Review by Steve Harp •

…pictures have an uncanny ability of suggesting that there is another world…They represent a sense of otherness. The figures in photographs have been muted, and they stare out at you as if they are asking for a chance to say something. – W.G. Sebald

The concept of the “uncanny,” which Sigmund Freud investigates in his 1919 essay of the same name, can, at its simplest, be described as that which is seemingly most familiar yet, upon closer consideration, is revealed as actually the most unfamiliar. The example Freud gives and structures the first third of his essay around is the concept of home and the homely (heimlich). Tracing various definitions and uses of the term heimlich, he concludes this opening section by stating:

Thus, heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich.

In other words, in order to experience something as uncanny, it must be simultaneously familiar, “homelike,” yet at the same time unfamiliar and unsettlingly strange. The term “uncanny” is one of a litany of words which in general usage, often bear only a fleeting or tangential connection to the original concept or meaning (see: surreal)…

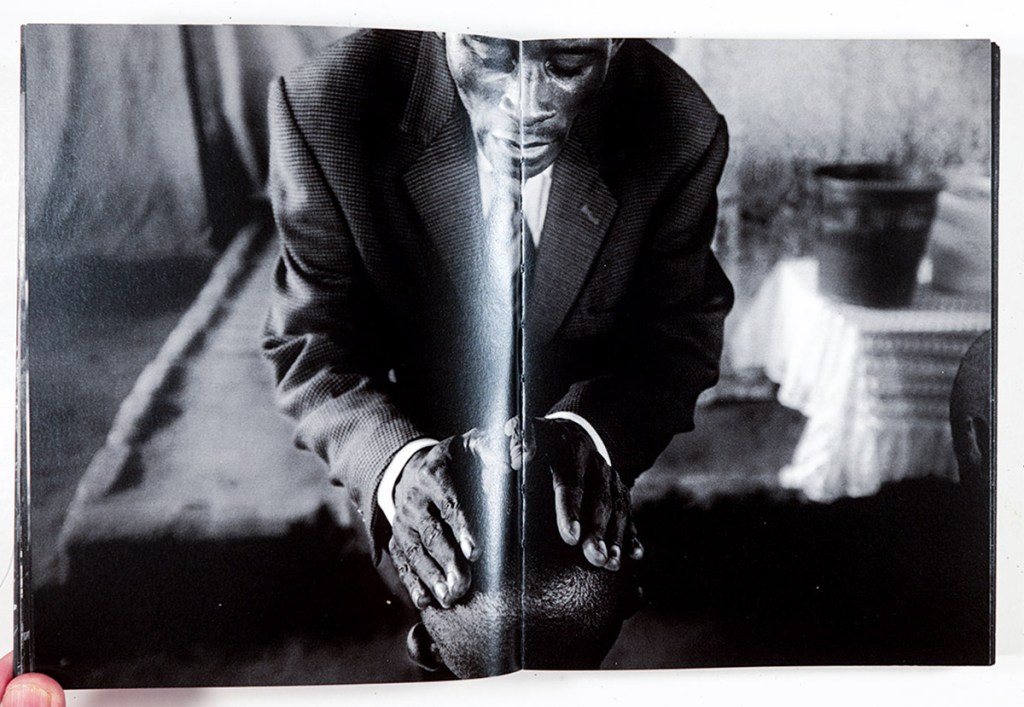

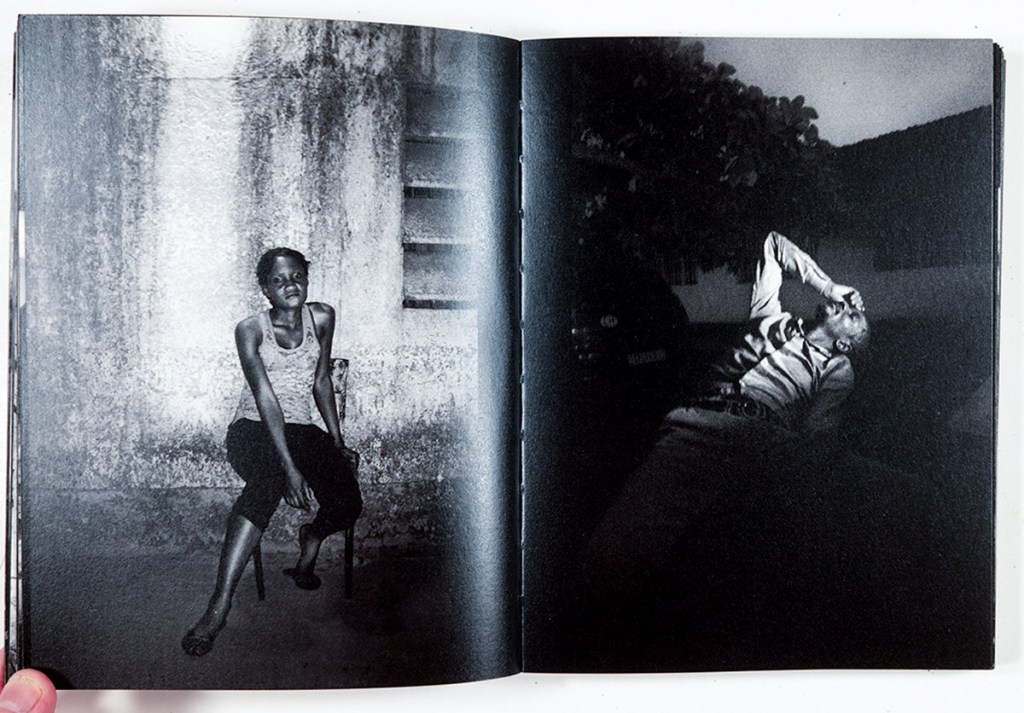

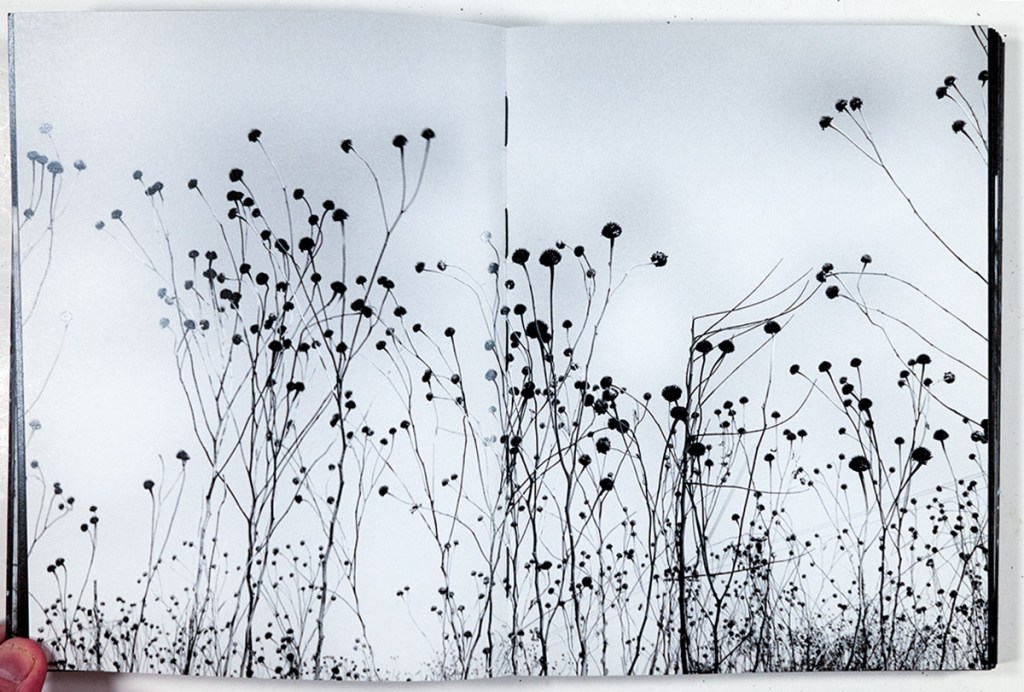

So it was with great interest that I began my encounter with Leonard Pongo’s 2023 monograph, The Uncanny. My review copy is a softcover, 6.5” x 8.5.” The wrap-around cover depicts what looks to be a field of weeds against a night sky. We don’t see the ground the weeds spring from. In fact, the plants themselves don’t seem to be illuminated so much as…strangely glistening or shimmering silver objects. The only text, along the spine, is also in silver. Opening the book, the front and back cover flaps extend the mysterious field into a true panorama, 24” x 8.5.” Moving into the book, we’re initially confronted by four photographs of black Africans, residents of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (these specifics we learn only later) before the title page, which is white text on black background.

