Review by Rudy Vega ·

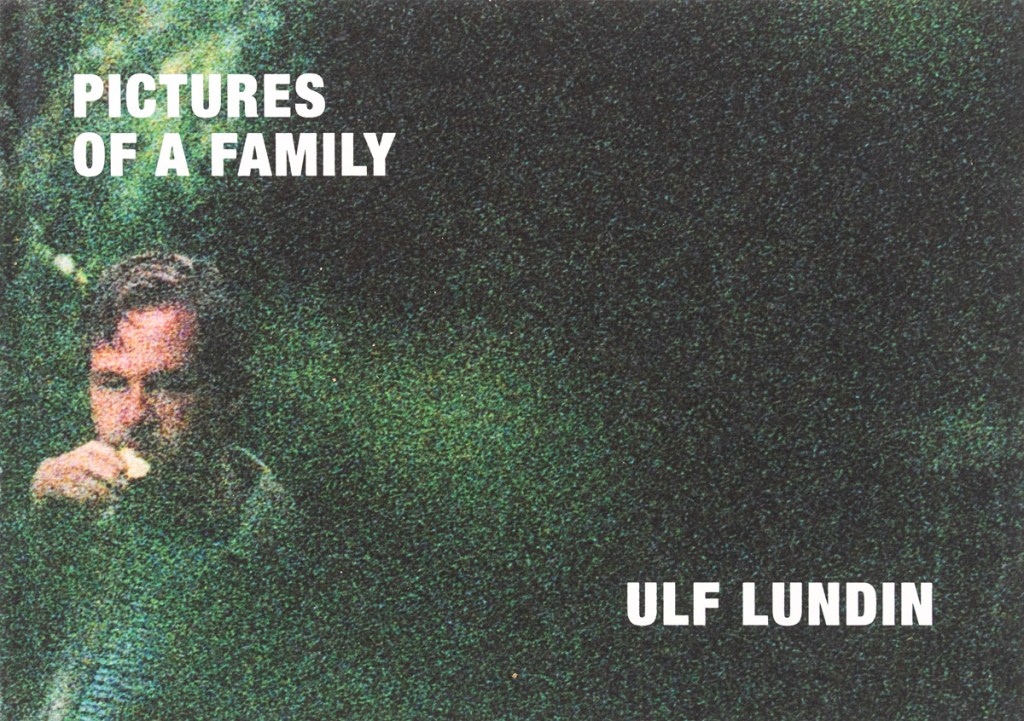

Ulf Lundin’s Pictures of a Family first premiered as an exhibition in 1997. Fast forward to 2024, and Pictures of a Family is realized as a photo book. Consisting of 124 pages, of which 66 are photographs (64 color and 2 black and white), it’s an interesting look at photography that goes beyond what the title suggests.

In his foreword, Lundin writes about a relationship with a childhood friend and their subsequent paths to adulthood. In it, he expresses admiration, longing, and envy while questioning the choices he made leading up to his current station in life.

An excerpt from his introduction reveals his thought process: “And now, here I sit again, looking at my reflection in the mirror of this family. Am I living the life I want to live, or do I want something different? Have I even made a conscious choice? Could I choose something else, or is it too late?”

