Copyright Rania Matar 2009 courtesy The Quantuck Lane Press

In recent years, we have become very familiar with a recent spin on combat photography; the embedded photojournalist; one who is assigned to and lives with a military unit which is in an active combat zones and is sanctioned by the military. The role and definition of the embedded photojournalist role is still familiar yet developing. Although much akin to the many war photojournalists that preceded them and who have yet to be defined by the new authority of what is; Wikipedia. I would venture that the photographic style of many embedded photojournalist begins to emote a stylistic appearance; the perspective is intimate and close, the framing is tight with the events and individuals falling out of the edges of the borders, wide-angle viewpoints in and amidst the chaos, as though afloat in the sea of combat with the action swirling about them. This too is a characterization of the photographs of Rania Matar, and the place of her project can be equal terrifying, disorienting and frightening, the places where actual combat is not yet a distant memory, amidst the immediate aftermath of war.

Regretfully, there exists many places where the aftermath of war can be found and for Matar, she has found hers in Lebanon, which also represents an emotional duality for her, that being experienced from a distance and yet in the present moment. Matar brings an ability to see the social infrastructure from an unusual perspective; she was born and raised in Lebanon and subsequently resided in the United States for over twenty-five years. She maintains the broader perspective of an outsider without appearing aloof and yet the familiarity and access of an insider. This book of black & white photographs is a result of observing, looking and watching intermittently over a five-year period, from 2003 to 2008.

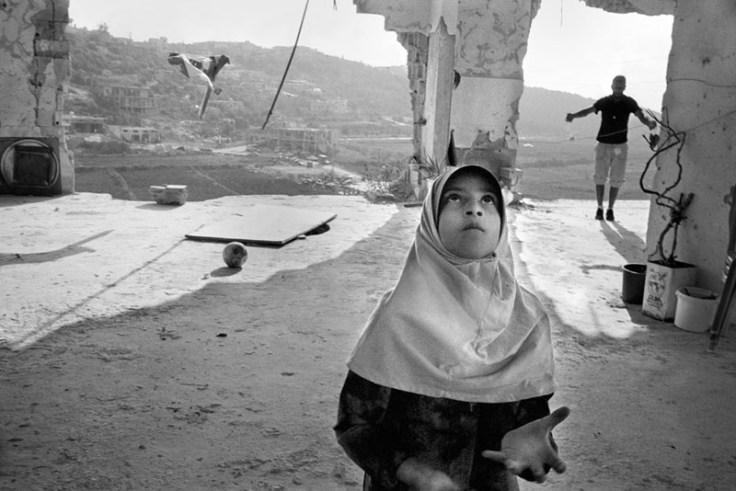

In these intimate photographs, the recent turmoil and the aftermath of internal and external war is not just a backdrop; we have been dropped into the midst of this hellish place, it surrounds and engulfs her subjects, and subsequently us, the viewer. Like war itself, many of the situations depicted is difficult to comprehend, the dichotomies are numerous and many times bordering on absurd. The social contexts are observed and recorded by Matar in a documentary style, but like a photojournalist, we also recognize that she has the ability to extract and frame events to create a visual narrative. In a heavy-handed way, this narrative could take on a strong political or religious bias, but in her narrative, it becomes apparent that her story has a sociological bias towards an attempt to investigate the social fabric of families and personal relationships coping with very difficult environmental conditions..

Many of Matar’s subjects appear to live in dismal conditions, perhaps for a short duration and other circumstances for an extended period of time, to the point that her subjects appear to be accepting the current dismal conditions as normal. We suspect that her subjects are nevertheless worldly enough to know that others beyond their sphere have a different lifestyle, as her photographs illustrate how these various social worlds collide or how they seemingly manage to co-exist. Her photographs appear to be about individuals who are searching and seeking a normalcy within the madness.

In reflecting on her work, Matar writes: “In these photographs I concentrated on people who did not lose their humanity and dignity despite what they have been and are still going through. I tried to portray them as the beautiful individuals they are, instead of as part of any religious or political group. I concentrated on the spirit with which they continue with the mundane tasks s of daily life regardless of their circumstances: their lives that are ordinary in an environment and political climate that are often anything but ordinary.”

Although the book is narrated through three sections, The Aftermath of War, The Veil: Modesty, Fashion, Devotion or Statement, and Forgotten People, her photographs appear to be equally applicable to either of these sections and it difficult for me to discern the applicability to one section from another. Her photographs seem to merge into one complex narrative. The possible exception is that the Forgotten Peopleis a story of thePalestine’s who refuge camps are in a state of “temporary” status in Lebanon for the last sixty years.

I find that Matar’s story about Lebanon has a strongly feminine undercurrent, with family relationships as the subject of her focus, and predominately the interaction of women and children, although mostly young girls. It is also a story of survival, endurance, fortitude and assimilation into the current economic and social conditions brought on by repeated conflict and segregation. Perhaps this could be construed to be a feminine response to a conflict wrought by men.

She investigates and captures the contradictions, contrast and juxtaposition of the old family and religious values with the contemporary and predominately Western lifestyles. Occasionally the photographs paired across the book’s spread are very obvious contradictions, such as the young men in bathing suits drinking at the edge of a pool, while the facing photograph contains ill-dressed children holding buckets in what appears as a food line. At other times, it may take a long time to develop an understanding of how the paired photographs complement each other. Her photographs have a warm poignancy, at time with a dry wit and humorous, and she has a watchful eye to capture the social contradictions and juxtapositions of the absurd. Thus Matar’s book can lend itself to a fast read, but I found that with investing more time, this is a visual interesting and provocative lyrical narrative.

Looking at Matar’s black & white photographs, I become aware that I am not distracted by the potential colors and hues that could overrun my senses, thus I become more attuned to of the graphic elements. Similar to her embedded photojournalist brethren, she chooses a close, tight and intimate vantage point, not poaching with a long lens, as her subjects are very aware of her presence, occasionally playing up to her. The narrative is not that of an uninterested Diane Arbus voyeur, but the visual dialog resulting from an insider’s viewpoint, sometimes gritty and difficult to view, similar to Zoe Strauss’s America.

Matar goes on to state in another one of her essays, “What struck and humbled me most was how quickly people, seasoned by the experience of war, resumed their lives, how they picked up the pieces and moved on to preserve their dignity, their children, and their spirit, with a humanity that shines through destruction and rises above the rubble.”

This hardcover book has a dust jacket and the book was printed and bound in Italy. The paper has a matte finish that subsequently reduces the contrast of the black and white interior photographs. The essays are provided by Matar and Anthony Shadid and in the accompanying end notes Matar has provided brief, yet informative, captions for each photograph.

By Douglas Stockdale

Beutiful work! You could tell that it was done by a women photographer. Very sensual, full of connotations.

Reblogueó esto en marian395's Blog.