Review by Brian Arnold ·

“Before long, my five senses and sixth sense began to function, and connections to various things and events acted in concert with the territory of the unconscious to produce the form called memory, and I began to trace the individual history that goes by the name, I.” Daido Moriyama – Memories of a Dog

Daido Moriyama was born in Ikeda, Osaka in 1938, on the eve of World War II. He was just 7 years old when the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The cultural transitions that shaped Moriyama’s early life were enormous, really unprecedented. Japan was devastated by the war, their cities in ruins and the people traumatized by a level of death and destruction never before witnessed. After their surrender, the Americans occupied Japan until 1952, overseeing their redevelopment and movement to democracy. New social orders were established which included rapid industrialization, important movements towards equal rights and women’s suffrage, and oppression and censorship by the American occupation.

In 1961, just 23 years old, Moriyama moved to Tokyo to work as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe, one of the most influential Japanese photographers to emerge after the war. With his baroque imagery, Hosoe developed a unique body of work that documented some of the tremendous cultural transformations of his homeland while exploring themes of death, sexuality, and traditional Japanese culture and spirituality, all grounded a deep appreciation of traditional theater. After 3 years, Hosoe let Moriyama go, thinking by this point it was much more important for the younger photographer to seek his own voice rather than continuing as his assistant.

This wasn’t necessarily an easy transition for Moriyama. He had no clients nor any idea how to start his own studio, his anxiety cascaded and led him to a deep existential crisis. After so much perseverating, Moriyama needed to make a decision – am I a photographer or not? – and went out and hit the streets with his camera, emerging with pictures in the vocabulary and style we’ve all come to know of him. Indeed, these pictures were awarded the New Artist Award from the Japan Photo Critics Association in 1967 and caught the attention of Shōji Yamagishi, editor of Camera Mainichi. Yamagishi was intrigued and published these early experiments, which ultimately led to Moriyama’s first book, Nippon gekijo shashincho (Japan: A Photo Theater – Bookshop M., 1968).