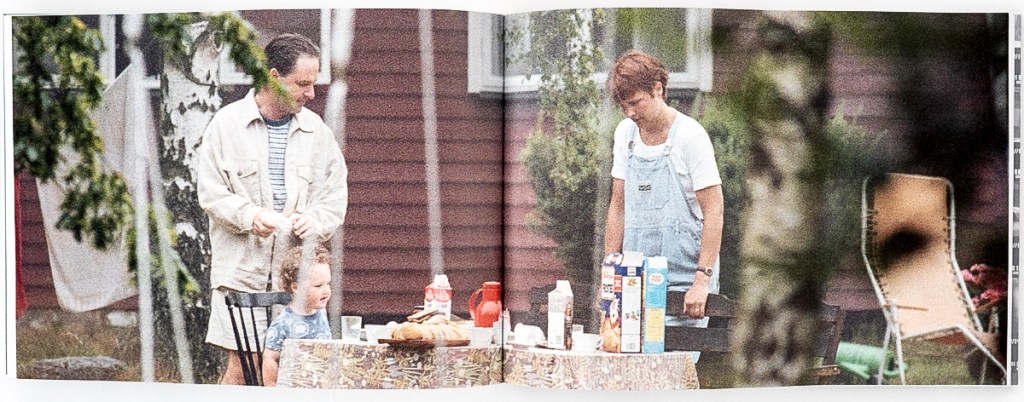

This quote encapsulates his motivations behind Pictures of a Family. Lundin adds: “He still lives in the town where we grew up and now he has a wife, two sons, a home in a terraced house and a steady job. The security of his life appalls and attracts me at the same time. It is difficult to put a finger on the choices which have determined our present lives. I have spied on him and his family for a year now and secretly photographed them. There are over a hundred rolls of film in my archives. We have made a contract in which they have given me permission to spy on them. In other words, they know that I’m there but they don’t know when.”