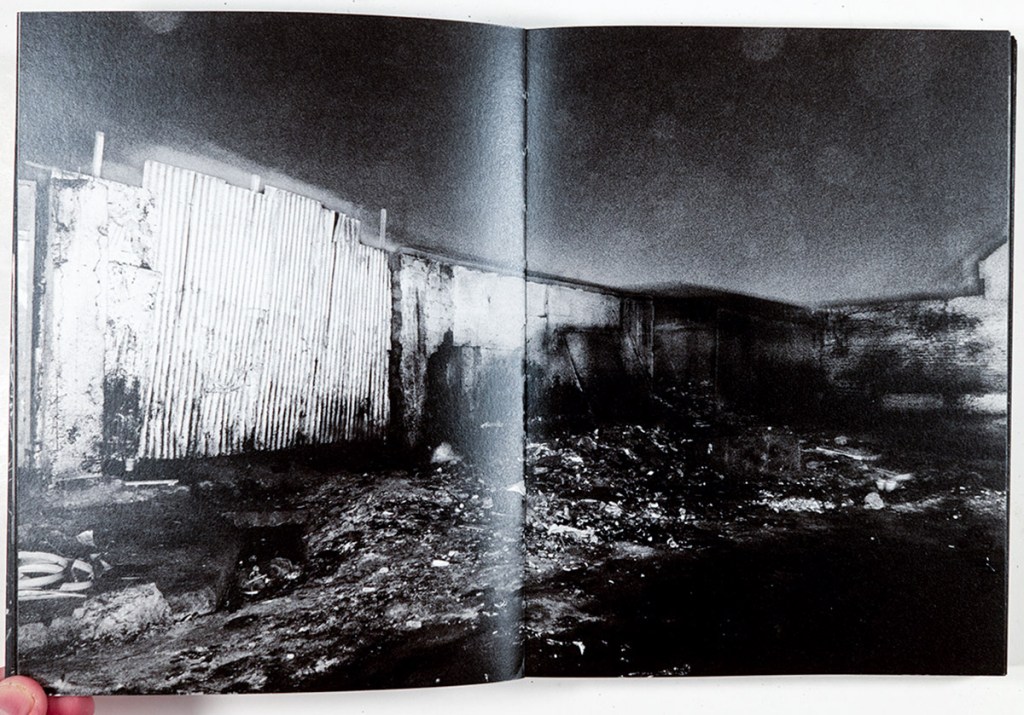

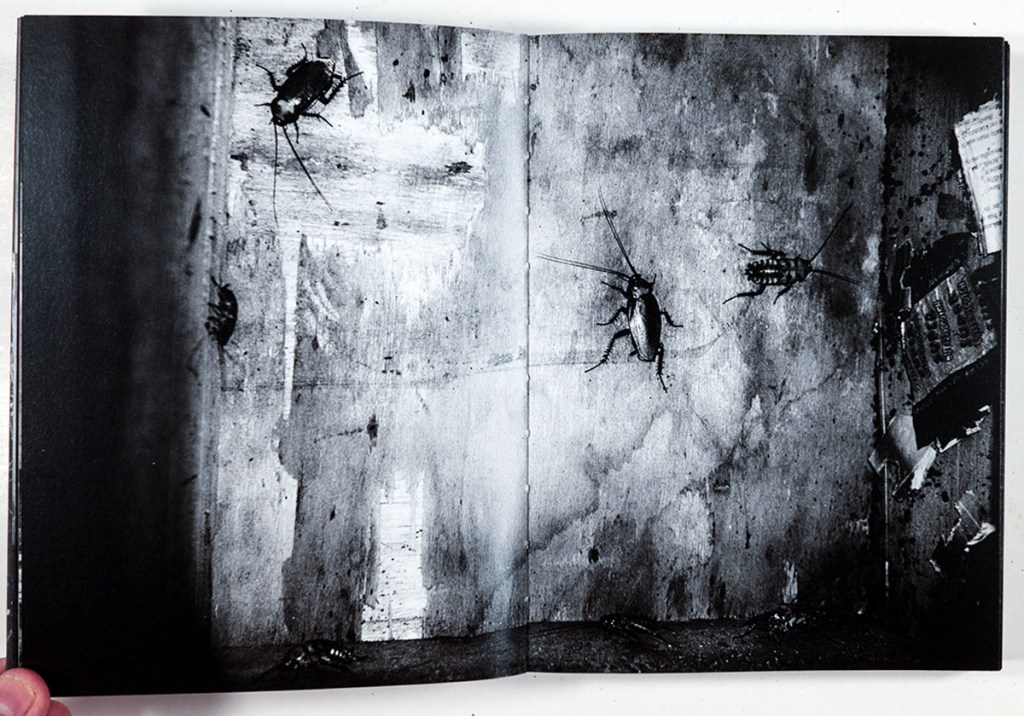

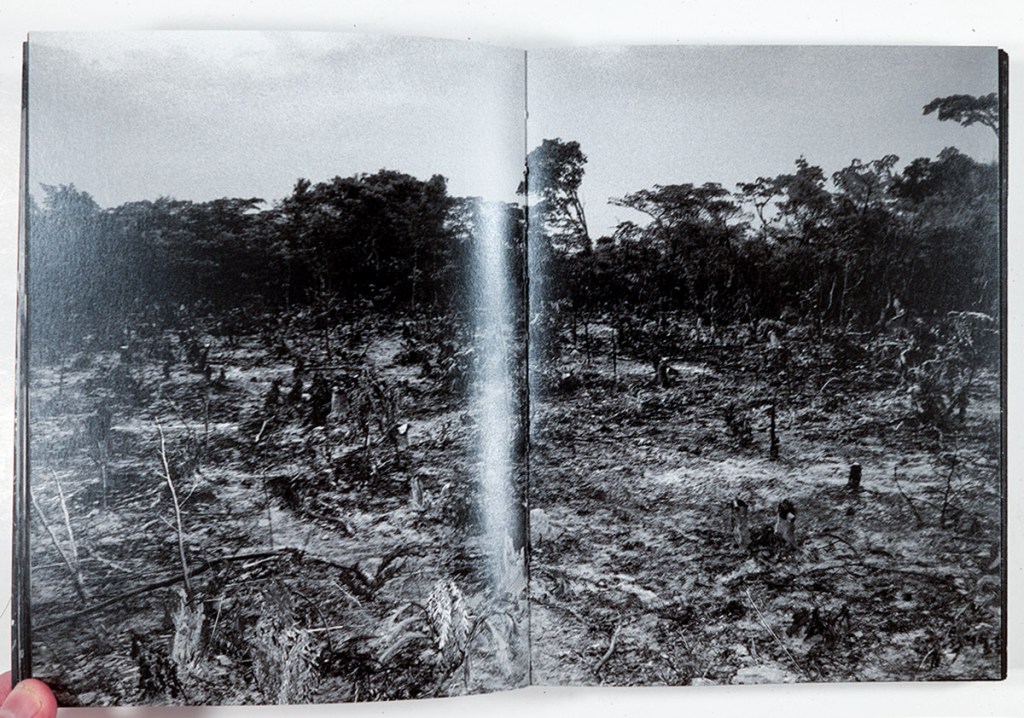

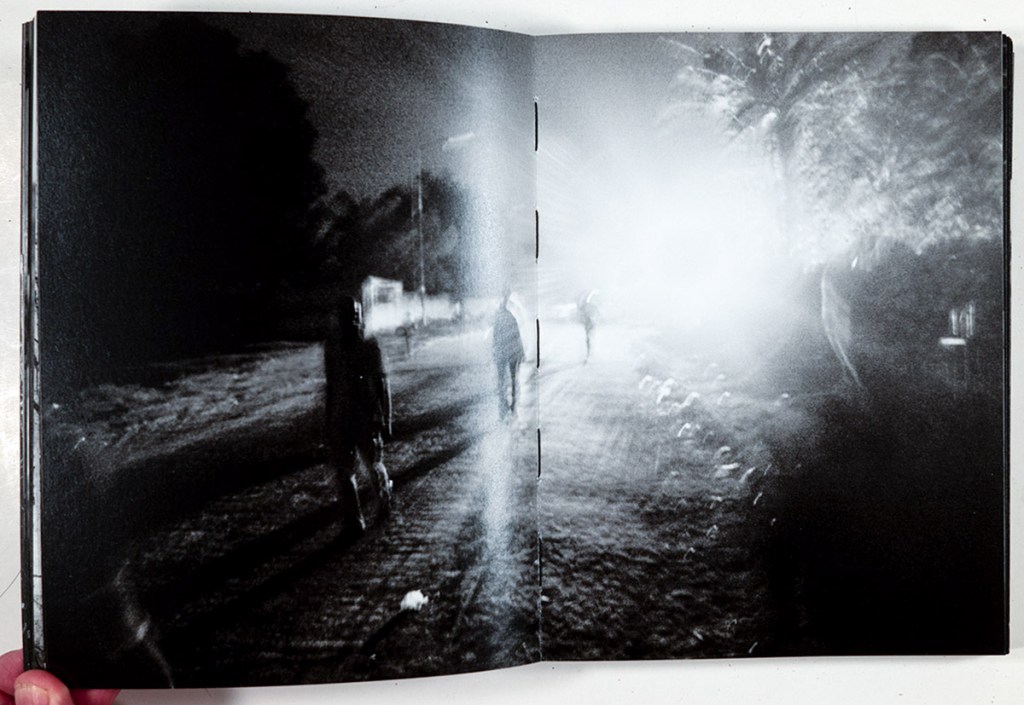