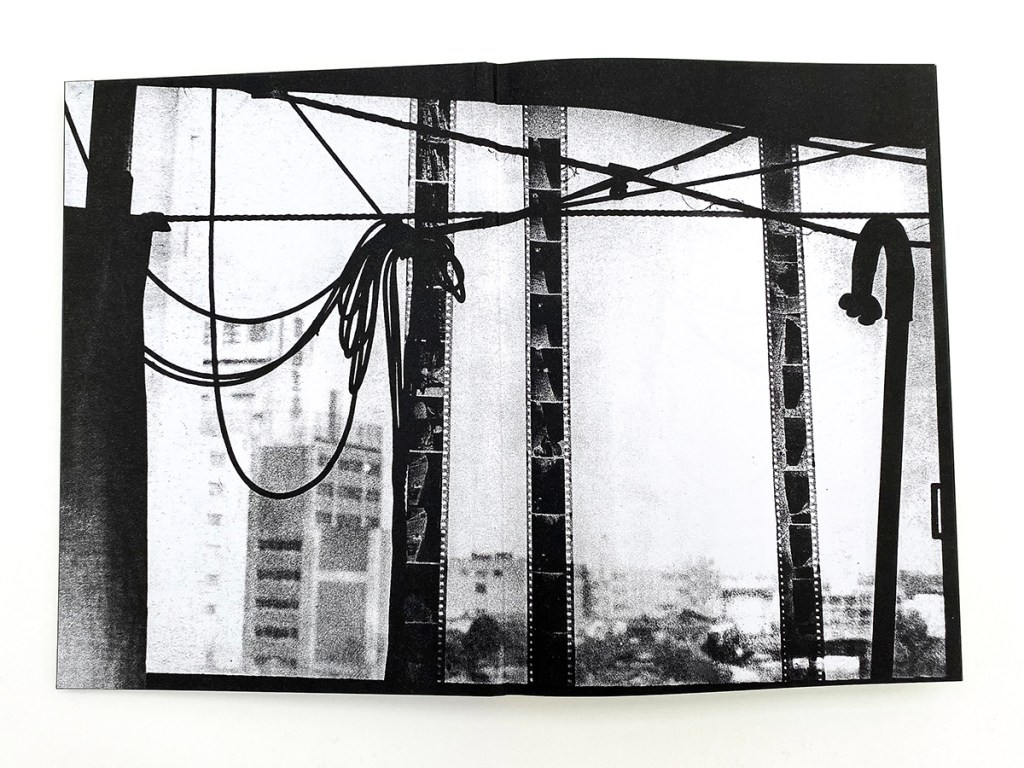

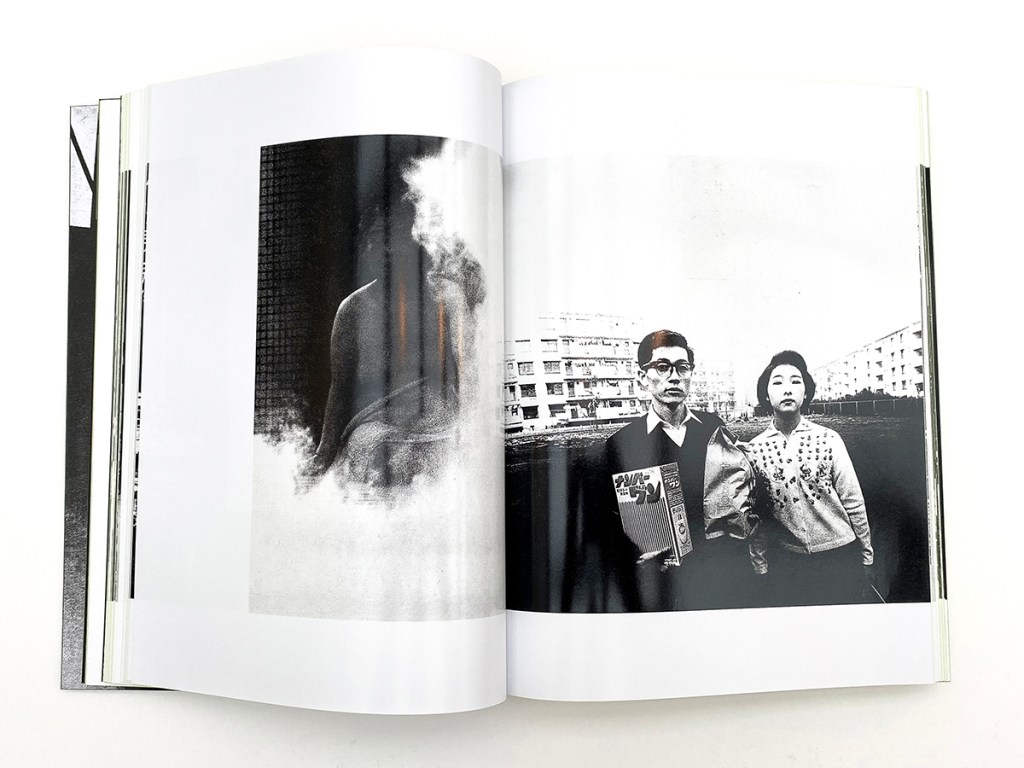

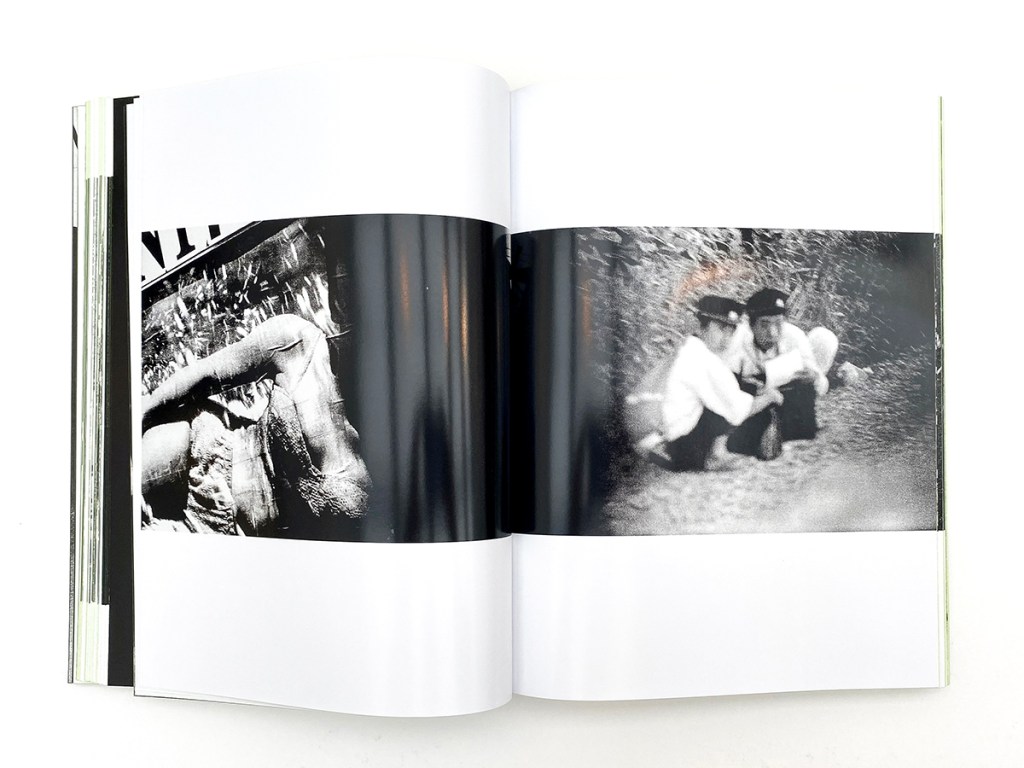

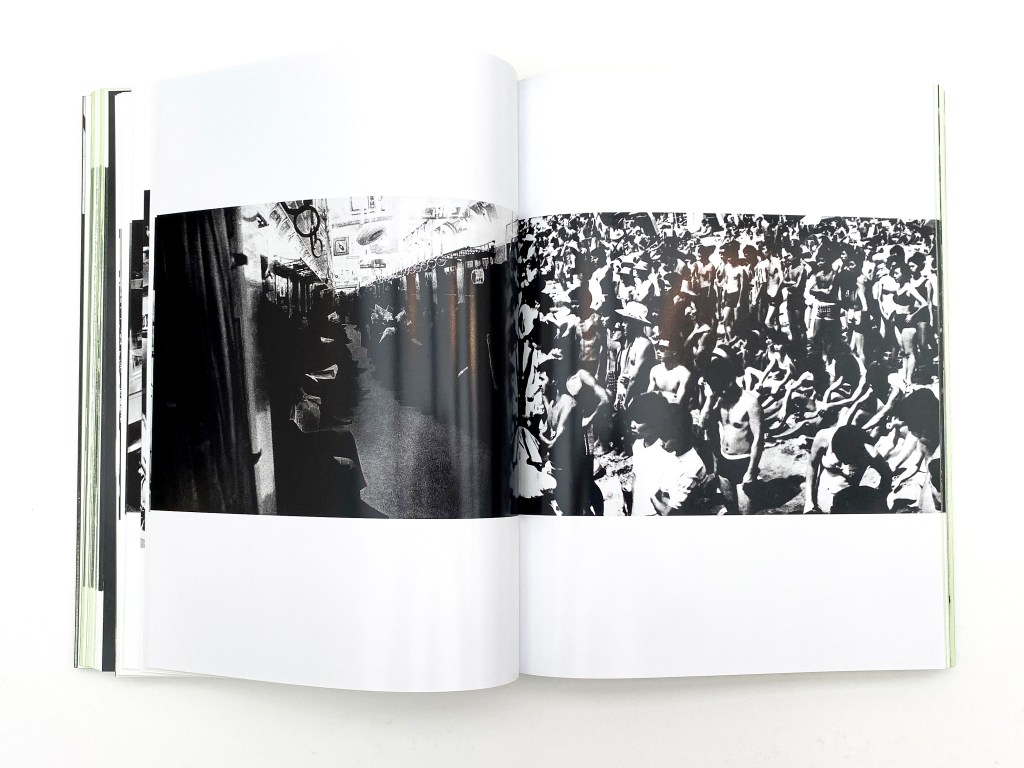

Japan: A Photo Theater garnered tremendous attention and praise – photographers like Shomei Tomatsu (one of Moriyama’s heroes), Takuma Nakahira, and Nobuyoshi Araki. A Photo Theater juxtaposes pictures of traditional Japanese theater (both on and off stage – and clearly showing the influence of Hosoe) with gritty street scenes in Tokyo and Shinjuku. This combination provided a compelling illustration of post-war Japan – the complex transition from a constitutional monarchy to an industrialized, democratic nation. Throughout these pictures, Moriyama introduced the hard-edge style that has defined his work for decades – grainy, high contrast images sharpened to a point.