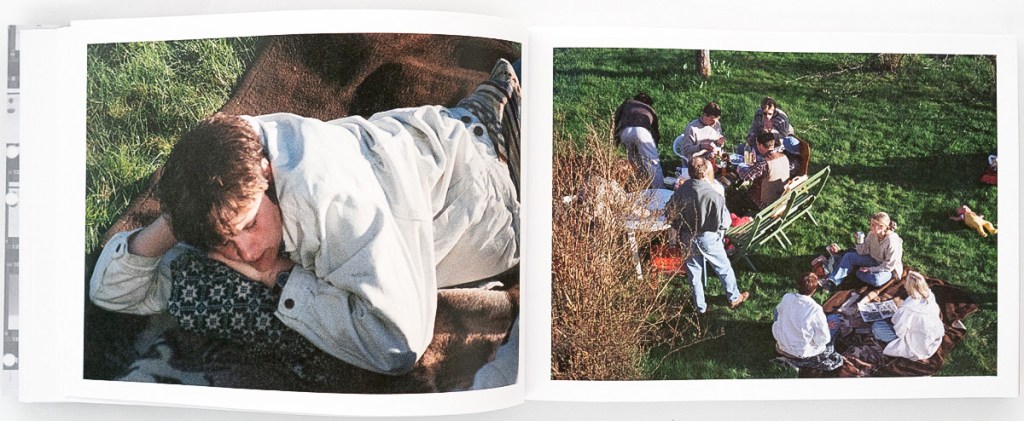

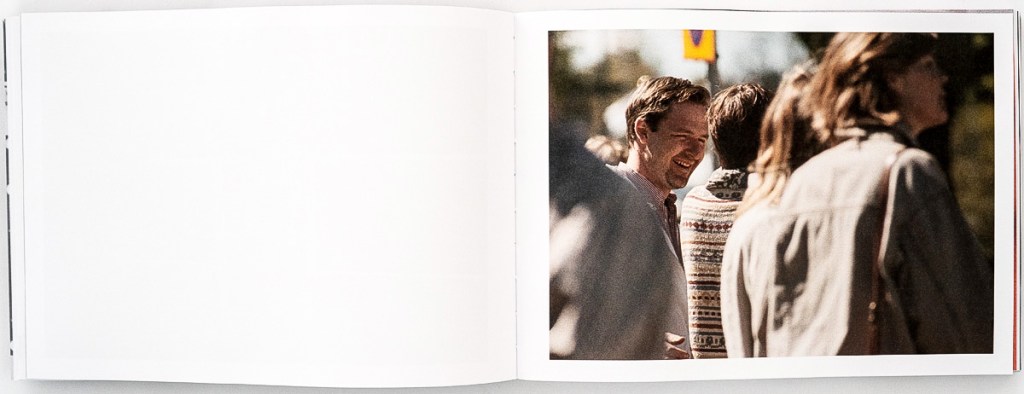

Pictures of a Family is at once personal and universal. While functioning as a narrative seeking possible self-enlightenment, it also serves to bring the focus squarely on the act of photographing people in the manner he has chosen. Lundin’s aesthetic choices—shooting between branches with a long telephoto lens and employing tight framing—emphasize the voyeuristic nature of the project. The resulting images incline the viewer to read the subjects as self-conscious, though this interpretation may reflect more about our own biases than the subjects themselves. Lundin’s project exemplifies the tension between personal intimacy and the public nature of photography, a recurring theme in contemporary art. The project interrogates the ethical boundaries of observation, echoing debates in both art and cinema about the role of the observer.

By positioning the camera and, by extension, himself as a voyeur, Lundin raises important questions about the ethics of capturing others in intimate, private moments. The tightly framed photographs, often fragmented and shot from concealed vantage points, resemble surveillance or voyeuristic documents more than traditional family photos. These images also reflect fragments of Lundin’s personal desires, further complicating the narrative of observation. The negotiated consent—with the family’s agreement to be photographed without knowing when—recalls Michel Foucault’s notion of the Panopticon: visibility as a form of control. This dynamic of consent and secrecy places the audience in an uneasy position, complicit in the act of looking.

Lundin’s approach resonates with the works of Sophie Calle and Shizuka Yokomizo, who similarly navigate the boundaries of consent and observation. Like Calle’s Suite Vénitienne, Pictures of a Family explores the ethical tension inherent in photographing others as a means of self-discovery. Yokomizo’s Dear Stranger, where participants consent to be photographed without knowing the precise moment, provides another apt parallel.

The personal nature of Pictures of a Family reflects broader cultural concerns about voyeurism, trust, and identity. The aesthetic—intensely surveillant and fragmented—invites viewers to consider the tension between the subjects’ apparent self-consciousness and the artist’s own perspective. Lundin’s choices force us to confront how deeply the act of looking is tied to personal interpretation and desire. Lundin’s introspective narrative provides a lens through which the audience can reflect on their own lives. The juxtaposition of his friend’s “secure” life with his own more uncertain path transforms the project into a meditation on envy, admiration, and the choices that shape us.

Cinematic parallels also deepen the understanding of Lundin’s work. Films like Mark Romanek’s One Hour Photo and Jocelyn Moorhouse’s Proof explore the act of observing others as a surrogate for unmet emotional needs. In One Hour Photo, the protagonist’s obsessive attachment to a family through their photographs mirrors Lundin’s long-term observation, blending admiration with discomfort. Similarly, Proof interrogates the power dynamics of photography, where trust and interpretation become central themes.

By transforming Pictures of a Family into a book, Lundin shifts its focus from a private act of observation to a public dialogue about the nature of voyeurism. This reframing diffuses some of the inherent ethical critique by inviting viewers to grapple with their own role as spectators. The act of making this project public compels us to confront our fascination with the lives of others and consider whether photography can ever truly be neutral.

In the end, Pictures of a Family functions as both a deeply personal self-examination and a universal critique of the ethics and aesthetics of observation. Lundin’s project forces us to question the power dynamics inherent in photography and the complicated relationships between the observer and the observed.

________

Rudy Vega is a Contributing Editor and resides in Irvine, Ca. He is a fine art photographer and writer.

________

Ulf Lundin – Pictures of a Family

Photographer: Ulf Lundin, Lives and works in Stockholm, Sweden (born in Alingsås, Sweden).

Publisher: Skreid Publishing, Sweden © 2024

Essays: Ulf Lundin

Language: English, Swedish

Clothbound Hardcover book, Livonia print 124 pages, 64 color images. 7”x10” inches; ISBN 978-91-639-9030-4

Editor: Ulf Lundin, August Eriksson

Book Design: Ulf Lundin, Magnus Karlsson

____________

____________

Articles and photographs published in the PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff and the photographer(s). All images, texts, and designs are under copyright by the authors and publishers.

Leave a comment