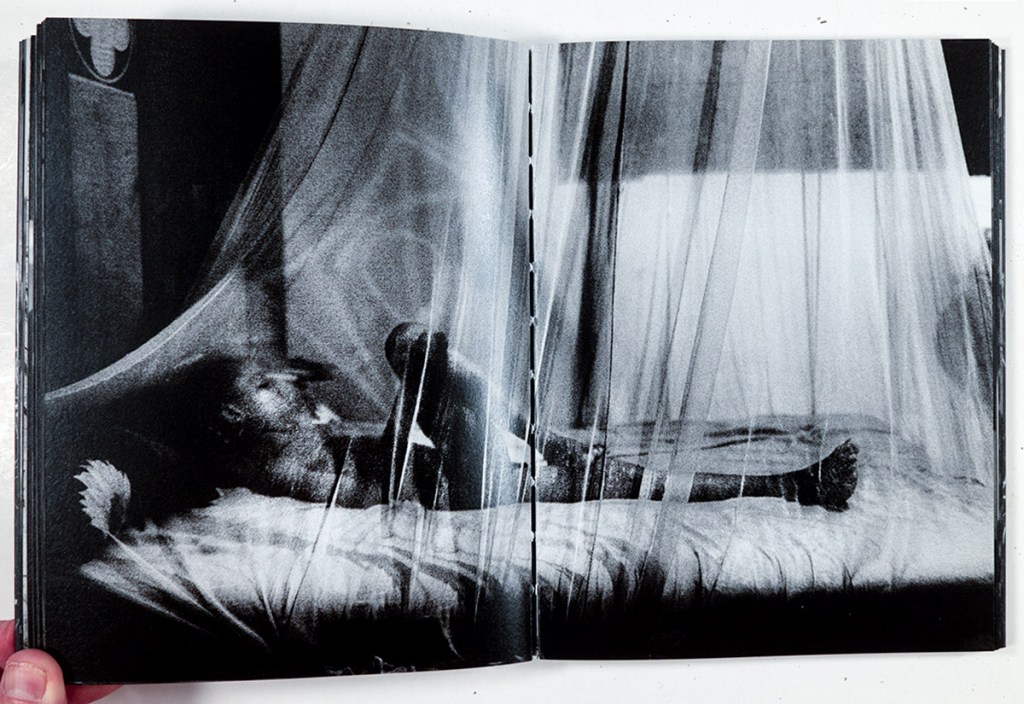

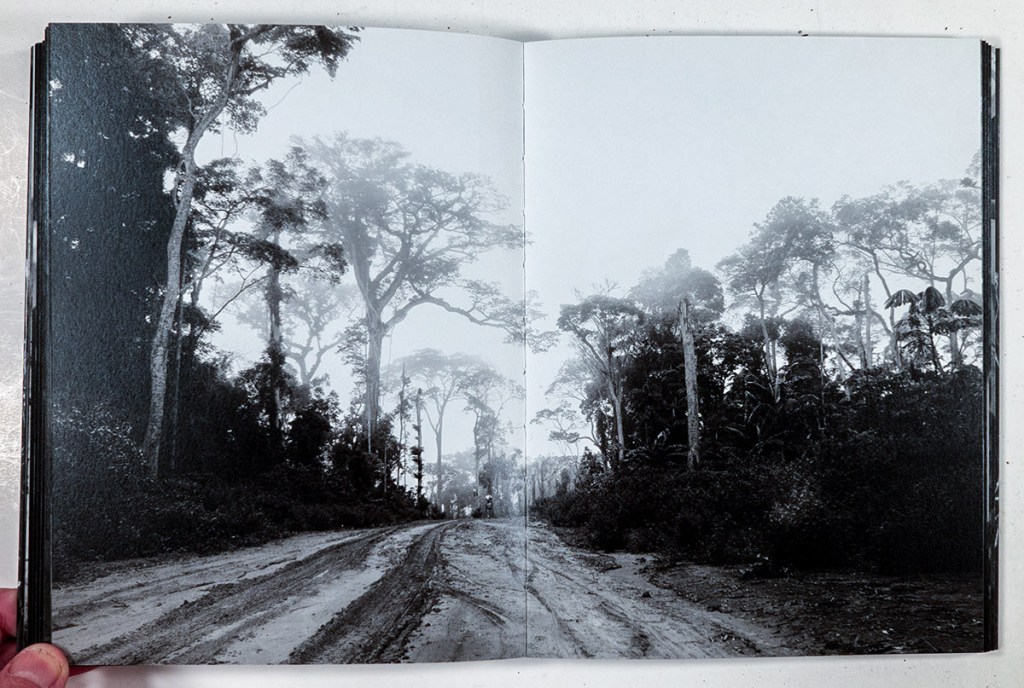

The images seem to meld together in an ambiguous and opaque darkness. This motif continues throughout the 111 images in the book, the photographs mostly being presented as either double page full bleeds or single page full bleeds. Where there are borders, they are in black. The photographs – almost all shot in dark interior spaces or at night – seem to run together to create a cryptic “dream world” of scenes and situations familiar to the participants but irrevocably strange to the viewer.

