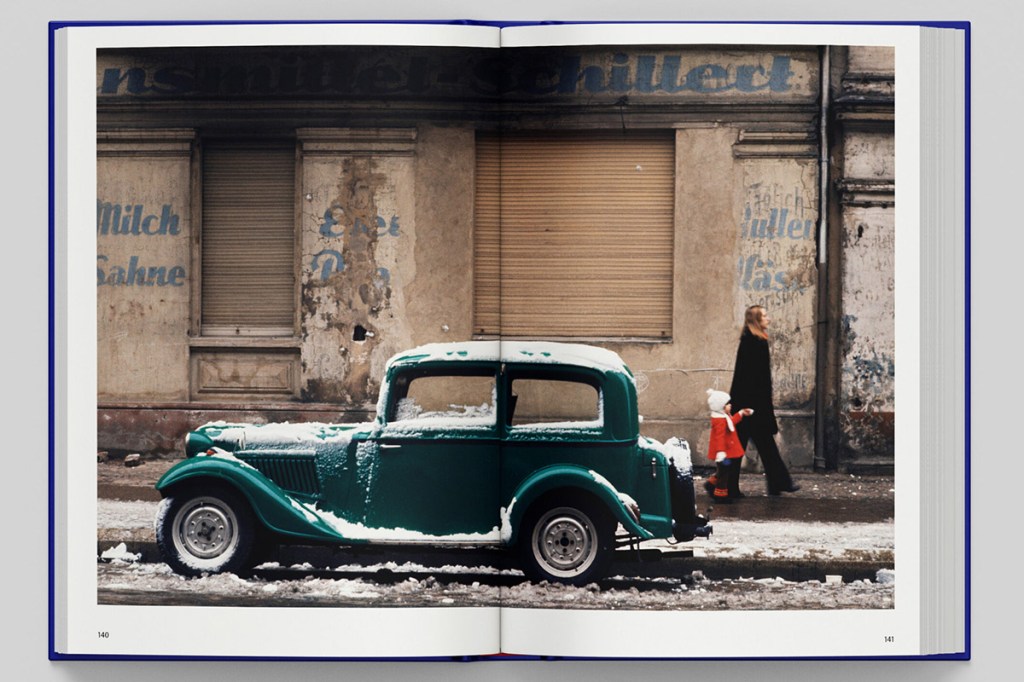

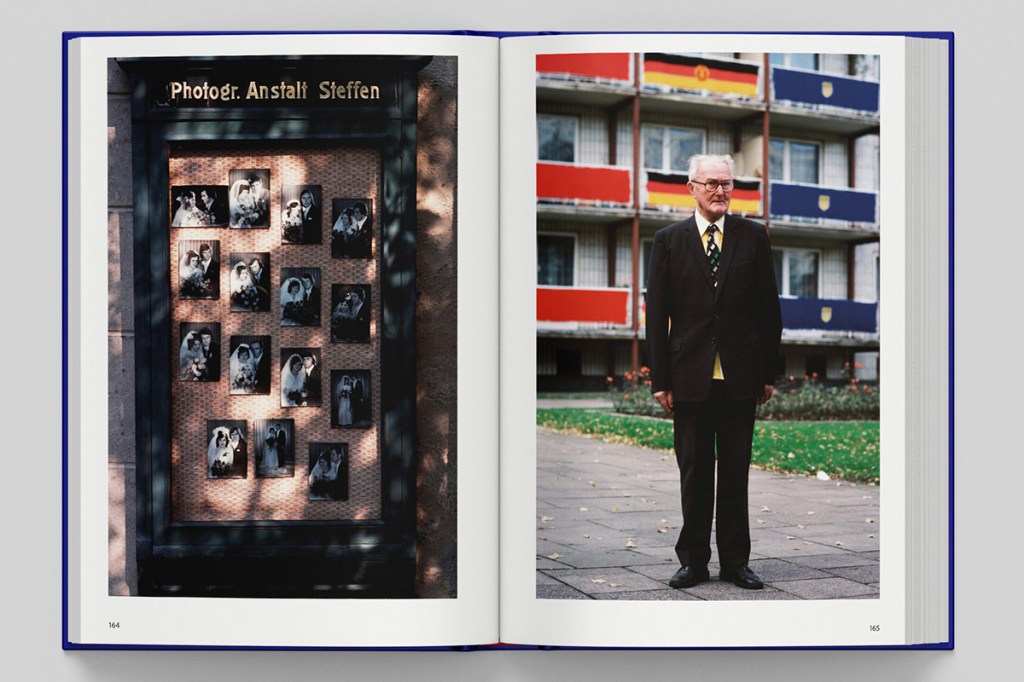

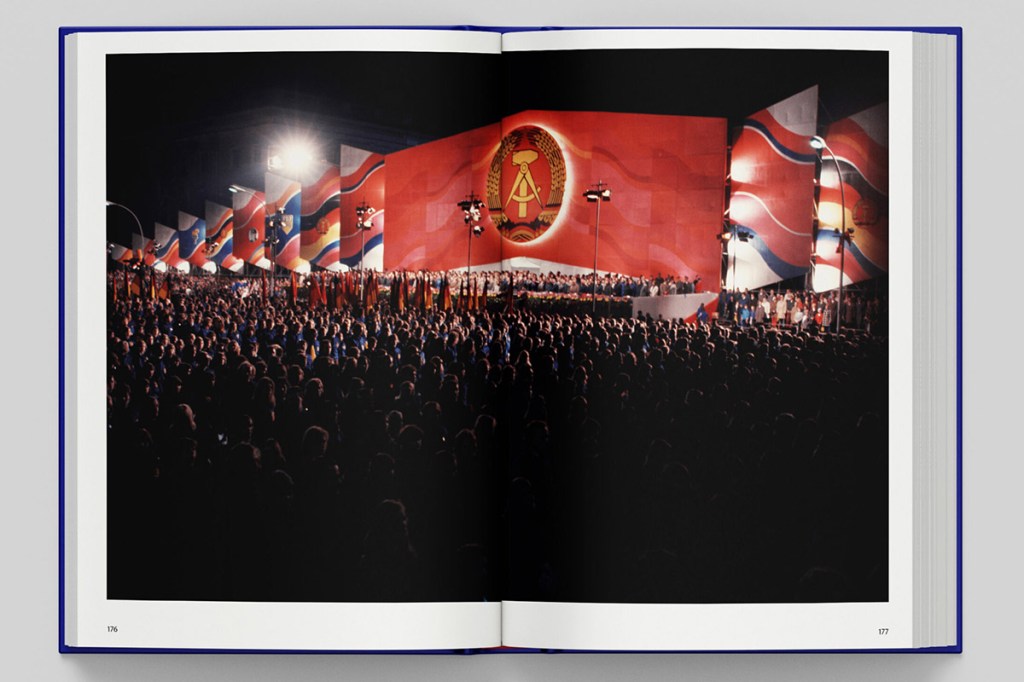

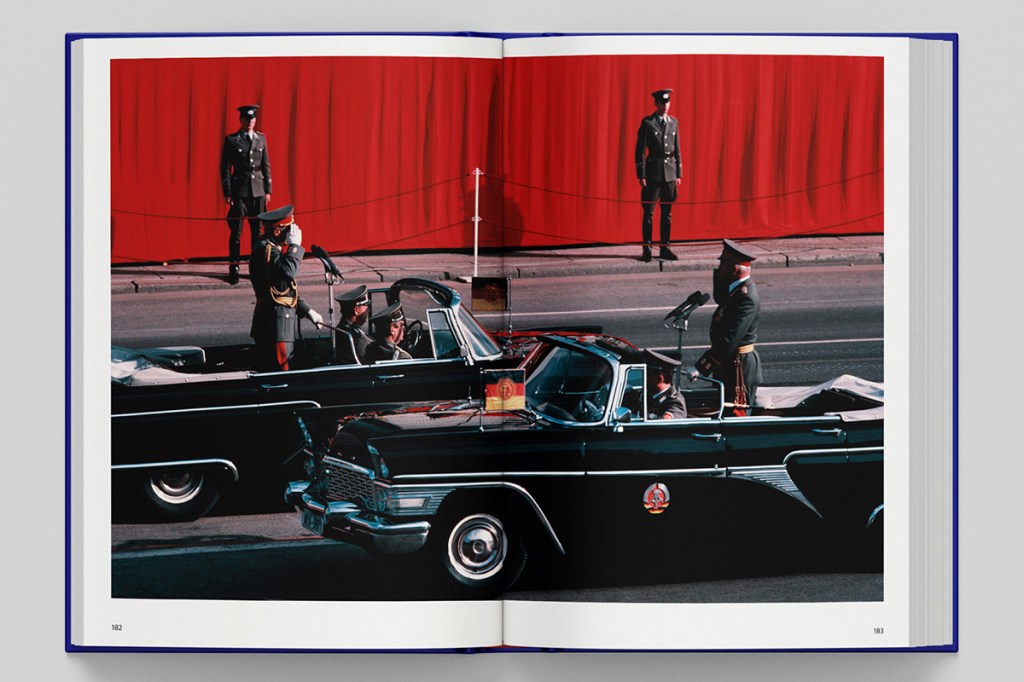

One of the defining features of this book is Hoepker’s use of color. Working with Kodachrome, he treated color not as decoration but as structure. Reds, yellows, and faded blues often dominate the frame, sometimes echoing the political symbols of the state, sometimes contradicting them. A red banner may shout a slogan overhead while a figure beneath it appears distracted or indifferent. In such moments, color becomes a form of quiet irony. The state speaks loudly, but life goes on in softer tones.

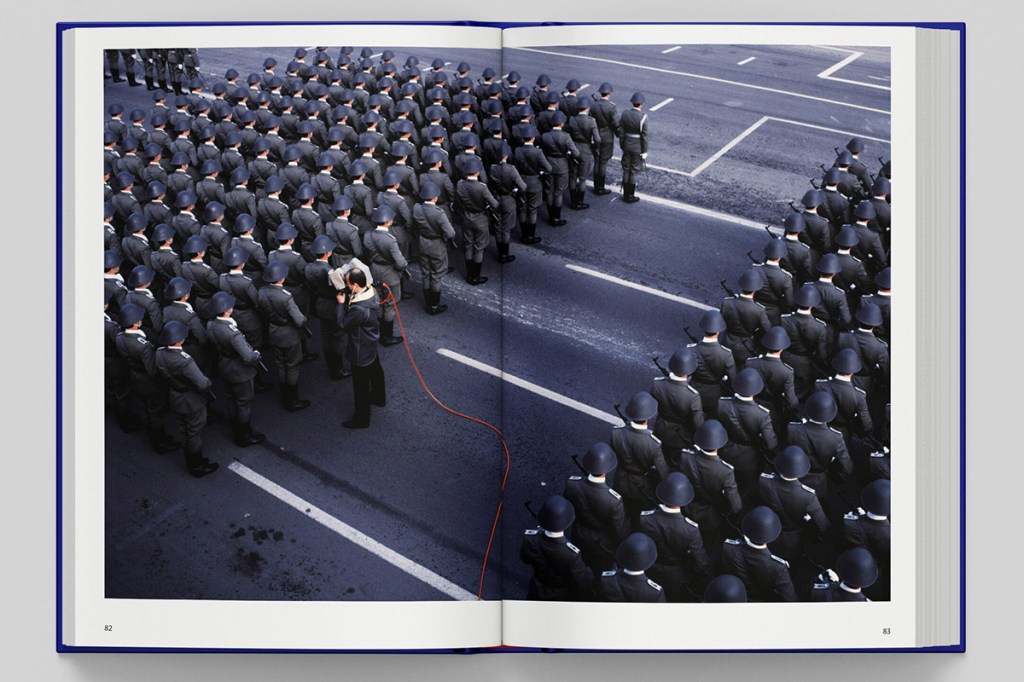

Hoepker frequently composed his images with a strong awareness of geometry and surface. Walls, windows, signage, and architectural lines divide the frame into