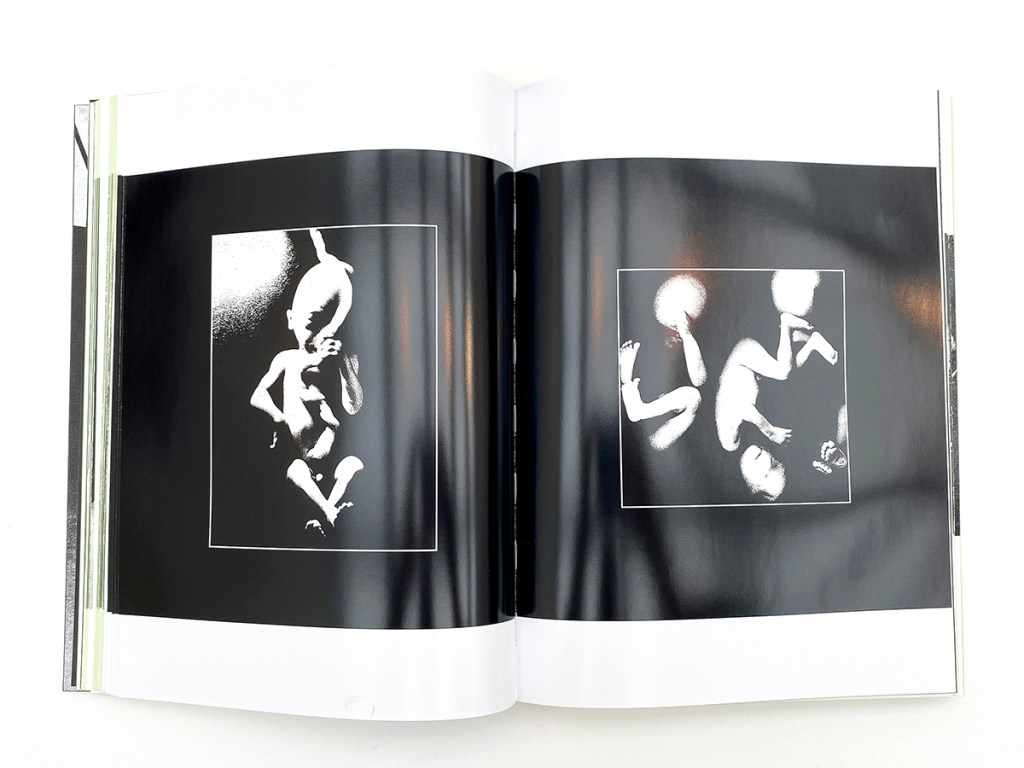

In addressing his strategies for Japan: A Photo Theater, Moriyama said, “It was meant as an experiment. I wondered, if I were to remove each of the photographs I had taken over the previous few years from their original context, treating them as fragments in a completely different context and making each equally flat, would I be able to reconstruct the confusing views that exist in daily life?” (Moriyama, “Unexpected Encounters – 1960s,” as cited by Mark Holborn in “A Performance.”). The end of the book truly illustrates this experiment; the last 8 pictures are completely unlike all the others, printed on glossy, black pages, the end of the book shows specimen jars Moriyama chanced upon, each showing a silhouette of a human fetus floating in space. When asked about these, the photographer said these bodies moved him deeply, as if in an instant he had a deeper feeling for humanity. The fetuses are also the perfect metaphor for Moriyama’s greater narrative about post-war Japan, representing both the past and the future; suspended in formaldehyde, the dead babies represent traditional Japanese culture, destroyed and reborn in the atomic age.

Japan: A Photo Theater has been reprinted numerous times, most recently in a new compendium published by Thames & Hudson and Getty Publications, Quartet. Like the title suggests, this new publication reproduces more than just A Photo Theater and shares his first four books – including Nippon gekijo shashincho Karyudo (A Hunter), Shasin yo sayonara (Farewell Photography), and Hikari to Kage (Light and Shadow). Quartet is a handsomely produced book, each page lavishly printed with rich inks and varnishes, the bound volume housed in a sturdy slipcase. The four books are reprinted in entirety, and accompanied by essays from Mark Holborn, Tadanori Yokoo, and Moriyama. Presented this way, Quartet highlights the early, formative years of Moriyama, arguably one of the most influential and iconic photographers to emerge in the 20th century.

I’ve often thought of Moriyama’s early work as the stuff of legend. I’ve known of his work for years, largely by reading general surveys of Japanese photography, but feel I first really learned about Moriyama’s books in the great series by Gerry Badger and Martin Parr, The Photobook: A History. Just reading about his early books got me excited; they sounded revolutionary, groundbreaking, and punk rock, further stimulating my imagination and thirst for photography. In his earliest years, Moriyama set an entirely new precedent for understanding the medium, exploring a gritty, alienated vision of post-war Japan that referenced a diverse array of artists – Hosoe, William Klein, Robert Frank, and Andy Warhol. His use of materials offered previously unimagined vocabularies, proving that photography can evoke profound mental and emotional experiences while still describing the physical world.