Pongo’s visual description or representation of this place is unrelenting. Mysterious spaces, often presented with enigmatic choices of focus are juxtaposed with – and often contain – moments of great emotion, sometimes between subjects and sometimes displayed by the sole figure within the frame. The images in The Uncanny are visually gripping and compelling, scenes from a narrative that seems not simply understood, but entirely strange, foreign, unheimlich. This foreignness stems partly (as mentioned above) from the darkness and opacity of the images and their presentation, but also from the resolute lack of textual information given to orient the viewer. Until we reach the critical essay by Nadia Yala Kisukidi at the end of the volume, the only language given us (other than the title) is the language displayed within the images themselves. Words on clothes, signs, banners, product wrappers, graffiti; words in French, English and, in the case of the graffiti, an unidentifiable vernacular or patois.

A consideration of the biographical information found on Pongo’s website and the publisher’s home site for this book illuminates to a certain extent the uncanniness of these photographs and this project. We find that Pongo (of Congolese heritage) was born and grew up in Belgium. The photographs herein, then, might be seen as an attempt to “return” to a place not previously lived in, a place thought of in some sense as “home,” yet anything but “homelike.” No essentialist “return” depicted here, but instead, as Freud noted, the notion of home or homelike “develops in the direction of ambivalence until it finally coincides with its opposite.” In considering the fact of Pongo, a black man of Congolese heritage being born in and growing up in Europe, specifically Belgium, I was reminded of the history and horrors of Belgian colonialism in Africa (so shatteringly described in in Sven Lindqvist’s travelog/history, Exterminate All the Brutes [1997]). And was then reminded as well of the complex and always multifaceted aspects of identity. As Edward Said writes at the conclusion of Culture and Imperialism (1994):

No one today is purely one thing. Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are not more than starting points, which if followed into actual experience for only a moment are quickly left behind.

While The Uncanny speaks powerfully as a political and geographic visual exploration and depiction of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 21st century, it speaks even more forcefully – and movingly – as a psychological journey. The complexities of what is seen and what is understood is reflected on eloquently – indeed poetically – in the concluding essay, “There are no roads. Not even a body. Nor even a glance.” writes the French philosopher Nadia Yala Kisukidi. Here, in her brief discussion of Pongo’s work, Kisukidi remarks on how these “pictures stubbornly refuse to show,” how the “photographs produce ‘something else.’ “She sees Pongo’s images as presenting the “uncanny strangeness of an intimate, familiar world which, by refusing to be named escapes…each of the images unveils its possibility as a secret.”

I find this haunting book to be one of the most powerful and challenging collections of photographs I’ve encountered in a long time. Demanding, unsettling, unrelentingly strange, we might conclude by returning (since the notion of returns is, after all, so central here) to Freud’s essay. At the conclusion of his essay, Freud suggests three factors as at the heart of the uncanny: silence, solitude and darkness. No three words better describe Pongo’s singularly powerful photographs and book.

____

Steve Harp is a Contributing Editor and Associate Professor The Art School, DePaul University

____

The Uncanny, Leonard Pongo.

Photographer: Leonard Pongo; born in Liege, Belgium and currently resides in Belgium and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Publisher: Gost Books, London, copyright 2023

Text by Nadia Yala Kisukidi.

Text: English and French.

Book description: Hardcover with clothbound cover. Printed in Italy by EBS.

Book designed and edited by GOST: Rossella Castello, Katie Clifford, Gemma Gerhard, Justine Hucker, Allon Kaye, Eleanor Macnair, Claudia Paladini, Ana Rocha.

____

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff sand the photographer(s).

Leave a comment