orderly segments, within which human figures appear slightly misplaced or constrained. People are rarely centered as heroic subjects. Instead, they occupy the margins or appear uneasily within rigid spaces. This compositional choice subtly mirrors the social reality of the GDR, without needing explanation or commentary.

Equally important is what Hoepker did not show. There are no moments of overt violence, no scenes of protest or collapse until the very end of the period he documents. The absence of spectacle forces the viewer to pay attention to smaller visual clues: body language, facial expressions, worn surfaces, and awkward alignments between people and propaganda. A formal parade scene may feel strangely hollow; a crumbling façade can feel more honest than a freshly painted slogan.

Many photographs reveal Hoepker’s sensitivity to fleeting gestures. A glance sideways, a slouched posture, or a pause in movement becomes the emotional center of an image. These are not decisive moments in the conventional dramatic sense, but rather observational moments that accumulate meaning across the book. As we turn the pages, repetition becomes significant. Similar scenes recur with slight variations, creating a visual rhythm that mirrors the monotony and persistence of everyday life in a highly controlled society.

The sequencing of the book is calm and deliberate. Images are allowed space to breathe, and the design avoids unnecessary visual noise. This restraint encourages slow looking. The viewer begins to notice how often official messages occupy the upper portions of the frame, while human activity unfolds below. Over time, this spatial pattern becomes legible as a visual metaphor: ideology above, life beneath.

