Review by Brian Arnold ·

Canyon del Diablo – Devil’s Canyon. Not a unique name, I know, but to me it’s iconic. In the spring of 1995, not long after I submitted my undergraduate thesis on the anthropological writings of Zora Neale Hurston, I traveled to the desert lands along the Colorado/Utah border with my brother and a close mutual friend. Together we decided to hike deep into its red rock canyons. Devil’s Canyon wasn’t our original goal, but when we arrived at the Canyonlands National Park, the ranger turned us away. Apparently, they’d implemented a new reservation system, and we needed to confirm our trip months in advance. The ranger was helpful, though, and guided us to some Bureau of Land Management zones not far away – it was possible for anyone to camp on these lands anytime, no reservations needed.

We turned the car around at the park’s entrance, stopped for some pizza and beer, and drove for another 40 minutes on remote dirt road before parking our car at the top of another gated trail, marked as BLM lands (think of some of those scenes from Breaking Bad). We brushed our teeth using some of the little water we had, laid our sleeping bags next to the car and bedded down under the stars (the view was breathtaking). The next morning, we made some coffee, repacked our gear, and then spent the next eight hours hiking to the bottom of the canyon. It was brutal under the relentless desert heat, but we had to make it to the bottom of Devil’s Canyon, such a long hike under harsh southwestern sun, because we only had a gallon of water between the three of us. There were some natural subterranean streams down at the bottom where we could find water, but nothing between our car and the final descent.

The journey was tough but magical. We were awed by the harsh rock walls of the desert canyon, sculpted over millions of years, assembled with jagged red rock with just enough tough, green grasses to provide a little color contrast. This was ancestral Pueblo land, and we did see traces of ancient civilizations. Indeed, at the bottom we found not only water, but incredible artefacts, petroglyphs carved into the canyon explaining a life known thousands of years ago. The towering red rock on the canyon were equal parts threatening and gorgeous, and like these petroglyphs, represented an understanding of time we could feel but not comprehend. We pitched our tent near the stream, a current that emerged from an underground rock basin and created a beautiful waterfall 50 yards from our tent, a current we used for both drinking and bathing. We spent our days wandering the base of the canyon, finding ancient pictures carved into stone, snakes and spiders, and incredible, humbling views. I brought a William Carlos Williams book, and we would spend our evenings sitting on a rocky bluff, looking at a horizon that appeared infinite, and taking turns reading poems aloud. I felt like we discovered a new kind of consciousness – something very different from our lives in Denver – a way of thinking and being dictated by the desert, offering us important lessons about time, place, and our own, small position in the universe.

I grew up in the Southwest and consider it a major part of my identity. My parents collected Native pottery and textiles, used to decorate our walls, placed on shelves next to books by Alfonso Ortiz and Maya Angelou. My stepdad encouraged me to read The Teachings of Don Juan by Carlos Castenada and even bought me my first shamanic drum (as a teen I explored alternative approaches to consciousness and spirituality). I hungrily read the first three of Castenda’s books, not caring about the dubious anthropology and whole-heartedly embracing its core vision about becoming a spiritual warrior. One of my favorites of the shaman’s philosophies was his idea about place, that spaces and landscapes we occupy reflect a piece of the cosmic consciousness. Part of your goal as a true warrior is to learn to connect with the consciousness of a place, to accept your role as a smaller piece of a greater experience. If you are open enough, your consciousness will become a reflection – or perhaps a conduit – of the space and thus proving a previously unimaginable link to the universe, especially in the harsh deserts along the borders of Texas and New Mexico.