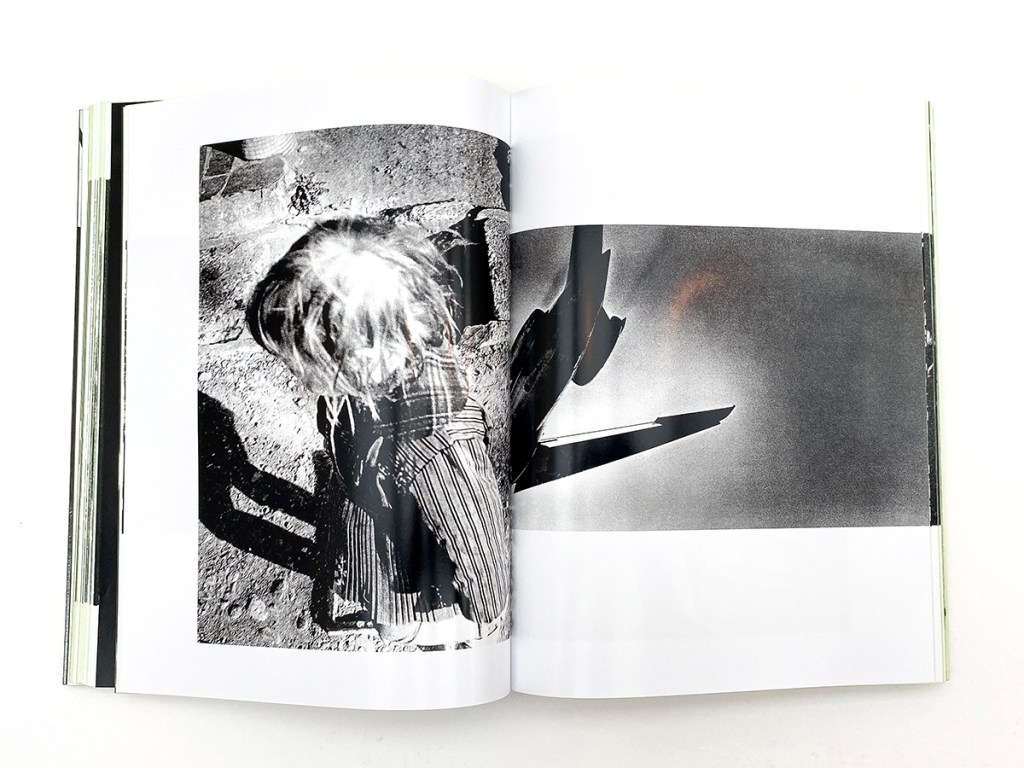

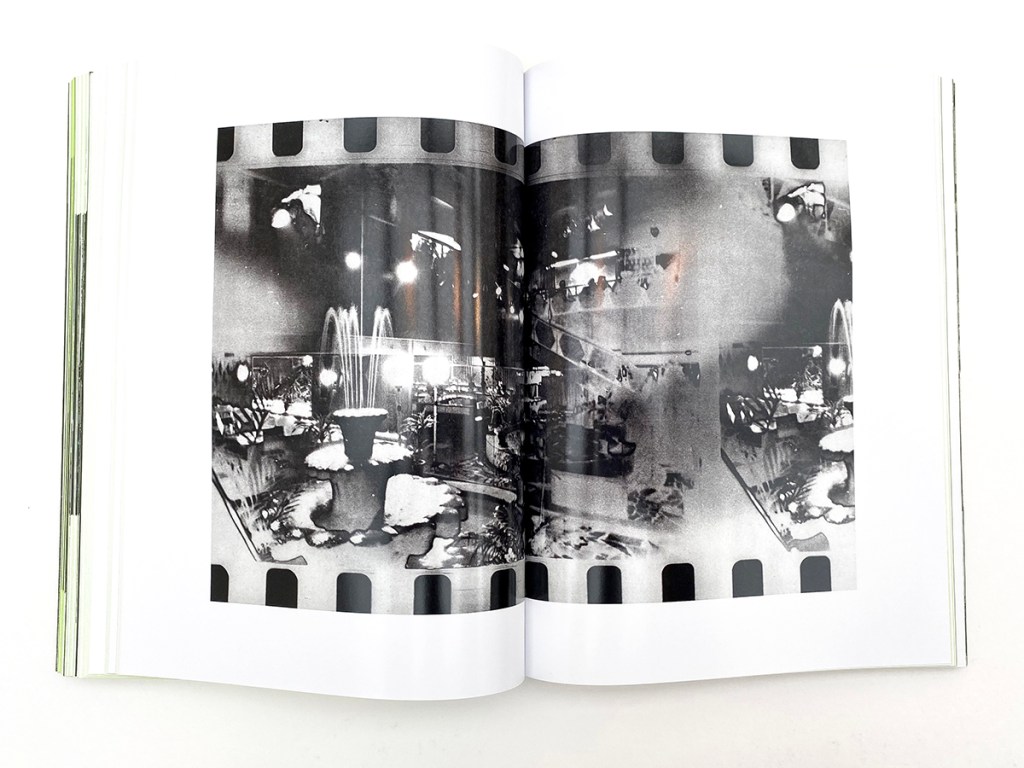

Looking at these early works sequentially, it’s easy to understand that with each publication Moriyama pushed the medium harder and farther than he did with his previous book. A Hunter is even looser than A Photo Theater, not anchored between classical theater and the streets, and feels like a more purely stream-of-conscious narrative, incorporating every kind of street scene with images he found, rephotographed images discovered on television screens, billboards, and in newspapers. Within the pages of A Hunter, we see young men in the swim trunks enjoying the beach and netted octopuses laid out in the sun; Bridget Bardot and knockoff Rolexes; bikers that look something like ghosts, blasted by a flash at 2 in the morning; a day at the beach that reminds me of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle; the deep abyss of his lover’s pubes and strip clubs clouded with smoke and whiskey; and the single image most associated with Moriyama, Stray Dog. The combined effect is equally alienating and freeing; armed with a shotgun loaded with Tri-x, Moriyama is a