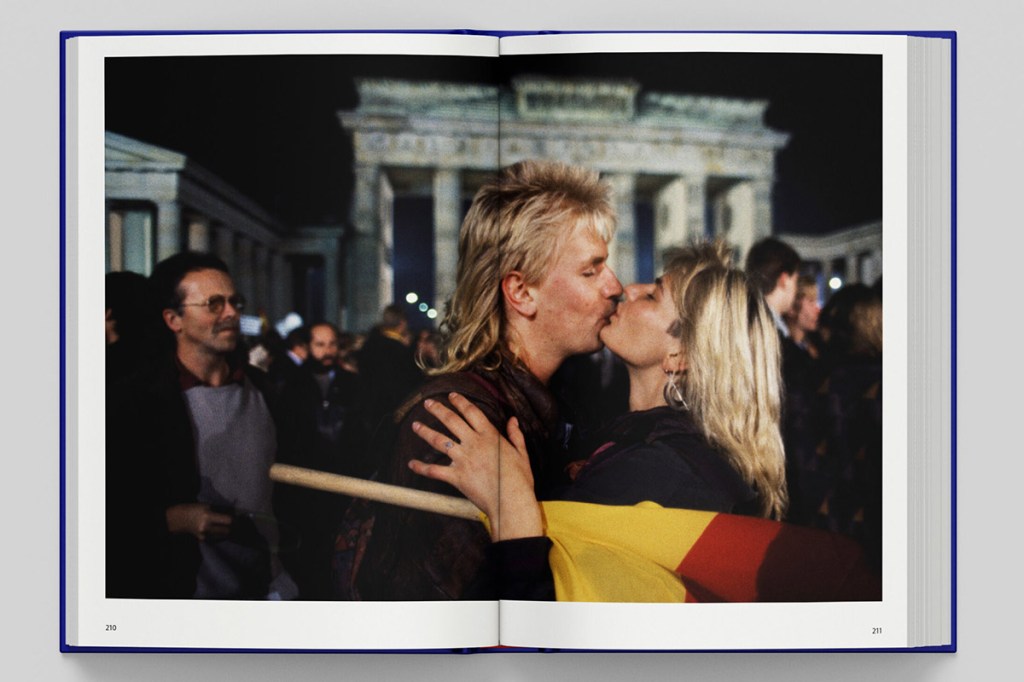

By the final sections, as the GDR approaches its end, Hoepker’s images do not suddenly become triumphant or celebratory. Instead, they feel reflective, even uncertain. The disappearance of a state is suggested not through grand events but through subtle shifts in atmosphere. The ordinary continues, even as history changes direction.

This photobook succeeds because it trusts photography itself. Hoepker’s images do not instruct the viewer how to feel, nor does his project rely on visual drama to carry meaning. His photographs operate through observation, composition, and color, asking us to recognize how politics enters daily life not only through laws and slogans, but through walls, streets, clothing, and posture. The essay by the illustrious Wolf Biermann, a rebel with an incisive mind, and the afterword by the important publisher Thomas Gust add fascinating perspectives to that amazing time and place.

DDR / East Germany – Colour Works 1972–1990 is a strong example of documentary photography that is neither cold nor sentimental. It shows how careful looking can reveal complexity without exaggeration. This book offers an important lesson: photographs do not need to shout to be politically and visually powerful. And most of all, the project demonstrates that even oppressive times are full of colorful personal moments to be remembered.

____________

The PhotoBook Journal previously featured a review of Thomas Hoepker’s Italia.

____________

Gerhard Clausing, PBJ Editorial Consultant, is an author and artist who investigates the role of culture and memory in visual art.

____________

Thomas Hoepker – DDR / East Germany – Colour Works 1972–1990

Photographer: Thomas Hoepker (1936-2024; born in Munich, Germany, lived in New York City)

Texts: Wolf Biermann, Thomas Gust

Languages: German and English

Publisher: Buchkunst Berlin, Germany; © 2025

Concept and Design: Thomas Gust, Ana Druga

Hardbound, with illustrated cover, 288 pages; 8 x 11.25 inches (20 x 28.5 cm); printed and bound in Germany by Gutenberg Beuys, Jochen Wanderer; ISBN 978-3-9819805-0-9

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

A clearheaded and intelligent review of an equally impressive book.

Sadly this piece of history was and is propagandized to death by all.

Very little was learned and it is being scattered to the winds, again to the detriment of the people involved.