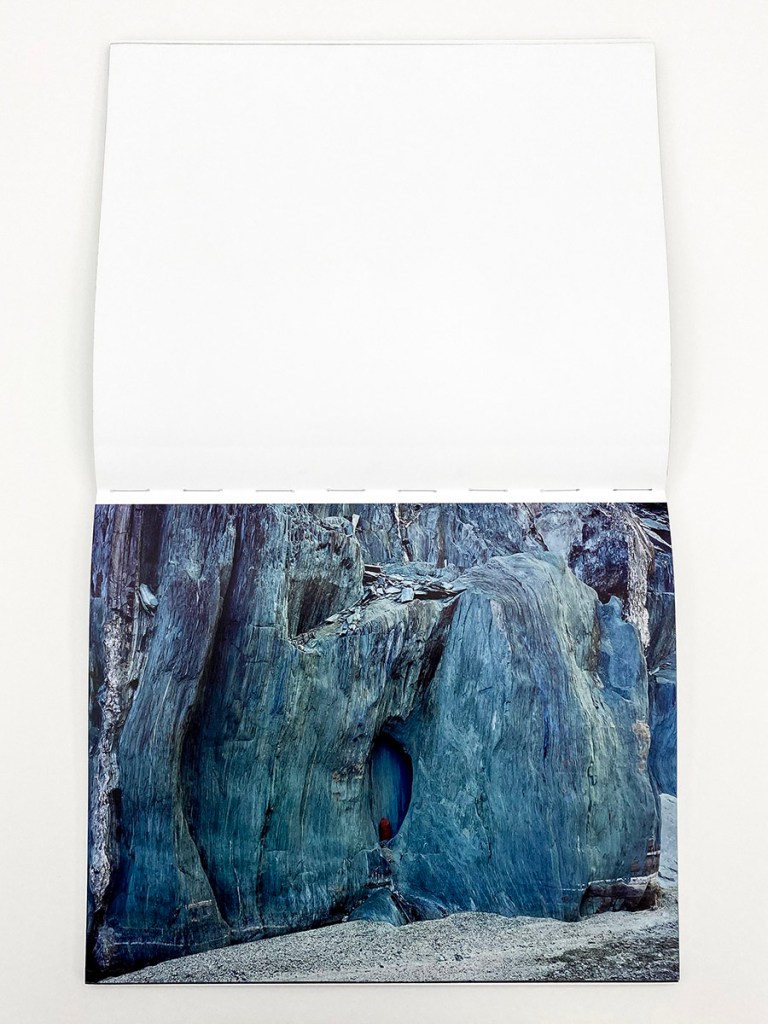

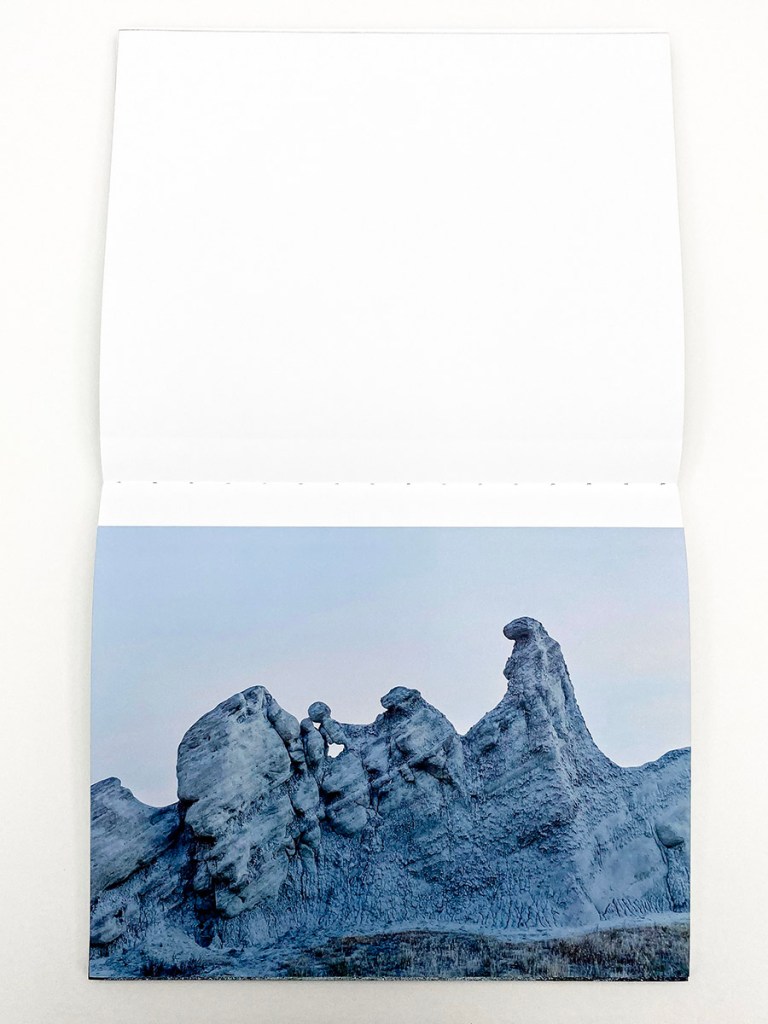

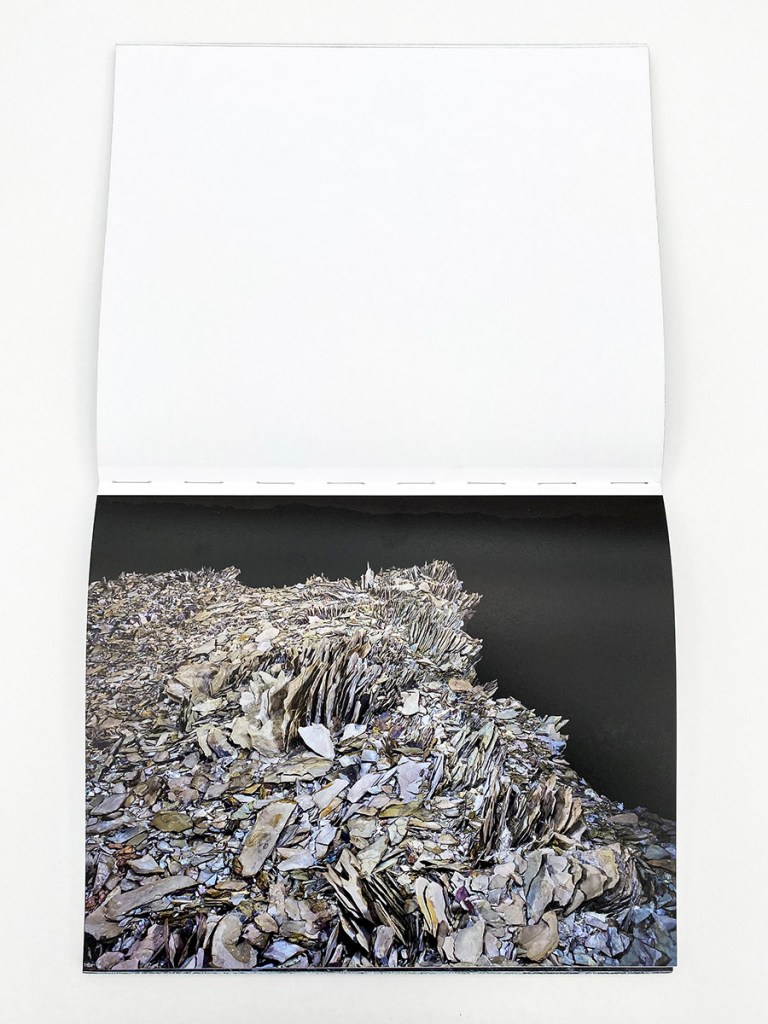

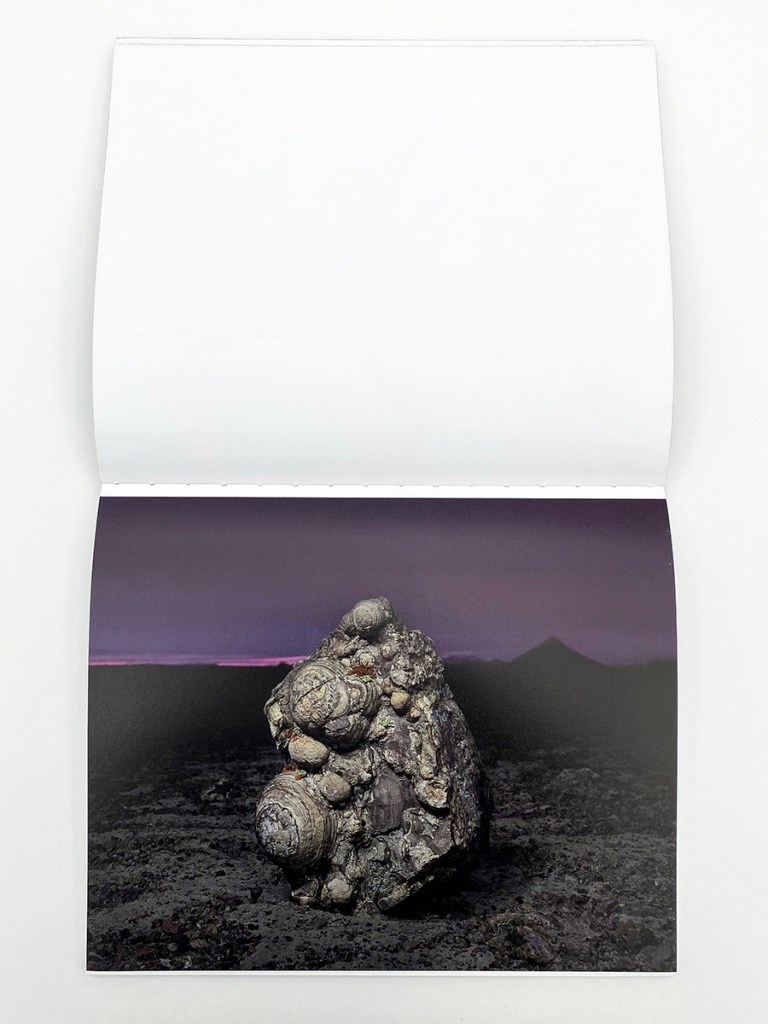

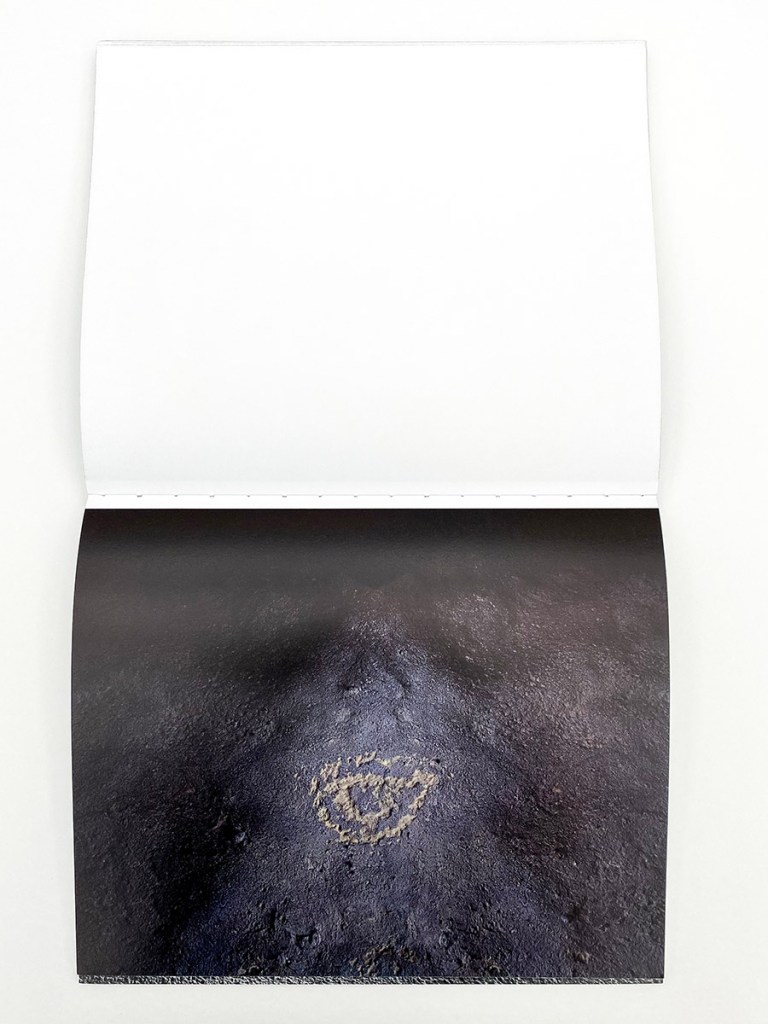

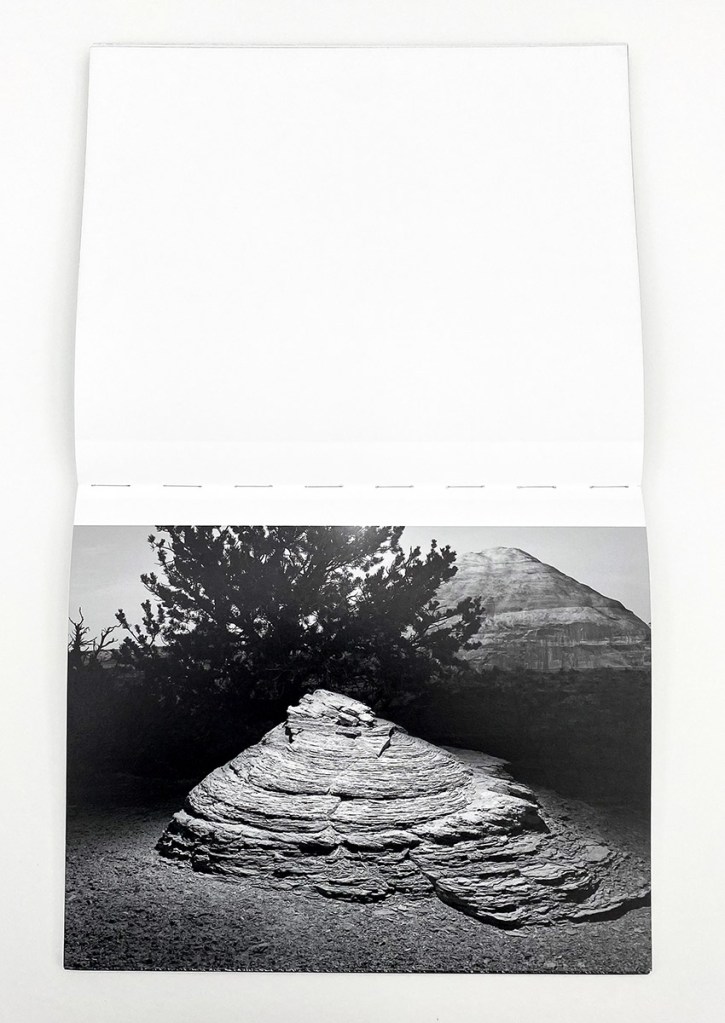

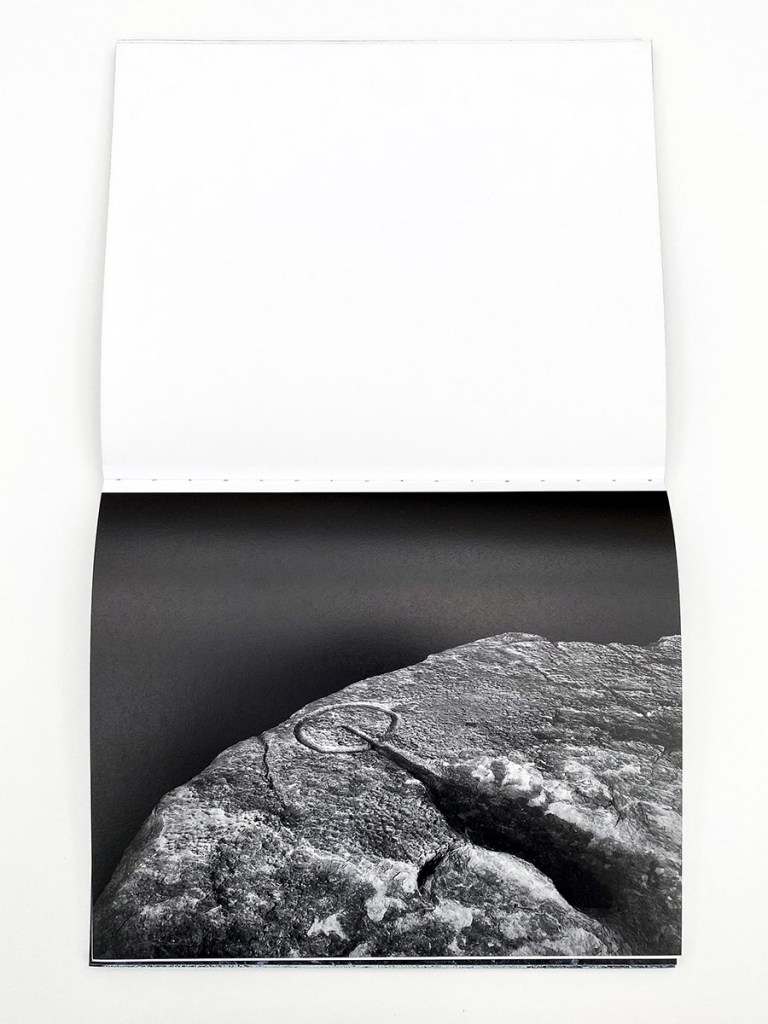

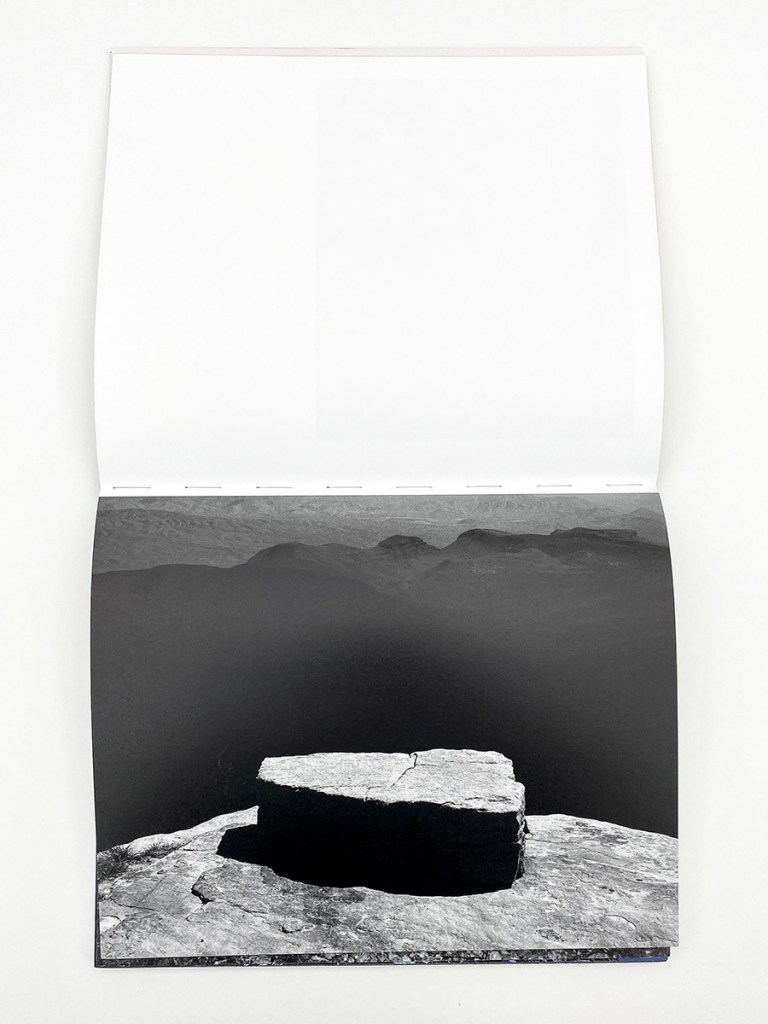

I find all this – the petroglyphs, Don Juan, awe-inspiring views of the star, hikes under the brutal desert sun, and a stark awareness about the distinctions between human and geological time – as the perfect entry point for understanding the remarkable and enigmatic photographs in Glass Mountain, the new book of landscape photographs by Michael Lundgren published by Stanley/Barker. It is an exploration of some of the deepest mysteries we know, depicted in the unlikeliest forms and materials – western wastelands, tidal