hunter searching for a liberated self in a landscape of ruin, looking for a truth in a nation pointed in the direction of “democracy and freedom,” but openly being consumed by capitalism and excess.

Of the four books in Quartet, I am most familiar with Farewell Photography. I have a copy published by Power Shovel in 2006, designed and produced to deteriorate with each viewing, and it’s one of those I covet most in my collection. Indeed, I consider this one of the best and most revolutionary photobooks ever published. I still think of Badger’s and Parr’s comments about it:

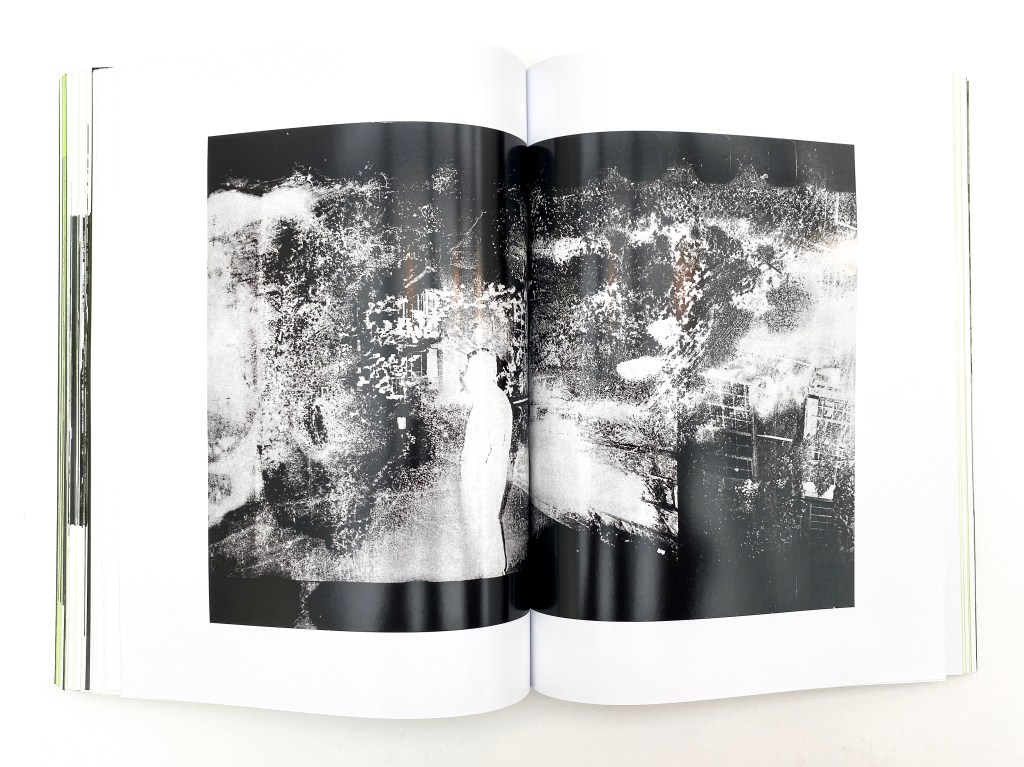

“Shashin yo Sayonara (Bye Bye Photography) is … one of the most extreme photobooks ever published. Daido Moriyama pushes both the form of the photographic sequence and the photograph itself to the limits of legibility, with a barrage of stream-of-consciousness imagery culled from his own pictures, found photographs – such as shots of car accidents – and images taken from the television set…The photographic language is one of blur, motion, scratches, light leaks, dust, graininess, and stains, like Robert Frank or William Klein on speed.”

I love the description, Robert Frank or William Klein on speed, because this does indeed accurately explain the feel of the pictures. There is a bit of overlap with the first two books – many of the pictures coming from the same rolls of film – but in Farewell Photography Moriyama discarded all good graces and any reverence for technique. These photographs were printed with deep scratches, or clumsily (drunkenly?) crammed into the enlarger to create rude, unintentional croppings. In creating a true chronology of Moriyama’s work, there is some confusion about Hunter and Farewell Photography. Both were released in 1972, and technically latter was released first, but Moriyama did make and sequence the pictures in Hunter earlier.

It probably isn’t wrong to assume whiskey and speed influenced Farewell Photography because it was another ten years before Moriyama made another book; the essays in Quartet make it clear, this was a result of his falling heavily into addiction. It all started when a friend gave him some pills, a seemingly simple thing that made a tremendous impact on Moriyama (perhaps somewhat like his discovery of the specimen jars). Without going into too much detail, he is candid about the impacts of his addiction, saying he spent the next ten years feeding his habits and keeping photography to the peripheries.

In 1982, Moriyama released his fourth book, Hikari to Kage (Light and Shadow). This book is much cleaner; still made with the same gritty, high-contrast style but also much more polished. In some ways, Light and Shadow feels like the most mature of those included in Quartet, but perhaps also the least interesting. I believe at his best, Daido Moriyama is a genius, a true modernist master of post-World War II Japan, able to chart his nation’s history through his personal diaries, creating an uncompromising vision of anger, hunger, and freedom. At other times, Moriyama feels like a Photoshop filter before Photoshop. There are times when his technical approach feels more like effect, more swagger than a rebellion. There is no denying the pictures in Light and Shadow are beautiful, dissonant and yet somehow still sumptuous, but they also look like pictures I know too well – whether from so many other books by Moriyama himself, or because of a style and feel reminiscent of photographers like Ralph Gibson or Jean Loup Sieff. With his first three books, Moriyama was a revolutionary; in Light and Shadow, he reemerges as a more tempered and mature artist. Moriyama did go on to make many more fantastic books, but Light and Shadow feels exactly like what it is, the artist trying to get back on his feet again.

Quartet reveals the evolution of one of the most influential voices in photography, a true revolutionary that helped reshape the medium in the post-war era. Through his raw, unflinching style and experimental approach, Moriyama created a new visual language that captured the disorientation and radical transformations of Japanese society while simultaneously pushing the boundaries of photography. From the cultural tensions documented in Japan: A Photo Theater to the deliberate deconstruction of photographic conventions in Farewell Photography, these early works established Moriyama as more than just a photographer documenting a changing nation – he became a vital interpreter of modernity itself by create richly visualized diaries of a life in transition. His influence continues to resonate today, a reminder that photography is a powerful tool of documentation that can also give visible form to the psychological and emotional experiences of a rapidly changing world.

Contributing Editor Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

PhotoBook Journal has previously reviewed Daido Moriyama’s Record and Record 2.

____________

Daido Moriyama – Quartet

Photographer: Daido Moriyama

Editor: Mark Holborn

Publisher: Getty Publications (USA), Thames & Hudson (UK) 2025

Essays: Mark Holborn, Tadanori Yokoo, and Daido Moriyama

Designer: Jesse Holborn

Hardcover in slipcase; 440 pages; 8 5/8 x 11 5/8 inches (22 x 29.5 cm); 250 black and white illustrations; ISBN: 9788887120096

____________

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s).

Leave a comment