pools, crooked cacti, an abandoned well, and shards of opal, each pointing the viewer towards histories and experiences much greater than our own. The design and production of the book offer a tremendous vehicle for explaining Lundgren’s essential ideas. Like the petroglyph’s found at the bottom of Devil’s Canyon, the cover is etched with small silver circles, spelling out the photographer’s name and book title but also functioning as a primitive map of the stars. Opening the book feels reminiscent of a psychedelic experience, the binding finished in a reflective paint that shines mesmerizing glimpses of rainbows when held to the light just right.

To really engage Glass Mountain, I went back and revisited Lundgren’s first books with Radius Books, Transfigurations (2008) and Matter (2016). The first offers a more traditional approach to landscape, composed of lush black and white prints of the southwest, presenting an understanding of landscape that is as beautiful as it is familiar. The pictures in Transfigurations hint at something more metaphysical, it is a very ambitious book (introduction by Rebecca Solnit), but in the end these just feel like hints. Matter picks up here, boldly venturing into something much more abstract. It’s a book that strives to articulate more mystical understanding of landscape by deeply exploring microscopic views of geology and the elements, an effort to discover macroscopic experiences in the harsh realities of earth (a particularly poignant picture shows an animal skeleton decaying in some kind of mineral sludge bath). Ultimately, the pictures utilize only one compositional strategy (object clearly in the middle of the frame) and the photographic space flattened by the photographer’s use of flash. This does result in many interesting pictures, but it also feels blunt and rigid at times.

After publishing Matter Lundgren had a child; the inevitable maturity this brought to his life is evident in the newest book (think of the wisdom and mastery found in Emmet Gowin’s landscapes, an obvious influence on Lundgren). Glass House is much more nuanced, stylistically speaking, than Transfigurations, and less blunt than Matter, resulting in pictures created with a fully formed philosophy about landscape and in a visual language unique to the photographer. In these photographs, the use of flash feels much more controlled and nuanced – the expression of color in many of these pictures is astonishing – and the photographer employs both close-up, microcosmic perspectives juxtaposed with larger views of the landscape, resulting in book that feels much more fluid and complete.

When I first discovered Glass Mountain, I immediately thought about some of my most profound experiences in landscapes. After discovering it, I took a major road trip to the American Southwest, a region I hadn’t visited for a decade. We flew to Denver before traveling southwest through Colorado and into New Mexico – through Beuno Vista and Crestone, the Sangre de Christos, and Bandelier National Monument, and later exploring the arts scenes in Taos and Santa Fe. With these travels, I found so many opportunities to reflect on my experience of the landscape – the primitive stoneware tea set we bought in Taos, the Anges Martin Gallery at the Harwood (the perfect expression of desert light!), and the hours spent driving along infinite vistas speckled with red dirt and tough grasses and sage. Returning home to New York, I opened Glass Mountain and again felt this deep resonance with both the places and pictures, finding mysterious and compelling photographs page after page. Lundgren, a true devotee of rigorous photographic pursuit, also reminded me that deep commitments to the simple photographic attributes of place and light can still result in pictures of endless complexity.

Contributing Editor Brian Arnold is a writer, photographer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY.

PhotoBook Journal previously reviewed Michael Lundgren’s books Matter and Transfigurations.

____________

Michael Lundgren: Glass Mountain

Photographer: Michael Lundgren

Publisher: Stanley/Barker

Language: English

Design: Sheret

Hardcover with gilded edges; 120 pages; 9.5 x 12 inches (24 x 30 cm); ISBN 978-1-913288-78-5

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment